Desvendando a Tela do Cirurgião

A Arte e a Ciência da Dissecção Abdominal

Introdução

A dissecção abdominal é a pedra angular da cirurgia digestiva, uma exploração meticulosa que revela a intrincada paisagem do abdômen humano. Para estudantes de medicina, residentes de cirurgia geral e especialistas de pós-graduação em cirurgia do sistema digestivo, dominar essa habilidade é fundamental. Este artigo mergulha nas nuances da dissecção abdominal, estabelecendo uma ponte entre o conhecimento anatômico e a perícia cirúrgica.

Importância do Tema

O abdômen, um compartimento complexo que abriga órgãos vitais, é delimitado superiormente pelo diafragma e inferiormente pela cavidade pélvica. O peritônio, uma membrana serosa, reveste essa cavidade e envolve seu conteúdo, criando um ambiente dinâmico para intervenção cirúrgica. No Brasil, as doenças do sistema digestivo representam uma parcela significativa dos procedimentos cirúrgicos. Segundo o Ministério da Saúde do Brasil, em 2022, aproximadamente 15% de todas as cirurgias realizadas no país estavam relacionadas ao sistema digestivo, ressaltando a importância da proficiência na dissecção abdominal.

O processo de dissecção abdominal começa com uma inspeção cuidadosa da cavidade. Os cirurgiões devem estar cientes de potenciais aderências, que ocorrem em quase 93% dos pacientes que passaram por cirurgias abdominais anteriores, conforme relatado pelo Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgiões. Essas aderências podem complicar a dissecção e devem ser abordadas meticulosamente. À medida que progredimos pelos quadrantes abdominais, encontramos uma variedade de órgãos, cada um com sua relação única com o peritônio. O fígado, um órgão intraperitoneal que ocupa o quadrante superior direito e se estende para o esquerdo, serve como ponto de referência para orientação. Sua posição, dividida pelo ligamento falciforme, guia a abordagem do cirurgião às estruturas circundantes.

O estômago, outro órgão intraperitoneal, situa-se predominantemente no quadrante superior esquerdo. Sua posição e relação com o omento menor são cruciais em procedimentos como gastrectomias, que representam aproximadamente 5% de todas as cirurgias digestivas no Brasil, de acordo com o Instituto Nacional de Câncer (INCA). Os intestinos delgado e grosso apresentam um arranjo complexo que exige navegação cuidadosa. As porções secundariamente retroperitoneais, como o duodeno e partes do cólon, requerem uma abordagem diferente em comparação com suas contrapartes intraperitoneais. Compreender essas relações é essencial em procedimentos como cirurgias colorretais, que constituem cerca de 8% das operações do sistema digestivo no Brasil.

Pontos-Chave:

- Relações peritoneais: Distinguir entre órgãos intraperitoneais, retroperitoneais e secundariamente retroperitoneais é crucial para o planejamento e execução cirúrgica.

- Marcos anatômicos: Utilizar estruturas como o ligamento falciforme e inserções omentais auxilia na orientação e dissecção.

- Considerações vasculares: A consciência dos principais vasos e seus trajetos é vital para prevenir lesões iatrogênicas durante a dissecção.

- Contexto embriológico: Compreender a anatomia do desenvolvimento ajuda a entender reflexões peritoneais complexas e inserções ligamentares.

- Implicações patológicas: Reconhecer como as patologias alteram a anatomia normal é essencial para uma dissecção segura e eficaz.

Conclusões Aplicadas à Prática da Cirurgia Digestiva

O domínio da dissecção abdominal se traduz diretamente em melhores resultados cirúrgicos. Em procedimentos laparoscópicos, que agora representam mais de 60% das cirurgias abdominais nos hospitais terciários do Brasil, uma compreensão profunda das relações tridimensionais é indispensável. A capacidade de navegar pelas reflexões peritoneais e identificar estruturas-chave através de pontos de acesso mínimos depende fortemente do conhecimento fundamental adquirido através de técnicas de dissecção aberta. Além disso, em ressecções oncológicas complexas, onde a linfadenectomia radical é frequentemente necessária, o conhecimento íntimo do cirurgião sobre os espaços retroperitoneais e seus conteúdos pode significar a diferença entre resultados curativos e paliativos. Com o câncer gástrico sendo a terceira malignidade mais comum do sistema digestivo no Brasil, afetando aproximadamente 21.000 indivíduos anualmente, a importância da dissecção precisa não pode ser subestimada.

Em conclusão, a dissecção abdominal não é meramente uma habilidade técnica, mas uma forma de arte que requer refinamento constante. À medida que avançamos em técnicas minimamente invasivas e cirurgias robóticas, a base estabelecida pelos métodos tradicionais de dissecção permanece inestimável. O cirurgião que domina essa arte está bem equipado para enfrentar os desafios da cirurgia digestiva moderna, melhorando os resultados dos pacientes e avançando o campo.

Como disse o renomado cirurgião William Stewart Halsted: “A aquisição de habilidade técnica em cirurgia é diferente de qualquer outro campo profissional, pois trata constantemente de uma anatomia humana singular.”

DissecçãoAbdominal #CirurgiaDigestiva #AnatomiaCircúrgica #EducaçãoMédica #SaúdeBrasileira

Gostou? Deixe-nos um comentário ✍️, compartilhe em suas redes sociais e|ou envie sua pergunta via 💬 Chat Online em nossa DM do Instagram.

Prevention of Bile Duct Injury

Prevention of Bile Duct Injury During Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Introduction

Bile duct injury (BDI) during laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a significant surgical complication with profound clinical and medico-legal implications. The incidence of BDI ranges from 0.3% to 0.6%, despite advances in surgical techniques and imaging modalities. The prevalence of BDI remains concerning due to its association with high morbidity and mortality rates. Patients who suffer from BDI often face prolonged hospital stays, multiple surgeries, and long-term complications such as bile leakage, strictures, and secondary biliary cirrhosis. Medico-legally, BDI is one of the most common reasons for litigation against surgeons, often resulting in significant financial settlements and professional repercussions.

Questions and Answers

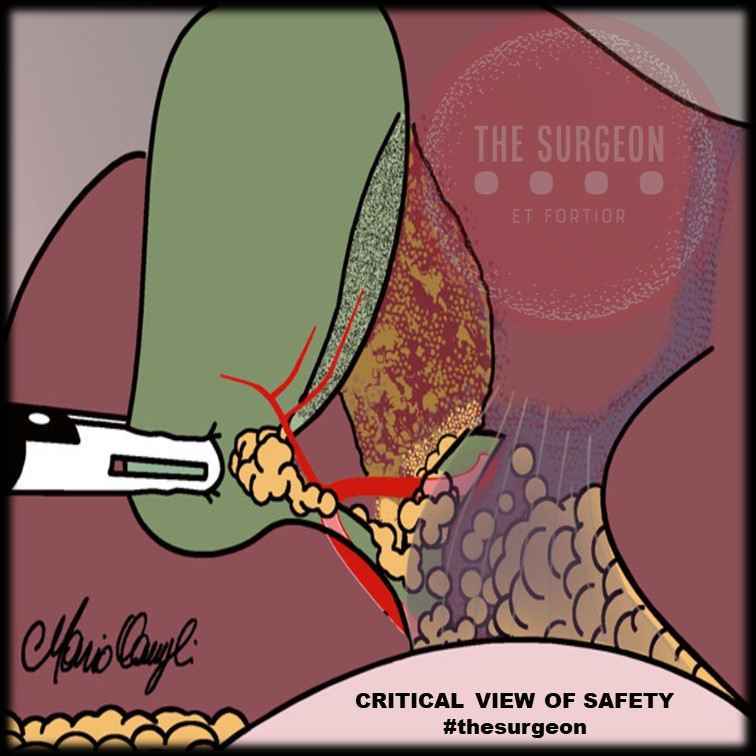

Question 1: What technique should be used to identify the anatomy during laparoscopic cholecystectomy?

Answer: The Critical View of Safety (CVS) is recommended for identifying the cystic duct and cystic artery.

Key Findings: The incidence of BDI was found to be 2 in one million cases using CVS, compared to 1.5 per 1000 cases with the infundibular technique.

Question 2: When should intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) be used?

Answer: IOC should be used in cases of anatomical uncertainty or suspicion of bile duct injury.

Key Findings: IOC aids in the prevention and immediate management of BDI by providing a precise assessment of biliary anatomy during surgery.

Question 3: What are the recommendations for managing patients with confirmed or suspected bile duct injury?

Answer: Patients with confirmed or suspected BDI should be referred to an experienced surgeon or a multidisciplinary hepatobiliary team.

Key Findings: Early referral to hepatobiliary specialists is associated with better long-term outcomes and lower complication rates.

Question 4: Should the “fundus-first” technique be used when CVS cannot be achieved?

Answer: Yes, the “fundus-first” technique is recommended when CVS cannot be achieved.

Key Findings: This technique is effective for safely dissecting the gallbladder in complex cases where anatomy is unclear.

Question 5: Should CVS be documented during laparoscopic cholecystectomy?

Answer: Yes, documenting CVS with double-static photographs is recommended.

Key Findings: Photographic documentation of CVS ensures correct anatomical identification and serves as a record for later review in case of complications.

Question 6: Should near-infrared biliary imaging be used intraoperatively?

Answer: The evidence for near-infrared biliary imaging is limited; thus, IOC is preferred.

Key Findings: IOC is more widely studied and proven effective in preventing BDI compared to near-infrared imaging.

Question 7: Should surgical risk stratification be used to mitigate the risk of BDI?

Answer: Yes, surgical risk stratification is recommended.

Key Findings: Risk stratification helps identify patients at higher risk of complications, aiding in surgical planning and decision-making.

Question 8: Should the presence of cholecystolithiasis be considered in risk stratification?

Answer: Yes, the presence of cholecystolithiasis should be considered in risk stratification.

Key Findings: Patients with cholecystolithiasis have a higher risk of complications during cholecystectomy, making it important to include this condition in risk assessments.

Question 9: Should immediate cholecystectomy be performed in cases of acute cholecystitis?

Answer: Yes, immediate cholecystectomy within 72 hours is recommended.

Key Findings: Surgery within 72 hours of the onset of acute cholecystitis symptoms is associated with lower complication rates and better patient recovery.

Question 10: Should subtotal cholecystectomy be performed in cases of severe inflammation?

Answer: Yes, subtotal cholecystectomy is recommended in cases of severe inflammation where CVS cannot be obtained.

Key Findings: In severe inflammation scenarios, subtotal cholecystectomy can facilitate the surgery and reduce the risk of BDI.

Question 11: Which approach is preferable, four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy or reduced-port/single-incision?

Answer: Four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy is recommended as the standard approach.

Key Findings: The four-port technique is the most studied, showing effectiveness and safety in performing cholecystectomies with lower complication risks.

Question 12: Should interval cholecystectomy be performed following percutaneous cholecystostomy?

Answer: Yes, interval cholecystectomy is recommended after initial stabilization with percutaneous cholecystostomy.

Key Findings: Interval cholecystectomy offers better long-term outcomes and lower risk of recurrent complications compared to no additional treatment.

Question 13: Should laparoscopic cholecystectomy be converted to open in difficult cases?

Answer: Yes, conversion to open surgery is recommended in cases of significant difficulty.

Key Findings: Conversion to open surgery can prevent BDI in situations where laparoscopic dissection is extremely difficult or risky.

Question 14: Should a waiting time be implemented to verify CVS?

Answer: Yes, a waiting time to verify CVS is recommended.

Key Findings: A waiting time allows better anatomical evaluation before proceeding with dissection, reducing the risk of BDI.

Question 15: Should two surgeons be used in complex cases?

Answer: The presence of two surgeons can be beneficial in complex cases, although strong recommendations are not made due to limited evidence.

Key Findings: Some studies suggest that collaboration between two surgeons can improve anatomical identification and reduce complications in difficult cases.

Question 16: Should surgeons receive coaching on CVS to limit the risk or severity of BDI?

Answer: Yes, surgeons should receive coaching on CVS.

Key Findings: Surgeons who receive targeted coaching on CVS show improved anatomical identification and reduced rates of BDI.

Question 17: Should simulation or video-based education be used to train surgeons?

Answer: Yes, simulation or video-based education should be used.

Key Findings: These training methods enhance technical skills, increase surgical precision, and reduce the incidence of BDI during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Conclusion

The consensus recommendations provide evidence-based approaches to minimize bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Practices such as the critical view of safety (CVS), intraoperative cholangiography (IOC), and early referral to specialists can significantly improve surgical outcomes and reduce complications. As famously stated, “The history of surgery is the history of the control of bleeding,” a phrase that underscores the importance of meticulous surgical technique and the prevention of complications like bile duct injuries.

Gastrointestinal Anastomosis

Navigating the Gastrointestinal Anastomosis: A Surgical Odyssey

Unveiling the Historical Tapestry 🕰️

The creation of gastrointestinal anastomoses, an art in general surgery, has evolved over centuries. In delving into this surgical saga, fundamental principles stand tall, guiding the surgeon’s hands. This chapter unfolds the historical nuances, general tenets for successful anastomosis creation, and delves into pivotal technical considerations amidst current controversies.

The Dance of Healing and Anatomy 🩹🔍

Understanding the physiological waltz of gastrointestinal wound healing and the intricacies of intestinal wall anatomy sets the stage. An enterotomy’s inception triggers a symphony of vasoconstriction, vasodilation, and capillary changes, orchestrating the ballet of tissue healing. Granulation tissue emerges, heralding the proliferative phase, where collagen undergoes a dance of lysis and synthesis.

Layers of the Gastrointestinal Tapestry 🧵

The intestinal wall, a multilayered tapestry, unravels its secrets. The serosa, a connective tissue cloak veiled by mesothelial lining, demands precise apposition to thwart leakage risks. The submucosa, the stronghold of tensile strength, anchors the sutures knitting the anastomosis. Intestinal mucosa seals the deal, driven by epithelial cell migration and hyperplasia, crafting a watertight barrier.

Local Factors: Paving the Path to Healing ⚒️🩹

The local factors influencing this symphony include intrinsic blood supply and tension management. Adequate blood supply, a lifeline for tissue oxygenation, hinges on meticulous surgical technique. Tension, a delicate partner in this dance, demands finesse; too much jeopardizes perfusion, too little invites inflammatory infiltrates. The colon, in particular, demands a surgeon’s nuanced touch.

Systemic Harmony: The Ripples of Patient Factors 🔄🌊

Systemic factors contribute their ripples to this surgical pond. Hypotension, hypovolemia, and sepsis compose a dissonant note affecting blood flow and oxygen delivery. Patient-specific variables — malnutrition, immunosuppression, and medication use (hello, steroids and NSAIDs) — compose a subplot, influencing the narrative of wound healing.

As the surgeon steps into this intricate ballet of anastomosis creation, history, physiology, and patient-specific factors converge. Each suture, each decision, shapes the narrative of healing. The gastrointestinal odyssey continues, blending tradition with innovation, as surgeons embark on the timeless quest for successful anastomoses. 🌐🔍🩺

Tubes and Drains

Unlocking the World of Tubes and Drains in Medical Practice 🩹

Understanding the diverse array of tubes and drains is crucial for any medical practitioner, and it all begins with appreciating the French size system, where the outer diameter of a catheter is denoted. A quick calculation (French size multiplied by 0.33) reveals the catheter’s outer diameter in millimeters.

Gastrointestinal Tract Tubes 🍽️

Starting with nasogastric tubes designed to evacuate gastric contents, these are frequently employed in patients facing ileus or obstruction. Modern nasogastric tubes often incorporate a sump function, preventing suction locks and enhancing efficiency. Nonsump tubes, though less common, may be used for intermittent suction. Nasogastric tubes also serve in feeding, with soft, fine-bore tubes being preferred for this purpose. Nasoenteric tubes, intended for feeding, require careful attention to safety during instillation.

Nasobiliary tubes, often placed endoscopically, aid in biliary drainage in cases of obstruction or fistula. T-tubes within the common bile duct ensure closed gravity drainage. Gastrostomy tubes, placed surgically or via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), find utility in drainage or feeding. Jejunostomy tubes, inserted surgically or endoscopically, are vital for long-term nutritional access.

Respiratory Tract Tubes 🫁

Chest tubes play a pivotal role in pleural cavity drainage, addressing issues like pneumothorax, hemothorax, or effusion. The three-bottle system facilitates constant suction, drainage, and prevention of air entry, crucial for maintaining a water seal.

Endotracheal tubes, cuffed for a secure tracheal seal, cater to short-term mechanical ventilation needs in adults. Tracheotomy tubes, directly inserted into the trachea through the neck, become essential for prolonged mechanical ventilation or when maintaining a patent airway is challenging.

Urinary Tract Tubes 🚰

Bladder catheters, commonly known as “Foley” catheters, serve to straight drain urine. Nephrostomy tubes, placed in the renal pelvis, drain urine above obstructions or delicate ureteral anastomoses. Percutaneously placed tubes, often pigtail catheters, assist in draining abscesses, typically guided by interventional radiologists.

Surgical Drains 🌡️

Closed suction drains, such as Jackson-Pratt and Hemovac, prove invaluable for evacuating fluid collections during surgery. Sump suction drains, like Davol drains, are larger and designed for continuous suction in scenarios with thick or particulate drainage. Passive tubes, exemplified by Penrose drains, offer a pathway for fluid without applied suction, serving as a two-way conduit for bacteria. Understanding these various tubes and drains is pivotal for medical practitioners navigating complex clinical scenarios. 💉💊

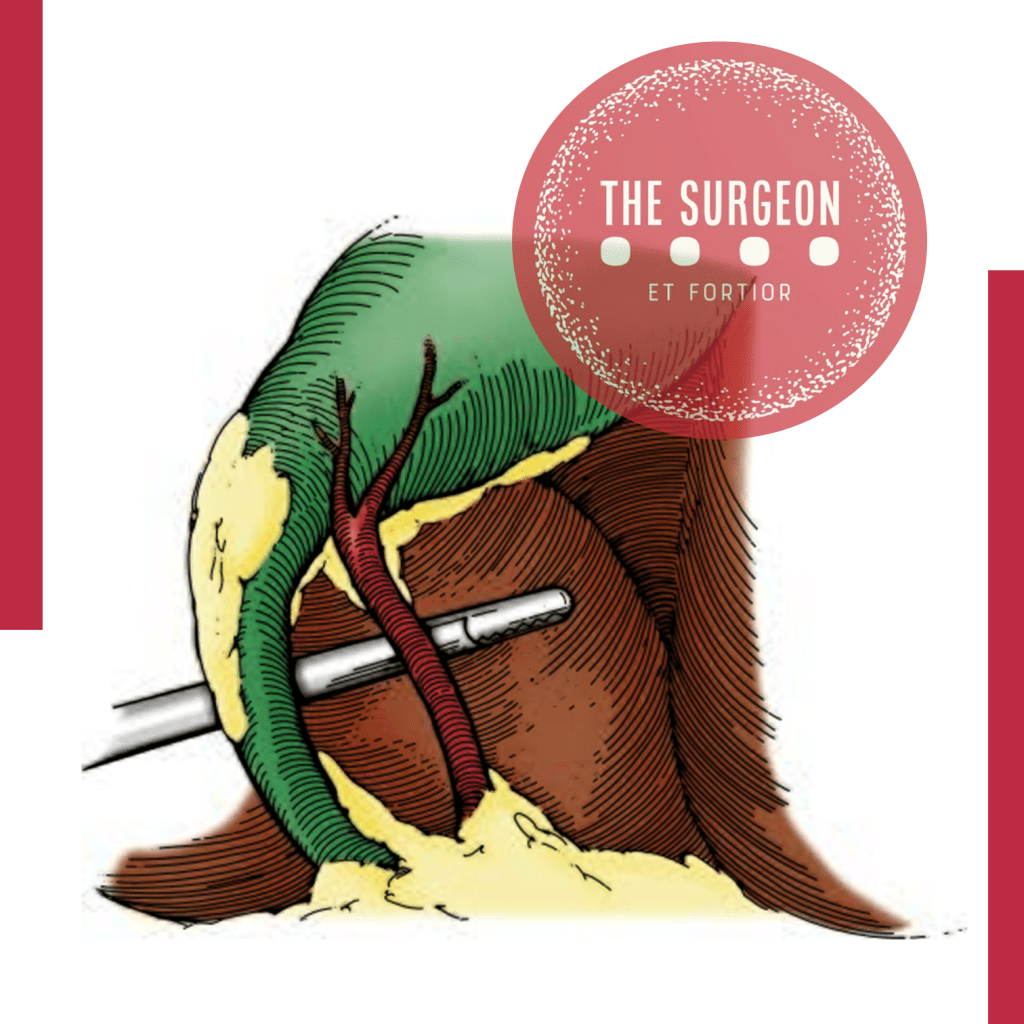

10 Anatomical Aspects for Prevention the Bile Duct Injury

Essential aspects to visualize and interpret the anatomy during a cholecystectomy:

1. Have the necessary instruments for the procedure, with adequate positioning of the trocars and a 30-degree optic.

2. Cephalic traction of the gallbladder fundus and lateral traction (pointing to the patient’s right shoulder), to reduce redundancy of the infundibulum.

3. Puncture and evacuation of the gallbladder to improve its retraction, in cases where traction cannot be performed easily (acute cholecystitis).

4. Lateral and caudal traction of the infundibulum, for correct exposure of Calot’s triangle, exposing the CD and artery.

5. “Critical view of Safety” to avoid misidentification of the bile ducts, ensuring that only two structures (CD and artery) are attached to the gallbladder. For this, they must be dissected separately, and the proximal third of the gallbladder must be moved from its fossa, to ensure that there is no anatomical variant there.

6. Systematic use of intraoperative cholangiography. Ideally by transcystic route or possibly by a puncture of the gallbladder.

7. Ligation of the cystic duct with knots (“endoloop”) to prevent migration of metallic clips that could condition a postoperative leak.

8. In case of severe inflammation of the gallbladder pedicle, with its retraction or lack of recognition of cystic structures, a subtotal cholecystectomy might be indicated.

9. In case of hemorrhage, avoid indiscriminate clip placement and or blind cautery. Opt for compressive maneuvers and, once the bleeding site has been identified, evaluate the best method of hemostasis.

10. If the surgeon is not able to resolve the injury caused, it is always better to ask for help from a colleague, and if necessary, to refer the patient to a specialized center.

#SafetyFirst

The main goal in the postoperative management of BDI is to control sepsis in the first instance and to convert an uncontrolled biliary leak into a controlled external biliary fistula to achieve optimal local and systemic control. Definitive treatment to re-establish biliary continuity will be deferred once this primary goal is achieved and should not be obsessively pursued in the acute phase. The factors that will determine the initial presentation of a patient with a BDI in the postoperative stage are related to the time elapsed since the primary surgery, the type of injury, the mechanism of injury, and the overall general condition of the patient.

Anatomia Cirúrgica da REGIÃO INGUINAL

A hérnia inguinal é uma condição comum que ocorre quando um órgão abdominal protraí através de uma fraqueza na parede abdominal na região abdominal. O orifício miopectineal é a principal área de fraqueza na parede abdominal onde a hérnia inguinal pode se desenvolver. O conhecimento da anatomia da parede abdominal é importante para entender a patofisiologia da hérnia inguinal e para ajudar no diagnóstico e tratamento dessa condição médica comum.

Visão Crítica de Segurança (Colecistectomia)

A colecistectomia laparoscópica (CL) é o padrão-ouro para tratamento de cálculos biliares. No entanto, o risco de lesão do ducto biliar (BDI) continua a ser preocupação significativa, uma vez que CL ainda tem taxa de BDI maior do que a via laparotômica, apesar de muitos esforços propostos para aumentar sua segurança.

A Visão Crítica da Segurança (CVS) proposta por Strasberg é a técnica para a identificação dos elementos críticos do triângulo de Calot durante a CL. Esta técnica foi adotada em vários programas de ensino e com a proposta de reduzir o risco de BDI e o uso da adequado da CVS está associado a menores taxas de BDI. O objetivo deste #Webinar é abordar a Anatomia Cirúrgica Fundamental para a realização de uma Colecistectomia Laparoscópica.

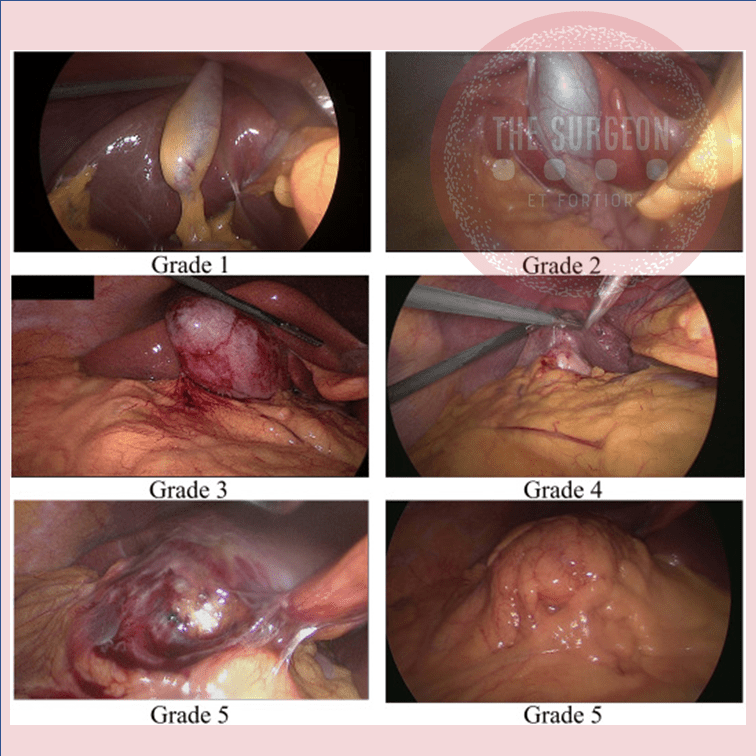

The “BAD” Gallbladder

Once the decision for surgery has been made, an operative plan needs to be discussed and implemented. Should one initially start with laparoscopic surgery for the “bad gallbladder”? If a laparoscopic approach is taken, when should bail-out maneuvers be attempted? Is converting to open operation still the standard next step? A 2016 study published by Ashfaq and colleagues sheds some light on our first question. They studied 2212 patients who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy, of which 351 were considered “difficult gallbladders.” A difficult gallbladder was considered one that was necrotic or gangrenous, involved Mirizzi syndrome, had extensive adhesions, was converted to open, lasted more than 120 minutes, had a prior tube cholecystostomy, or had known gallbladder perforation. Seventy of these 351 operations were converted to open. The indications for conversion included severe inflammation and adhesions around the gallbladder rendering dissection of triangle of Calot difficult (n 5 37 [11.1%]), altered anatomy (n 5 14 [4.2%]), and intraoperative bleeding that was difficult to control laparoscopically (n 5 6 [1.8%]). The remaining 13 patients (18.5%) included a combination of cholecystoenteric fistula, concern for malignancy, common bile duct exploration for stones, and inadvertent enterotomy requiring small bowel repair. Comparing the total laparoscopic cholecystectomy group and the conversion groups, operative time and length of hospital stay were significantly different; 147 +- 47 minutes versus 185 +- 71 minutes (P<.005) and 3+-2 days versus 5+-3 days (P 5 .011), respectively. There was no significant difference in postoperative hemorrhage, subhepatic collection, cystic duct leak, wound infection, reoperation, and 30-day mortality.2 From these findings, we can glean that most cholecystectomies should be started laparoscopically, because it is safe to do so. It is the authors’ practice to start laparoscopically in all cases.

BAILOUT PROCEDURES

Despite the best efforts of experienced surgeons, it is sometimes impossible to safely obtain the critical view of safety in a bad gallbladder with dense inflammation and even scarring in the hepatocystic triangle. Continued attempts to dissect in this hazardous region can lead to devastating injury, including transection of 1 or both hepatic ducts, the common bile duct, and/or a major vascular injury (usually the right hepatic artery). Therefore, it is imperative that any surgeon faced with a bad gallbladder have a toolkit of procedures to safely terminate the operation while obtaining maximum symptom and source control, rather than continue to plunge blindly into treacherous terrain. If the critical view of safety cannot be achieved owing to inflammation, and when further dissection in the hepatocystic triangle is dangerous, these authors default to laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy as our bail-out procedure of choice. The rationale for this approach is that it resolves symptoms by removing the majority of the gallbladder, leading to low (although not zero) rates of recurrent symptoms. It is safe, and can be easily completed laparoscopically, thus avoiding the longer hospital stay and morbidity of an open operation. There is now significant data supporting this approach. In a series of 168 patients (of whom 153 were laparoscopic) who underwent subtotal cholecystectomy for bad gallbladders, the mean operative time was 150 minutes (range, 70–315 minutes) and the average blood loss was 170 mL (range, 50–1500 mL). The median length of stay for these patients was 4 days (range, 1–68 days), and there were no common bile duct injuries.23 There were 12 postoperative collections (7.1%), 4 wound infections (2.4%), 1 bile leak (0.6%), and 7 retained stones (4.2%), but the 30-day mortality was similar to those who underwent a total laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Elshaer and colleagues showed that subtotal cholecystectomy achieves comparable morbidity rates compared with total cholecystectomy. These data support the idea that we should move away from the idea that the only acceptable outcome for a cholecystectomy is the complete removal of a gallbladder, especially when it is not safe to do so. This shift toward subtotal cholecystectomy has been appropriately referred to as the safety first, total cholecystectomy second approach.

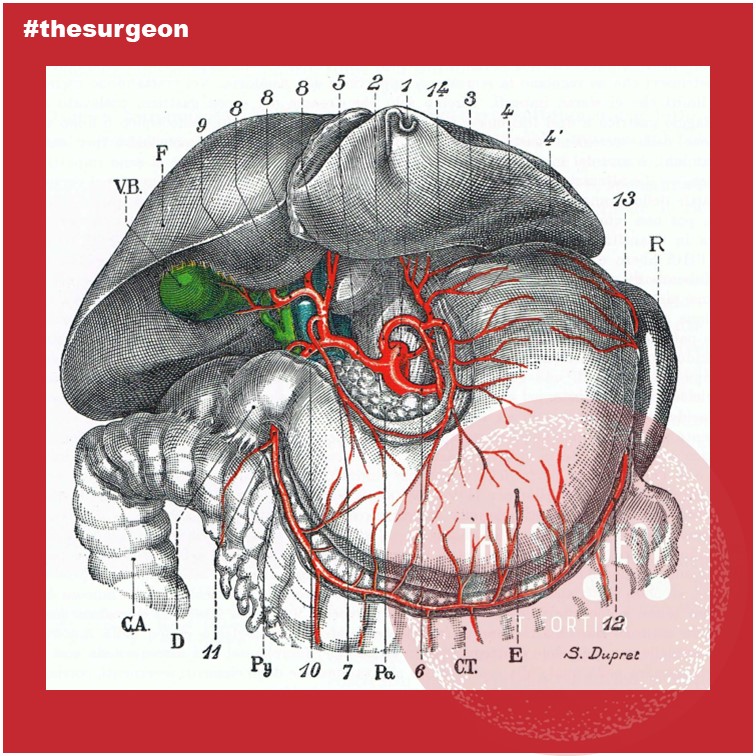

Biliary Tree Vascularization

The gallbladder lies at the equator between the right and left hemiliver, an imaginary line known as Cantlie’s line or the Rex-Cantlie line coursing between segments 4b and 5, through the bed of the gallbladder towards the vena cava posteriorly. The gallbladder is mostly peritonealized, except for its posterior surface which lies on the cystic plate, a fibrous area on the underside of the liver.

The proportion if its circumference varies, from a pedicled gallbladder with little to no contact with the cystic plate to a mostly intrahepatic gallbladder surrounded by liver parenchyma. The gallbladder carries no muscularis mucosa, no submucosa, and a discontinuous muscularis and only carries a serosa on the visceral peritonealized surface. These anatomical specificities facilitate the direct invasion of gallbladder cancer into the liver. This is why the surgical treatment of gallbladder cancer mandates a radical cholecystectomy, which includes resection of a wedge of segments 4b and 5, when the T stage is higher or equal to T1b. From the body of the gallbladder, a conical infundibulum becomes a cystic duct that extends as the lower edge of the hepatocystic triangle towards the porta hepatis and joins with the common hepatic duct (CHD) to form the CBD. As in the rest of the biliary system, variation is the rule when it comes to the cystic duct confluence with the CHD. It can variably run parallel to it for a distance prior to inserting or spiral behind it and insert on its medial aspect. It can variably insert into the RHD or the RPD, the latter in 4% of livers and particularly when the RPD inserts into the CHD (i.e., below the left-right ductal confluence). This configuration is notorious for exposing the RPD to a risk of injury at the time of cholecystectomy. Rare variations of gallbladder anatomy, including gallbladder duplication and gallbladder agenesis, are also described but are rare. The CBD courses anterolaterally within the hepatoduodenal ligament, usually to the right of the hepatic artery and anterolaterally to the portal vein. However, hepatic arterial anatomy can vary, and when an accessory or replaced hepatic artery is present arising from the superior mesenteric artery, the accessory or replaced vessel courses lateral to the CBD. In its conventional configuration, the right hepatic artery crosses posteriorly to the RHD as it heads towards the right liver, but 25% of the time it crosses anteriorly. These anatomical variants are all relevant to developing a sound surgical strategy to treat hilar CCA. Of note, while left hepatic artery anatomy can also be quite variable, rarely does it affect surgical decision-making in CCA to the same degree as right hepatic artery anatomy.

Distally, the CBD enters the head of the pancreas, joining the pancreatic duct to form the hepatopancreatic ampulla. Just distal to this is the sphincter of Oddi, which controls emptying of ampullary contents into the second portion of the duodenum. When the junction of the CBD and the pancreatic duct occurs before the sphincter complex, reflux of pancreatic enzymes into the biliary tree can lead to chronic inflammatory changes and anatomical distortion resulting in choledochal cysts, known risk factors for the development of CCA. Unlike the rest of the liver parenchyma, which receives dual supply from the arterial and portal venous circulation, the biliary tree is exclusively alimented by the arterial system. The LHD and RHD are alimented respectively by the left hepatic artery and right hepatic artery, which can frequently display replaced, accessory, and aberrant origins – the left artery arising conventionally from the hepatic artery proper but alternatively from the left gastric artery and the right hepatic artery arising from the hepatic artery proper but also variably from the superior mesenteric artery. In hilar CCA, variable combinations of hepatic arterial anatomy and tumor location can either favor resectability or make a tumor unresectable.

Within the hilum of the liver, a plexus of arteries connects the right and left hepatic arteries. Termed the “hilar epicholedochal plexus,” this vascular network provides collateral circulation that can maintain arterial supply to one side of the liver if the ipsilateral vessel is damaged. The preservation of arterial blood supply to the liver remnant is crucial, particularly when creating an enterobiliary anastomosis. Its absence leads to ischemic cholangiopathy and liver abscesses that can be difficult to treat. The CBD receives arterial supply inferiorly from paired arterioles arising from the gastroduodenal artery and the posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, the most important and constant arterial supply to the distal CBD. Proximally the CBD is alimented by paired arterioles of the right hepatic artery. These vessels, known as the marginal arteries, run in parallel to the CBD, laterally and medially to it. Denuding the CBD of this arterial supply risks stricture formation after choledochoenteric anastomosis.

#OzimoGama #TheSurgeon #DigestiveSurgery

References : https://bit.ly/3fOmcv2

Hepatocellular ADENOMA

Benign liver tumours are common and are frequently found coincidentally. Most benign liver lesions are asymptomatic, although larger lesions can cause non-specific complaints such as vague abdominal pain. Although rare, some of the benign lesions, e.g. large hepatic adenomas, can cause complications such as rupture or bleeding. Asymptomatic lesions are often managed conservatively by observation. Surgical resection can be performed for symptomatic lesions or when there is a risk of malignant transformation. The type of resection is variable, from small, simple, peripheral resections or enucleations, to large resections or even liver transplantation for severe polycystic liver disease.

General Considerations

Hepatocellular adenomas (HCA) are rare benign hepatic neoplasms in otherwise normal livers with a prevalence of around 0.04% on abdominal imaging. HCAs are predominantly found in women of child-bearing age (2nd to 4th decade) with a history of oral contraceptive use; they occur less frequently in men. The association between oral contraceptive usage and HCA is strong and the risk for a HCA increases if an oral contraceptive with high hormonal potency is used, and if it is used for over 20 months. Long-term users of oral contraceptives have an estimated annual incidence of HCA of 3–4 per 100000. More recently, an increase in incidence in men has been reported, probably related to the increase in obesity, which is reported as another risk factor for developing HCA. In addition, anabolic steroid usage by body builders and metabolic disorders such as diabetes mellitus or glycogen storage disease type I are associated with HCAs. HCAs in men are generally smaller but have a higher risk of developing into a malignancy. In the majority of patients, only one HCA is found, but in a minority of patients more than 10 lesions have been described (also referred to as liver adenomatosis).

Clinical presentation

Small HCAs are often asymptomatic and found on abdominal imaging being undertaken for other purposes, during abdominal surgery or at autopsy. Some patients present with abdominal discomfort, fullness or (right upper quadrant) pain due to an abdominal mass. It is not uncommon that the initial symptoms of a HCA are acute onset of abdominal pain and hypovolaemic shock due to intraperitoneal rupture. In a series of patients who underwent resection, bleeding was reported in up to 25%. The risk of rupture is related to the size of the adenoma. Exophytic lesions (protruding from the liver) have a higher chance of bleeding compared to intrahepatic or subcapsular lesions (67% vs 11% and 19%, respectively, P<0.001). Lesions in segments II and III are also at higher risk of bleeding compared to lesions in the right liver (35% vs 19%, P = 0.049).

Management

There is no guideline for the treatment of HCAs, although there are general agreements. In men, all lesions should be considered for surgical resection independent of size, given the high risk of malignant transformation, while taking into account comorbidity and location of the lesion. Resection should also be considered in patients with HCAs due to a metabolic disorder. In women, lesions <5 cm can be observed with sequential imaging after cessation of oral contraceptive treatment. In larger tumours, treatment strategies vary. Some clinicians have proposed non-surgical management if hormone therapy is stopped and patients are followed up with serial radiological examinations. The time period of waiting is still under debate, however recent studies indicate that a waiting period of longer than 6 months could be justified.

More recently, the subtypes of the Bordeaux classification of HCA have been studied related to their risk of complications. Some groups report that percutaneous core needle biopsy is of limited value because the therapeutic strategy is based primarily on patient sex and tumour size. Others report a different therapeutic approach based on subtype. Thomeer et al. concluded that there was no evidence to support the use of subtype classification in the stratification and management of individual patients related to risk of bleeding. Size still remains the most important feature to predict those at risk of bleeding during follow-up. However, malignant transformation does seem to be related to differences in subtypes. β-catenin-mutated HCAs trigger a potent mitogenic signalling pathway that is prominent in HCC. Cases of inflammatory HCAs can also show activation of the β-catenin pathway with a risk of developing malignancy. Therefore, β-catenin-mutated and inflammatory HCAs are prone to malignant degeneration, and particularly if >5cm. In these circumstances, invasive treatment should be considered.

Critical View Of Safety

“The concept of the critical view was described in 1992 but the term CVS was introduced in 1995 in an analytical review of the emerging problem of biliary injury in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. CVS was conceived not as a way to do laparoscopic cholecystectomy but as a way to avoid biliary injury. To achieve this, what was needed was a secure method of identifying the two tubular structures that are divided in a cholecystectomy, i.e., the cystic duct and the cystic artery. CVS is an adoption of a technique of secure identification in open cholecystectomy in which both cystic structures are putatively identified after which the gallbladder is taken off the cystic plate so that it is hanging free and just attached by the two cystic structures. In laparoscopic surgery complete separation of the body of the gallbladder from the cystic plate makes clipping of the cystic structures difficult so for laparoscopy the requirement was that only the lower part of the gallbladder (about one-third) had to be separated from the cystic plate. The other two requirements are that the hepatocystic triangle is cleared of fat and fibrous tissue and that there are two and only two structures attached to the gallbladder and the latter requirements were the same as in the open technique. Not until all three elements of CVS are attained may the cystic structures be clipped and divided. Intraoperatively CVS should be confirmed in a “time-out” in which the 3 elements of CVS are demonstrated. Note again that CVS is not a method of dissection but a method of target identification akin to concepts used in safe hunting procedures. Several years after the CVS was introduced there did not seem to be a lessening of biliary injuries.

Operative notes of biliary injuries were collected and studied in an attempt to determine if CVS was failing to prevent injury. We found that the method of target identification that was failing was not CVS but the infundibular technique in which the cystic duct is identified by exposing the funnel shape where the infundibulum of the gallbladder joins the cystic duct. This seemed to occur most frequently under conditions of severe acute or chronic inflammation. Inflammatory fusion and contraction may cause juxtaposition or adherence of the common hepatic duct to the side of the gallbladder. When the infundibular technique of identification is used under these conditions a compelling visual deception that the common bile duct is the cystic duct may occur. CVS is much less susceptible to this deception because more exposure is needed to achieve CVS, and either the CVS is attained, by which time the anatomic situation is clarified, or operative conditions prevent attainment of CVS and one of several important “bail-out” strategies is used thus avoiding bile duct injury.

CVS must be considered as part of an overall schema of a culture of safety in cholecystectomy. When CVS cannot be attained there are several bailout strategies such a cholecystostomy or in the case of very severe inflammation discontinuation of the procedure and referral to a tertiary center for care. The most satisfactory bailout procedure is subtotal cholecystectomy of which there are two kinds. Subtotal fenestrating cholecystectomy removes the free wall of the gallbladder and ablates the mucosa but does not close the gallbladder remnant. Subtotal reconstituting cholecystectomy closes the gallbladder making a new smaller gallbladder. Such a gallbladder remnant is undesirable since it may become the site of new gallstone formation and recurrent symptoms . Both types may be done laparoscopically.”

Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg 1995;180:101-25.

BASICS OF SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

This e-book was designed to assist in learning related to experimental surgical technique, during the training of health professionals. Concisely and objectively, it presents the basic principles for professional practice in surgery and in basic techniques of the most relevant surgical procedures. It is directed to the training of general practitioners, through the technical base, illustrated in procedures described step by step, with reference to the routines of the discipline of Surgical Technique, at the Federal University of Maranhão. It is not a work aimed at surgical clinic nor does it presuppose a descriptive detail that definitively supplies the necessary information for the execution of procedures in patients. This book is specially dedicated to undergraduate students, to serve as a guide during the Experimental Surgical Technique. It was designed and structured in order to facilitate theoretical study and encourage practical learning. Assisting your training, we seek professionals better prepared for health care.

Good Studies.

Covid-19 and Digestive Surgery

The current world Covid-19 pandemic has been the most discussed topic in the media and scientific journals. Fear, uncertainty, and lack of knowledge about the disease may be the significant factors that justify such reality. It has been known that the disease presents with a rapidly spreading, it is significantly more severe among the elderly, and it has a substantial global socioeconomic impact. Besides the challenges associated with the unknown, there are other factors, such as the deluge of information. In this regard, the high number of scientific publications, encompassing in vitro, case studies, observational and randomized clinical studies, and even systematic reviews add up to the uncertainty. Such a situation is even worse when considering that most healthcare professionals lack adequate knowledge to critically appraise the scientific method, something that has been previously addressed by some authors. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that expert societies supported by data provided by the World Health Organization and the National Health Department take the lead in spreading trustworthy and reliable information.

Discover our surgical video channel and lectures associated with the surgeon blog.

Share and Join: https://linktr.ee/TheSurgeon

#Medicine #Surgery #GeneralSurgery #DigestiveSurgery

#TheSurgeon #OzimoGama

Laparoscopic JEJUNOSTOMY

Many oncological patients with upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract tumours, apart from other symptoms, are malnourished or cachectic at the time of presentation. In these patients feeding plays a crucial role, including as part of palliative treatment. Many studies have proved the benefits of enteral feeding over parenteral if feasible. Depending on the tumour’s location and clinical stage there are several options of enteral feeding aids available. Since the introduction of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) and its relatively easy application in most patients, older techniques such as open gastrostomy or jejunostomy have rather few indications.

The majority of non-PEG techniques are used in patients with upper digestive tract, head and neck tumours or trauma that renders the PEG technique unfeasible or unsafe for the patient. In these patients, especially with advanced disease requiring neoadjuvant chemotherapy or palliative treatment, open gastrostomy and jejunostomy were the only options of enteral access. Since the first report of laparoscopic jejunostomy by O’Regan et al. in 1990 there have been several publications presenting techniques and outcomes of laparoscopic feeding jejunostomy. Laparoscopic jejunostomy can accompany staging or diagnostic laparoscopy for upper GI malignancy when the disease appears advanced, hence avoiding additional anaesthesia and an operation in the near future.

In this video the author describe the technique of laparoscopic feeding jejunostomy applied during the staging laparoscopy in patient with advanced upper gastrointestinal tract cancer with co-morbid cachexy, requiring enteral feeding and neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Welcome and get to know our Social Networks through the following link

Ozimo Gama’s Social Medias

#AnatomiaHumana #CirurgiaGeral #CirurgiaDigestiva #TheSurgeon

Traqueostomia

Basicamente, existem quatro situações que indicam a realização de traqueostomia: prevenção de lesões laringotraqueais pela intubação translaríngea prolongada; desobstrução da via aérea superior, em casos de tumores, corpo estranho ou infecção; acesso à via aérea inferior para aspiração e remoção de secreções; e aquisição de via aérea estável em paciente que necessita de suporte ventilatório prolongado.

A substituição do tubo endotraqueal pela cânula de traqueostomia ainda acrescenta benefícios, proporcionando conforto e segurança do paciente. Algumas sociedades americanas sugerem que a traqueostomia deva ser sempre considerada para pacientes que necessitarão de ventilação mecânica prolongada, ou seja, por mais de 14 dias.

Muitas vezes, a decisão de se realizar uma traqueostomia é tomada pelo julgamento clínico de médicos, principalmente aqueles que trabalham em unidades de terapia intensiva. Isso envolve a análise de múltiplos fatores, tais como as características de cada paciente, o motivo pelo qual ocorreu a intubação, doenças associadas, resposta ao trata-mento e prognóstico individualizado. Embora haja uma tendência de indicação de traqueostomia precoce em pacientes neurocríticos e com trauma grave.

Benefícios Clínicos:

- Diminuição do trabalho respiratório

- Melhora da aspiração das vias aéreas

- Permitir a fonação

- Permitir a alimentação por via oral

- Menor necessidade de sedação

- Redução do risco de pneumonia associada à ventilação

mecânica - Diminuição do tempo de ventilação mecânica

- Diminuição do tempo de internação em unidades de terapia

intensiva - Redução da mortalidade

Tratamento Cirúrgico do Abscesso Hepático Piogênico

Introdução

O abscesso hepático piogênico (AHP) é uma condição infecciosa grave caracterizada por uma coleção encapsulada de material purulento no fígado. Frequentemente, essa condição é resultante de infecções bacterianas, originárias do trato biliar ou de fontes intra-abdominais, como diverticulite. O manejo do AHP requer uma abordagem multidisciplinar, combinando diagnóstico rápido, antibioticoterapia e, em muitos casos, intervenção cirúrgica. No Brasil, a mortalidade associada a essa condição pode variar de 10% a 20%, sendo particularmente elevada em pacientes com comorbidades, como diabetes e cirrose. A presente revisão discute as abordagens cirúrgicas no tratamento do AHP, com ênfase nos critérios de intervenção, técnicas cirúrgicas e melhores práticas para o cirurgião do aparelho digestivo.

Diagnóstico e Classificação

O diagnóstico precoce do AHP é essencial para determinar a abordagem terapêutica mais adequada. Exames de imagem, como ultrassonografia (USG) e tomografia computadorizada (TC), são as ferramentas primárias para identificar a extensão da lesão e guiar a tomada de decisões. A classificação dos abscessos hepáticos baseia-se em seu tamanho e características morfológicas:

- Abscessos pequenos (menores que 3 cm) podem, muitas vezes, ser tratados com antibioticoterapia isolada.

- Abscessos maiores (geralmente >5 cm) e multiloculados exigem drenagem percutânea ou intervenção cirúrgica.

A etiologia do AHP no Brasil é predominantemente associada a bactérias como Escherichia coli e Klebsiella pneumoniae, e pacientes imunocomprometidos, como diabéticos, estão em maior risco de desenvolver complicações graves.

Abordagem Terapêutica

O tratamento do AHP é multimodal e deve ser adaptado à gravidade do caso, com o uso combinado de antibióticos, drenagem percutânea e intervenção cirúrgica, quando necessário. As diretrizes atuais propõem um algoritmo terapêutico baseado no tamanho e nas características dos abscessos.

1. Antibioticoterapia

A antibioticoterapia empírica deve ser iniciada imediatamente após o diagnóstico, visando cobertura para bactérias gram-negativas e anaeróbias. Ciprofloxacina ou cefixima combinadas com metronidazol são frequentemente utilizadas no manejo de abscessos hepáticos não complicados. A escolha do antibiótico deve ser ajustada conforme os resultados das culturas de sangue e de amostras do abscesso, garantindo uma abordagem personalizada.

2. Drenagem Percutânea

A drenagem percutânea, guiada por USG ou TC, é o tratamento de escolha para abscessos maiores que 3 cm e uniloculares (Tipo II). Esse método minimamente invasivo apresenta uma alta taxa de sucesso, próxima a 90%, sendo eficaz na maioria dos casos. No entanto, falhas podem ocorrer em abscessos multiloculados ou com conteúdo viscoso ou necrótico, situações em que a drenagem percutânea se torna inadequada, necessitando de intervenção cirúrgica.

3. Intervenção Cirúrgica

A cirurgia está indicada em abscessos multiloculados grandes (>3 cm, Tipo III), em abscessos que não respondem à drenagem percutânea ou na presença de complicações, como ruptura do abscesso. A cirurgia pode envolver drenagem minimamente invasiva ou ressecção hepática, dependendo da complexidade do abscesso e da experiência do cirurgião. Abscessos maiores que 10 cm apresentam maior risco de complicações, e nesses casos, a drenagem cirúrgica pode ser preferível. A laparotomia é recomendada em situações de peritonite ou quando o abscesso é de difícil acesso para drenagem percutânea.

4. Laparoscopia

A laparoscopia é uma alternativa minimamente invasiva à cirurgia aberta, indicada em abscessos uniloculares de tamanho moderado. Essa técnica oferece vantagens significativas, como menor tempo de internação e recuperação mais rápida, além de menor risco de complicações pós-operatórias.

Aplicação na Cirurgia Digestiva

O papel do cirurgião do aparelho digestivo é central no manejo dos abscessos hepáticos, especialmente em casos que requerem intervenção cirúrgica. A drenagem percutânea deve ser considerada a primeira linha de tratamento sempre que viável, mas o cirurgião deve estar preparado para realizar intervenções mais invasivas quando necessário. A laparoscopia tem demonstrado resultados promissores, reduzindo o tempo de internação e o risco de complicações. No Brasil, as infecções intra-abdominais complicadas são uma das principais causas de internação em emergências cirúrgicas, e o manejo adequado desses casos depende de uma sólida formação técnico-cirúrgica.

Algoritmo de Tratamento

Com base nas evidências disponíveis, um algoritmo de tratamento para o AHP pode ser delineado da seguinte forma:

- Abscessos pequenos (<3 cm, Tipo I): Tratamento com antibióticos isolados.

- Abscessos grandes uniloculares (>3 cm, Tipo II): Drenagem percutânea associada a antibioticoterapia.

- Abscessos grandes multiloculados (>3 cm, Tipo III): Intervenção cirúrgica.

Pontos-Chave

- Diagnóstico Precoce: O uso da TC com contraste é fundamental para o diagnóstico preciso do tamanho e da localização dos abscessos hepáticos, orientando a decisão terapêutica.

- Intervenção Cirúrgica: Abscessos multiloculados ou maiores que 5 cm frequentemente requerem intervenção cirúrgica, especialmente quando a drenagem percutânea falha.

- Abordagem Minimamente Invasiva: A laparoscopia oferece uma alternativa eficaz à cirurgia aberta, proporcionando uma recuperação mais rápida e com menor morbidade.

- Manejo Integral pelo Cirurgião Digestivo: O conhecimento técnico-cirúrgico é essencial para o manejo de abscessos hepáticos complexos, garantindo uma abordagem eficaz e personalizada.

Conclusão

O manejo do abscesso hepático piogênico exige uma abordagem multidisciplinar, sendo o cirurgião digestivo uma peça-chave no tratamento de casos complexos. A decisão entre drenagem percutânea e intervenção cirúrgica deve considerar múltiplos fatores, como o tamanho do abscesso, a resposta ao tratamento conservador e as condições clínicas do paciente. Como afirmou o Prof. Henri Bismuth: “Le traitement chirurgical n’est pas seulement une question de technique, mais de jugement. Le moment de l’intervention est aussi important que l’intervention elle-même.” Assim, o domínio técnico e a tomada de decisões precisas são fundamentais para o sucesso terapêutico no tratamento do AHP.

Gostou ❔Nos deixe um comentário ✍️, compartilhe em suas redes sociais e|ou mande sua dúvida pelo 💬 Chat On-line em nossa DM do Instagram.

#AbscessoHepatico #CirurgiaDigestiva #TratamentoAbscesso #DrenagemPercutanea #AparelhoDigestivo

Ebook: Princípios da Anatomia Topográfica

Os conceitos fundamentais da Anatomia Topográfica Humana através do estudo das regiões anatômicas com maior relevância Médico-Cirúrgica. Agora com amplo material multimídia disponibilizado através de acesso on-line dentro do livro e com isso creditamos que este trabalho será útil como mais uma ferramenta didática na preparação profissional dos estudantes de Medicina.

Link para Download

Fale Conosco

Ischaemic Preconditioning applied to LIVER SURGERY

- INTRODUCTION

The absence of oxygen and nutrients during ischaemia affects all tissues with aerobic metabolism. Ischaemia of these tissues creates a condition which upon the restoration of circulation results in further inflammation and oxidative damage (reperfusion injury). Restoration of blood flow to an ischaemic organ is essential to prevent irreversible tissue injury, however reperfusion of the organ or tissues may result in a local and systemic inflammatory response augmenting tissue injury in excess of that produced by ischaemia alone. This process of organ damage with ischaemia being exacerbated by reperfusion is called ischaemia-reperfusion (IR). Regardless of the disease process, severity of IR injury depends on the length of ischaemic time as well as size and pre-ischaemic condition of the affected tissue. The liver is the largest solid organ in the body, hence liver IR injury can have profound local and systemic consequences, particularly in those with pre-existing liver disease. Liver IR injury is common following liver surgery and transplantation and remains the main cause of morbidity and mortality.

2. AETIOLOGY

The liver has a dual blood supply from the hepatic artery (20%) and the portal vein (80%). A temporary reduction in blood supply to the liver causes IR injury. This can be due to a systemic reduction or local cessation and restoration of blood flow. Liver resections are performed for primary or secondary tumours of the liver and carry a substantial risk of bleeding especially in patients with chronic liver disease. Significant blood loss is associated with increased transfusion requirements, tumour recurrence, complications and increased morbidity and mortality. Several methods of hepatic vascular control have been described in order to minimise blood loss during elective liver resection. The simplest and most common method is inflow occlusion by applying a tape or vascular clamp across the hepatoduodenal ligament (Pringle Manoeuvre). This occludes both the arterial and portal vein inflow to the liver and leads to a period of warm ischaemia (37 °C) to the liver parenchyma resulting in ‘warm’ IR injury when the temporary inflow occlusion is relieved. In major liver surgery, extensive mobilisation of the liver itself without inflow occlusion results in a significant reduction in hepatic oxygenation.

3. PATOPHYSIOLOGY and RISK FACTORS

A complex cellular and molecular network of hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC), leukocytes and cytokines play a role in the pathogenesis of IR injury. In general, both warm and cold ischaemia share similar mechanisms of injury. Hepatocyte injury is a predominant feature of warm ischaemia, whilst endothelial cells are more susceptible to cold ischaemic injury. There are currently no proven treatments for liver IR injury. Understanding this complex network is essential in developing therapeutic strategies in prevention and treatment of IR injury. Identifying risk factors for IR injury are extremely important in patient selection for liver surgery and transplantation. The main factors are the donor or patient age, the duration of organ ischaemia, presence or absence of liver steatosis and in transplantation whether the donor organ has been retrieved from a brain dead or cardiac death donor.

4. PREVENTION and TREATMENT

There is currently no accepted treatment for liver IR injury. Several pharmacological agents and surgical techniques have been beneficial in reducing markers of hepatocyte injury in experimental liver IR, however, they are yet to show clinical benefit in human trials. The following is an outline of current and future strategies which may be effective in reducing the detrimental effects of liver IR injury in liver surgery and transplantation.

4.1 SURGICAL STRATEGIES

Inflow occlusion or portal triad clamping (PTC) can be continuous or intermittent; alternating between short periods of inflow occlusion and reperfusion. Intermittent clamping (IC) increases parenchymal tolerance to ischaemia. Hence, prolonged continuous inflow occlusion rather than short intermittent periods results in greater degree of post-operative liver dysfunction. IC permits longer total ischaemia times for more complex resections. Alternating between 15 min of inflow occlusion and 5 min reperfusion cycles can be performed safely for up to 120 min total ischaemia time. There is a potential risk of increased blood loss during the periods of no inflow occlusion. However, these intervals provide an opportunity for the surgeon to check for haemostasis and control small bleeding areas from the cut surface of the liver. The optimal IC cycle times are not clear, although intermittent cycles of up to 30 min inflow occlusion have also been reported with no increase in morbidity, blood loss or liver dysfunction compared to 15 min cycles. IC is particularly beneficial in reducing post-operative liver dysfunction in patients with liver cirrhosis or steatosis.

In liver surgery, IPC ( Ischaemic Preconditioning) involves a short period of ischaemia (10 min) and reperfusion (10 min) intraoperatively by portal triad clamping prior to parenchymal transection during which a longer continuous inflow occlusion is applied to minimise blood loss. It allows continuous ischaemia times of up to 40 min without significant liver dysfunction. However, the protective effect of IPC decreases with increasing age above 60 years old and compared to IC it is less effective in steatotic livers. Moreover, IPC may impair liver regeneration capacity and may not be tolerated by the small remnant liver in those with more complex and extensive liver resections increasing the risk of post-operative hepatic insufficiency.

In order to avoid direct ischaemic insult to the liver by inflow occlusion, remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) has been used. RIPC involves preconditioning a remote organ prior to ischaemia of the target organ. It has been shown to be reduce warm IR injury to the liver in experimental studies. A recent pilot randomised trial of RIPC in patients undergoing major liver resection for colorectal liver metastasis used a tourniquet applied to the right thigh with 10 min cycles of inflation-deflation to induce IR injury to the leg for 60 min. This was performed after general anaesthesia prior to skin incision. A reduction in post-operative transaminases and improved liver function was shown without the use of liver inflow occlusion. These results are promising but require validation in a larger trial addressing clinical outcomes.

5. FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Hepatic IR injury remains the main cause of morbidity and mortality in liver surgery and transplantation. Despite over two decades of research in this area, therapeutic options to treat or prevent liver IR are limited. This is primarily due to the difficulties in translation of promising agents into human clinical studies. Recent advances in our understanding of the immunological responses and endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of liver IR injury may pave the way for the development of new and more effective and targeted pharmacological agents.

Principles of Surgical Resection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

There has been significant improvement in the perioperative results following liver resection, mainly due to techniques that help reduce blood loss during the operation. Extent of liver resection required in HCC for optimal oncologic results is still controversial. On this basis, the rationale for anatomically removing the entire segment or lobe bearing the tumor, would be to remove undetectable tumor metastases along with the primary tumor.

SIZE OF TUMOR VERSUS TUMOR FREE-MARGIN

Several retrospective studies and meta-analyses have shown that anatomical resections are safe in patients with HCC and liver dysfunction, and may offer a survival benefit. It should be noted, that most studies are biased, as non-anatomical resections are more commonly performed in patients with more advanced liver disease, which affects both recurrence and survival. It therefore remains unclear whether anatomical resections have a true long-term survival benefit in patients with HCC. Some authors have suggested that anatomical resections may provide a survival benefit in tumors between 2 and 5 cm. The rational is that smaller tumors rarely involve portal structures, and in larger tumors presence of macrovascular invasion and satellite nodules would offset the effect of aggressive surgical approach. Another important predictor of local recurrence is margin status. Generally, a tumor-free margin of 1 cm is considered necessary for optimal oncologic results. A prospective randomized trial on 169 patients with solitary HCC demonstrated that a resection margin aiming at 2 cm, safely decreased recurrence rate and improved long-term survival, when compared to a resection margin aiming at 1 cm. Therefore, wide resection margins of 2 cm is recommended, provided patient safety is not compromised.

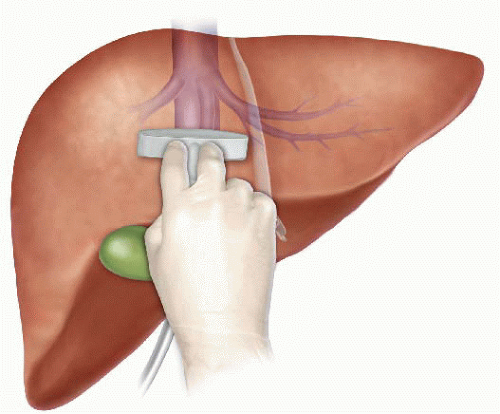

THECNICAL ASPECTS

Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) is an extremely important tool when performing liver resections, specifically for patients with HCC and compromised liver function. IOUS allows for localization of the primary tumor, detection of additional tumors, satellite nodules, tumor thrombus, and define relationship with bilio-vascular structures within the liver. Finally, intraoperative US-guided injection of dye, such as methylene-blue, to portal branches can clearly define the margins of the segment supplied by the portal branch and facilitate safe anatomical resection.

The anterior approach to liver resection is a technique aimed at limiting tumor manipulation to avoid tumoral dissemination, decrease potential for blood loss caused by avulsion of hepatic veins, and decrease ischemia of the remnant liver caused by rotation of the hepatoduodenal ligament. This technique is described for large HCCs located in the right lobe, and was shown in a prospective, randomized trial to reduce frequency of massive bleeding, number of patients requiring blood transfusions, and improve overall survival in this setting. This approach can be challenging, and can be facilitated by the use of the hanging maneuver.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that blood loss and blood transfusion administration are significantly associated with both short-term perioperative, and long-term oncological results in patients undergoing resection for HCC. This has led surgeons to focus on limiting operative blood loss as a major objective in liver resection. Transfusion rates of <20 % are expected in most experienced liver surgery centers. Inflow occlusion, by the use of the Pringle Maneuver represents the most commonly performed method to limit blood loss. Cirrhotic patients can tolerate total clamping time of up to 90 min, and the benefit of reduced blood loss outweighs the risks of inflow occlusion, as long as ischemia periods of 15 min are separated by at least 5 min of reperfusion. Total ischemia time of above 120 min may be associated with postoperative liver dysfunction. Additional techniques aimed at reducing blood loss include total vascular isolation, by occluding the inferior vena cava (IVC) above and below the liver, however, the hemodynamic results of IVC occlusion may be significant, and this technique has a role mainly in tumors that are adjacent to the IVC or hepatic veins.

Anesthesiologists need to assure central venous pressure is low (below 5 mmHg) by limiting fluid administration, and use of diuretics, even at the expense 470 N. Lubezky et al. of low systemic pressure and use of inotropes. After completion of the resection, large amount of crystalloids can be administered to replenish losses during parenchymal dissection.

LAPAROSCOPIC RESECTIONS

Laparoscopic liver resections were shown to provide benefits of reduced surgical trauma, including a reduction in postoperative pain, incision-related morbidity, and shorten hospital stay. Some studies have demonstrated reduced operative bleeding with laparoscopy, attributed to the increased intra-abdominal pressure which reduces bleeding from the low-pressured hepatic veins. Additional potential benefits include a decrease in postoperative ascites and ascites-related wound complications, and fewer postoperative adhesions, which may be important in patients undergoing salvage liver transplantation. There has been a delay with the use of laparoscopy in the setting of liver cirrhosis, due to difficulties with hemostasis in the resection planes, and concerns for possible reduction of portal flow secondary to increased intraabdominal pressure. However, several recent studies have suggested that laparoscopic resection of HCC in patients with cirrhosis is safe and provides improved outcomes when compared to open resections.

Resections of small HCCs in anterior or left lateral segments are most amenable for laparoscopic resections. Larger resections, and resection of posterior-sector tumors are more challenging and should only be performed by very experienced surgeons. Long-term oncological outcomes of laparoscopic resections was shown to be equivalent to open resections on retrospective studies , but prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings. In recent years, robotic-assisted liver resections are being explored. Feasibility and safety of robotic-assisted surgery for HCC has been demonstrated in small non-randomized studies, but more experience is needed, and long-term oncologic results need to be studied, before widespread use of this technique will be recommended.

ALPPS: Associating Liver Partition with Portal vein ligation for Staged hepatectomy

The pre-operative options for inducing atrophy of the resected part and hypertrophy of the FLR, mainly PVE, were described earlier. Associating Liver Partition with Portal vein ligation for Staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) is another surgical option aimed to induce rapid hypertrophy of the FLR in patients with HCC. This technique involves a 2-stage procedure. In the first stage splitting of the liver along the resection plane and ligation of the portal vein is performed, and in the second stage, performed at least 2 weeks following the first stage, completion of the resection is performed. Patient safety is a major concern, and some studies have reported increased morbidity and mortality with the procedure. Few reports exist of this procedure in the setting of liver cirrhosis. Currently, the role of ALPPS in the setting of HCC and liver dysfunction needs to be better delineated before more widespread use is recommended.

Pringle Maneuver

After the first major hepatic resection, a left hepatic resection, carried out in 1888 by Carl Langenbuch, it took another 20 years before the first right hepatectomy was described by Walter Wendel in 1911. Three years before, in 1908, Hogarth Pringle provided the first description of a technique of vascular control, the portal triad clamping, nowadays known as the Pringle maneuver. Liver surgery has progressed rapidly since then. Modern surgical concepts and techniques, together with advances in anesthesiological care, intensive care medicine, perioperative imaging, and interventional radiology, together with multimodal oncological concepts, have resulted in fundamental changes. Perioperative outcome has improved significantly, and even major hepatic resections can be performed with morbidity and mortality rates of less than 45% and 4% respectively in highvolume liver surgery centers. Many liver surgeries performed routinely in specialized centers today were considered to be high-risk or nonresectable by most surgeons less than 1–2 decades ago.Interestingly, operative blood loss remains the most important predictor of postoperative morbidity and mortality, and therefore vascular control remains one of the most important aspects in liver surgery.

“Bleeding control is achieved by vascular control and optimized and careful parenchymal transection during liver surgery, and these two concepts are cross-linked.”

First described by Pringle in 1908, it has proven effective in decreasing haemorrhage during the resection of the liver tissue. It is frequently used, and it consists in temporarily occluding the hepatic artery and the portal vein, thus limiting the flow of blood into the liver, although this also results in an increased venous pressure in the mesenteric territory. Hemodynamic repercussion during the PM is rare because it only diminishes the venous return in 15% of cases. The cardiovascular system slightly increases the systemic vascular resistance as a compensatory response, thereby limiting the drop in the arterial pressure. Through the administration of crystalloids, it is possible to maintain hemodynamic stability.

In the 1990s, the PM was used continuously for 45 min and even up to an hour because the depth of the potential damage that could occur due to hepatic ischemia was not yet known. During the PM, the lack of oxygen affects all liver cells, especially Kupffer cells which represent the largest fixed macrophage mass. When these cells are deprived of oxygen, they are an endless source of production of the tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukins 1, 6, 8 and 10. IL 6 has been described as the cytokine that best correlates to postoperative complications. In order to mitigate the effects of continuous PM, intermittent clamping of the portal pedicle has been developed. This consists of occluding the pedicle for 15 min, removing the clamps for 5 min, and then starting the manoeuvre again. This intermittent passage of the hepatic tissue through ischemia and reperfusion shows the development of hepatic tolerance to the lack of oxygen with decreased cell damage. Greater ischemic tolerance to this intermittent manoeuvre increases the total time it can be used.

Management of gallbladder cancer

Gallbladder cancer is uncommon disease, although it is not rare. Indeed, gallbladder cancer is the fifth most common gastrointestinal cancer and the most common biliary tract cancer in the United States. The incidence is 1.2 per 100,000 persons per year. It has historically been considered as an incu-rable malignancy with a dismal prognosis due to its propensity for early in-vasion to liver and dissemination to lymph nodes and peritoneal surfaces. Patients with gallbladder cancer usually present in one of three ways: (1) advanced unresectable cancer; (2) detection of suspicious lesion preoperatively and resectable after staging work-up; (3) incidental finding of cancer during or after cholecystectomy for benign disease.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Although, many studies have suggested improved survival in patients with early gallbladder cancer with radical surgery including en bloc resection of gallbladder fossa and regional lymphadenectomy, its role for those with advanced gallbladder cancer remains controversial. First, patients with more advanced disease often require more extensive resections than early stage tumors, and operative morbidity and mortality rates are higher. Second, the long-term outcomes after resection, in general, tend to be poorer; long-term survival after radical surgery has been reported only for patients with limited local and lymph node spread. Therefore, the indication of radical surgery should be limited to well-selected patients based on thorough preoperative and intra-operative staging and the extent of surgery should be determined based on the area of tumor involvement.

Surgical resection is warranted only for those who with locoregional disease without distant spread. Because of the limited sensitivity of current imaging modalities to detect metastatic lesions of gallbladder cancer, staging laparoscopy prior to proceeding to laparotomy is very useful to assess the

abdomen for evidence of discontinuous liver disease or peritoneal metastasis and to avoid unnecessary laparotomy. Weber et al. reported that 48% of patients with potentially resectable gallbladder cancer on preoperative imaging work-up were spared laparotomy by discovering unresectable disease by laparoscopy. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be avoided when a preoperative cancer is suspected because of the risk of violation of the plane between tumor and liver and the risk of port site seeding.

The goal of resection should always be complete extirpation with microscopic negative margins. Tumors beyond T2 are not cured by simple cholecystectomy and as with most of early gallbladder cancer, hepatic resection is always required. The extent of liver resection required depends upon whether involvement of major hepatic vessels, varies from segmental resection of segments IVb and V, at minimum to formal right hemihepatectomy or even right trisectionectomy. The right portal pedicle is at particular risk for advanced tumor located at the neck of gallbladder, and when such involvement is suspected, right hepatectomy is required. Bile duct resection and reconstruction is also required if tumor involved in bile duct. However, bile duct resection is associated with increased perioperative morbidity and it should be performed only if it is necessary to clear tumor; bile duct resection does not necessarily increase the lymph node yield.

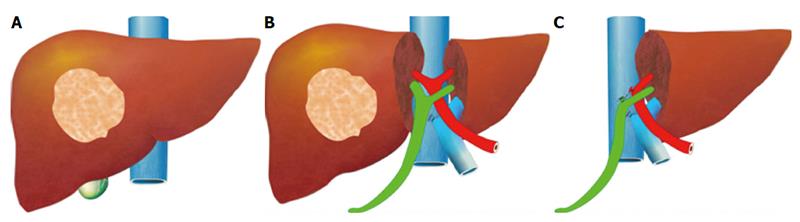

Hepatic Surgery: Portal Vein Embolization

INTRODUCTION

Portal vein Embolizations (PVE) is commonly used in the patients requiring extensive liver resection but have insufficient Future Liver Remanescent (FLR) volume on preoperative testing. The procedure involves occluding portal venous flow to the side of the liver with the lesion thereby redirecting portal flow to the contralateral side, in an attempt to cause hypertrophy and increase the volume of the FLR prior to hepatectomy.

PVE was first described by Kinoshita and later reported by Makuuchi as a technique to facilitate hepatic resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. The technique is now widely used by surgeons all over the world to optimize FLR volume before major liver resections.

PHYSIOPATHOLOGY

PVE works because the extrahepatic factors that induce liver hypertrophy are carried primarily by the portal vein and not the hepatic artery. The increase in FLR size seen after PVE is due to both clonal expansion and cellular hypertrophy, and the extent of post-embolization liver growth is generally proportional to the degree of portal flow diversion. The mechanism of liver regeneration after PVE is a complex phenomenon and is not fully understood. Although the exact trigger of liver regeneration remains unknown, several studies have identified periportal inflammation in the embolized liver as an important predictor of liver regeneration.

THECNICAL ASPECTS

PVE is technically feasible in 99% of the patients with low risk of complications. Studies have shown the FLR to increase by a median of 40–62% after a median of 34–37 days after PVE, and 72.2–80% of the patients are able to undergo resection as planned. It is generally indicated for patients being considered for right or extended right hepatectomy in the setting of a relatively small FLR. It is rarely required before extended left hepatectomy or left trisectionectomy, since the right posterior section (segments 6 and 7) comprises about 30% of total liver volume.

PVE is usually performed through percutaneous transhepatic access to the portal venous system, but there is considerable variability in technique between centers. The access route can be ipsilateral (portal access at the same side being resected) with retrograde embolization or contralateral (portal access through FLR) with antegrade embolization. The type of approach selected depends on a number of factors including operator preference, anatomic variability, type of resection planned, extent of embolization, and type of embolic agent used. Many authors prefer ipsilateral approach especially for right-sided tumors as this technique allows easy catheterization of segment 4 branches when they must be embolized and also minimizes the theoretic risk of injuring the FLR vasculature or bile ducts through a contralateral approach and potentially making a patient ineligible for surgery.

However, majority of the studies on contralateral PVE show it to be a safe technique with low complication rate. Di Stefano et al. reported a large series of contralateral PVE in 188 patients and described 12 complications (6.4%) only 6 of which could be related to access route and none precluded liver resection. Site of portal vein access can also change depending on the choice of embolic material selected which can include glue, Gelfoam, n-butyl-cyanoacrylate (NBC), different types and sizes of beads, alcohol, and nitinol plus. All agents have similar efficacy and there are no official recommendations for a particular type of agent.

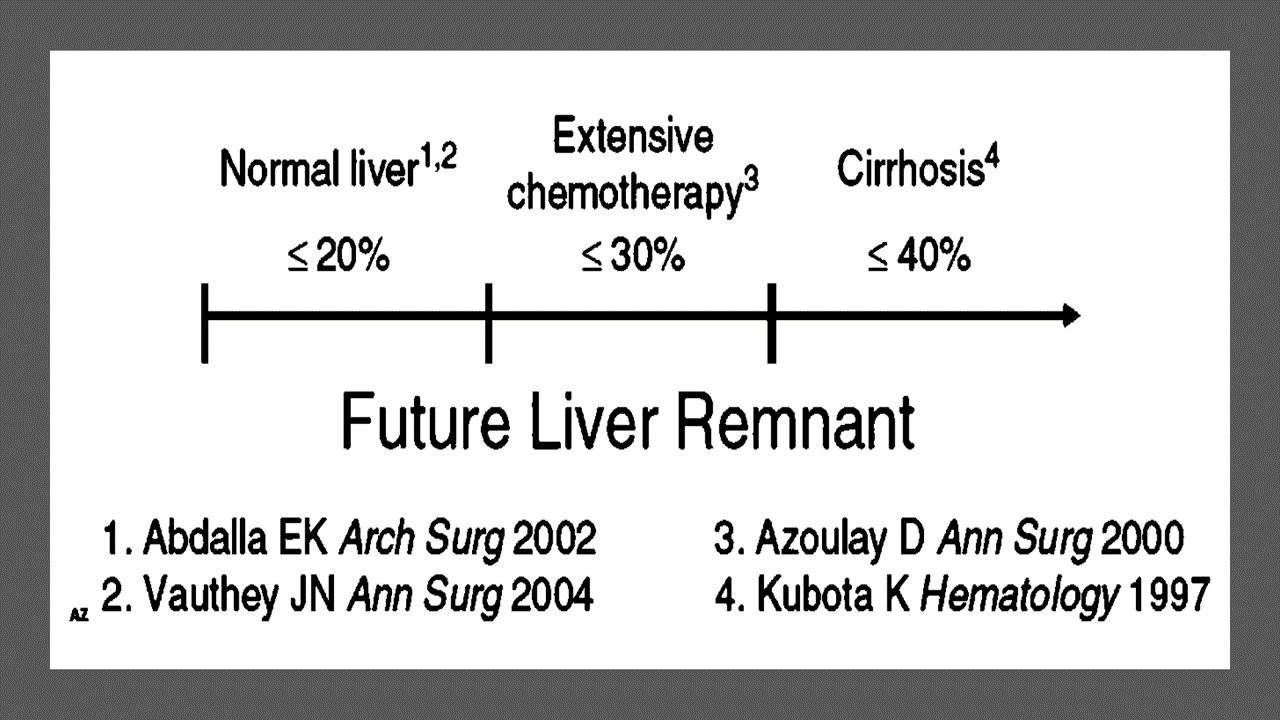

RESULTS