Prevention of Bile Duct Injury

Prevention of Bile Duct Injury During Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

Introduction

Bile duct injury (BDI) during laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a significant surgical complication with profound clinical and medico-legal implications. The incidence of BDI ranges from 0.3% to 0.6%, despite advances in surgical techniques and imaging modalities. The prevalence of BDI remains concerning due to its association with high morbidity and mortality rates. Patients who suffer from BDI often face prolonged hospital stays, multiple surgeries, and long-term complications such as bile leakage, strictures, and secondary biliary cirrhosis. Medico-legally, BDI is one of the most common reasons for litigation against surgeons, often resulting in significant financial settlements and professional repercussions.

Questions and Answers

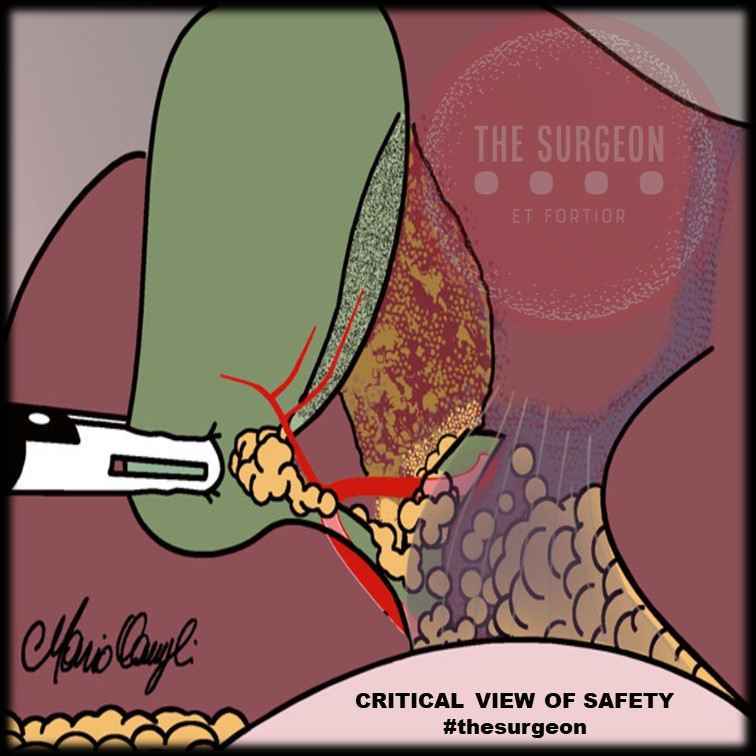

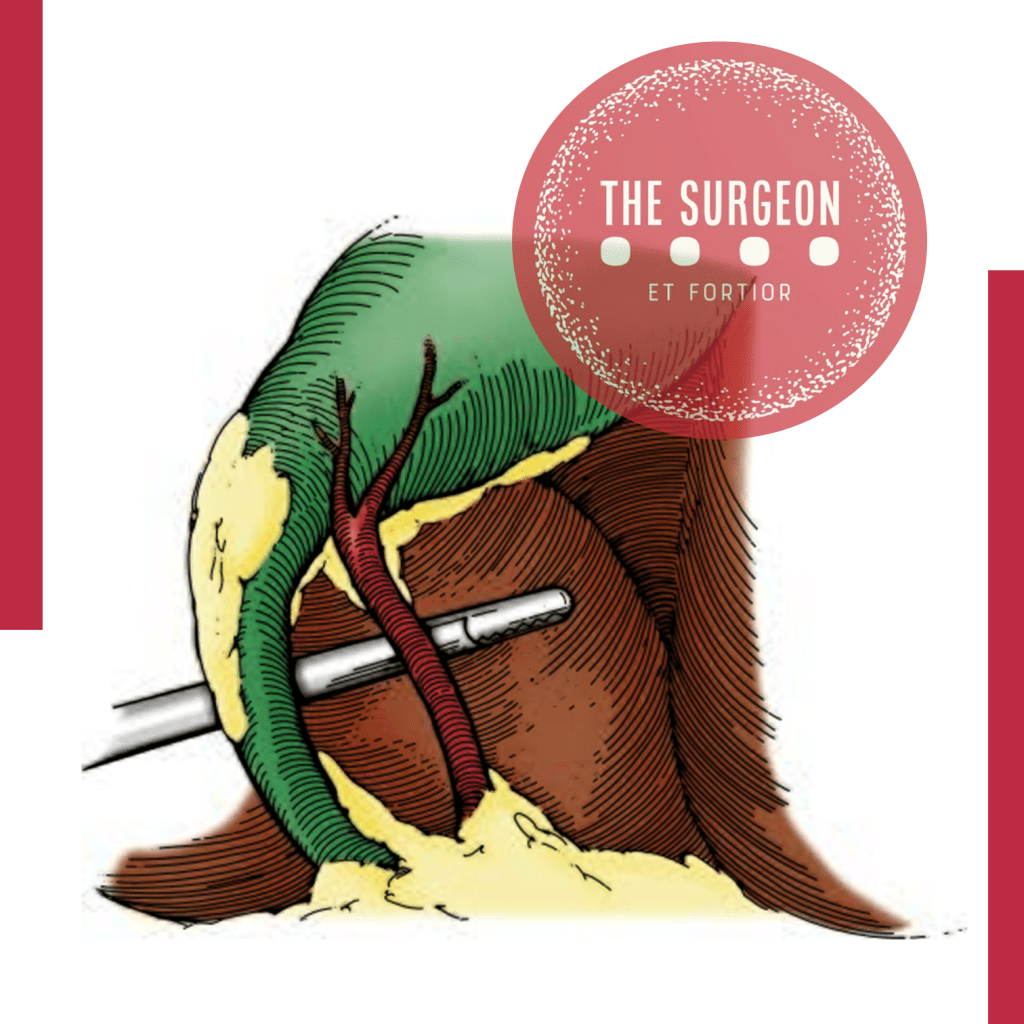

Question 1: What technique should be used to identify the anatomy during laparoscopic cholecystectomy?

Answer: The Critical View of Safety (CVS) is recommended for identifying the cystic duct and cystic artery.

Key Findings: The incidence of BDI was found to be 2 in one million cases using CVS, compared to 1.5 per 1000 cases with the infundibular technique.

Question 2: When should intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) be used?

Answer: IOC should be used in cases of anatomical uncertainty or suspicion of bile duct injury.

Key Findings: IOC aids in the prevention and immediate management of BDI by providing a precise assessment of biliary anatomy during surgery.

Question 3: What are the recommendations for managing patients with confirmed or suspected bile duct injury?

Answer: Patients with confirmed or suspected BDI should be referred to an experienced surgeon or a multidisciplinary hepatobiliary team.

Key Findings: Early referral to hepatobiliary specialists is associated with better long-term outcomes and lower complication rates.

Question 4: Should the “fundus-first” technique be used when CVS cannot be achieved?

Answer: Yes, the “fundus-first” technique is recommended when CVS cannot be achieved.

Key Findings: This technique is effective for safely dissecting the gallbladder in complex cases where anatomy is unclear.

Question 5: Should CVS be documented during laparoscopic cholecystectomy?

Answer: Yes, documenting CVS with double-static photographs is recommended.

Key Findings: Photographic documentation of CVS ensures correct anatomical identification and serves as a record for later review in case of complications.

Question 6: Should near-infrared biliary imaging be used intraoperatively?

Answer: The evidence for near-infrared biliary imaging is limited; thus, IOC is preferred.

Key Findings: IOC is more widely studied and proven effective in preventing BDI compared to near-infrared imaging.

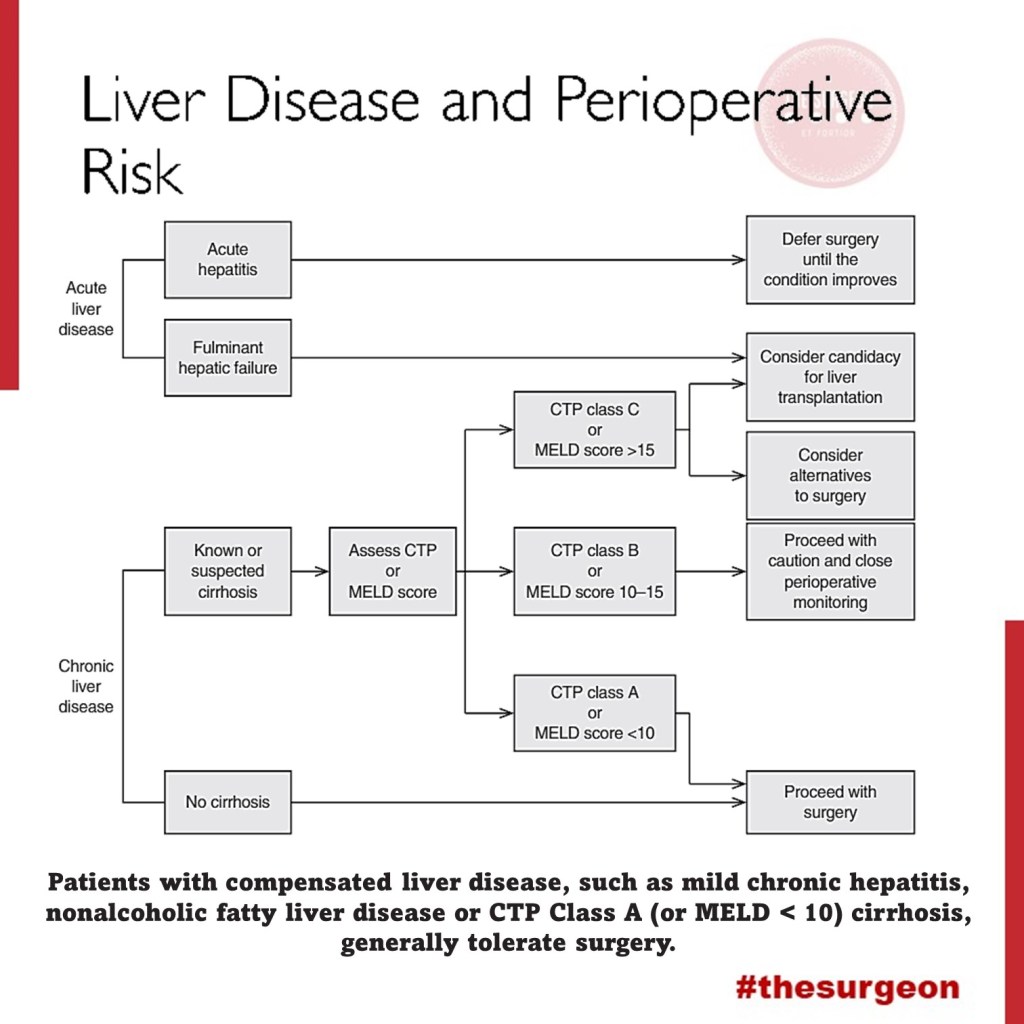

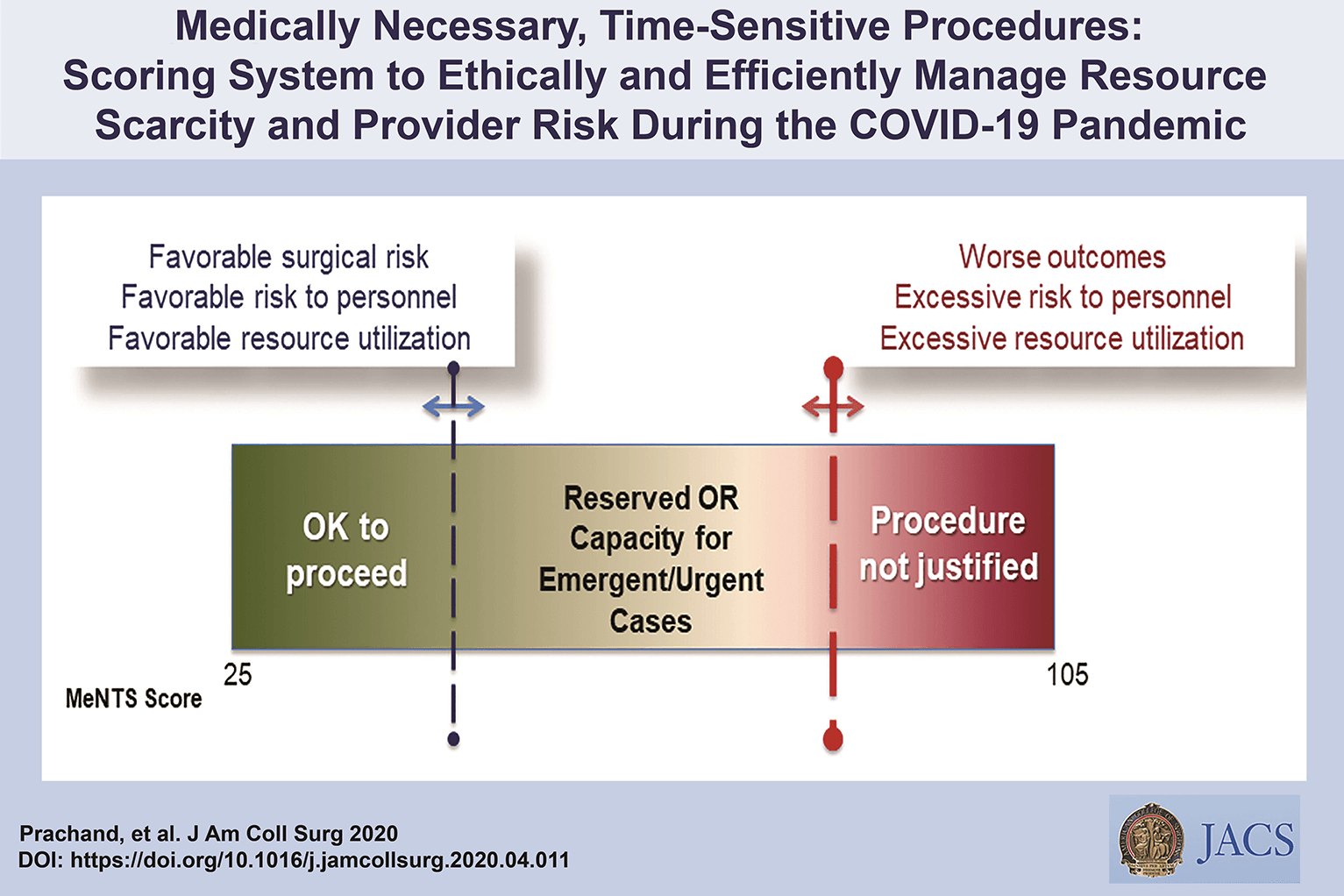

Question 7: Should surgical risk stratification be used to mitigate the risk of BDI?

Answer: Yes, surgical risk stratification is recommended.

Key Findings: Risk stratification helps identify patients at higher risk of complications, aiding in surgical planning and decision-making.

Question 8: Should the presence of cholecystolithiasis be considered in risk stratification?

Answer: Yes, the presence of cholecystolithiasis should be considered in risk stratification.

Key Findings: Patients with cholecystolithiasis have a higher risk of complications during cholecystectomy, making it important to include this condition in risk assessments.

Question 9: Should immediate cholecystectomy be performed in cases of acute cholecystitis?

Answer: Yes, immediate cholecystectomy within 72 hours is recommended.

Key Findings: Surgery within 72 hours of the onset of acute cholecystitis symptoms is associated with lower complication rates and better patient recovery.

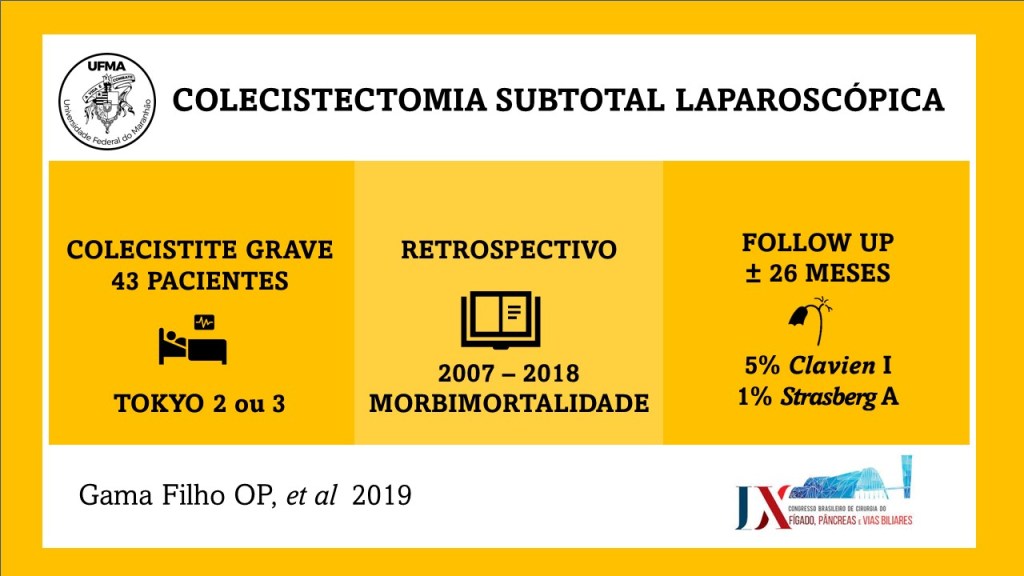

Question 10: Should subtotal cholecystectomy be performed in cases of severe inflammation?

Answer: Yes, subtotal cholecystectomy is recommended in cases of severe inflammation where CVS cannot be obtained.

Key Findings: In severe inflammation scenarios, subtotal cholecystectomy can facilitate the surgery and reduce the risk of BDI.

Question 11: Which approach is preferable, four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy or reduced-port/single-incision?

Answer: Four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy is recommended as the standard approach.

Key Findings: The four-port technique is the most studied, showing effectiveness and safety in performing cholecystectomies with lower complication risks.

Question 12: Should interval cholecystectomy be performed following percutaneous cholecystostomy?

Answer: Yes, interval cholecystectomy is recommended after initial stabilization with percutaneous cholecystostomy.

Key Findings: Interval cholecystectomy offers better long-term outcomes and lower risk of recurrent complications compared to no additional treatment.

Question 13: Should laparoscopic cholecystectomy be converted to open in difficult cases?

Answer: Yes, conversion to open surgery is recommended in cases of significant difficulty.

Key Findings: Conversion to open surgery can prevent BDI in situations where laparoscopic dissection is extremely difficult or risky.

Question 14: Should a waiting time be implemented to verify CVS?

Answer: Yes, a waiting time to verify CVS is recommended.

Key Findings: A waiting time allows better anatomical evaluation before proceeding with dissection, reducing the risk of BDI.

Question 15: Should two surgeons be used in complex cases?

Answer: The presence of two surgeons can be beneficial in complex cases, although strong recommendations are not made due to limited evidence.

Key Findings: Some studies suggest that collaboration between two surgeons can improve anatomical identification and reduce complications in difficult cases.

Question 16: Should surgeons receive coaching on CVS to limit the risk or severity of BDI?

Answer: Yes, surgeons should receive coaching on CVS.

Key Findings: Surgeons who receive targeted coaching on CVS show improved anatomical identification and reduced rates of BDI.

Question 17: Should simulation or video-based education be used to train surgeons?

Answer: Yes, simulation or video-based education should be used.

Key Findings: These training methods enhance technical skills, increase surgical precision, and reduce the incidence of BDI during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Conclusion

The consensus recommendations provide evidence-based approaches to minimize bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Practices such as the critical view of safety (CVS), intraoperative cholangiography (IOC), and early referral to specialists can significantly improve surgical outcomes and reduce complications. As famously stated, “The history of surgery is the history of the control of bleeding,” a phrase that underscores the importance of meticulous surgical technique and the prevention of complications like bile duct injuries.

Liderança no Campo da Cirurgia

O campo da cirurgia está em constante evolução, exigindo não apenas habilidades técnicas de alta qualidade, mas também capacidades de liderança excepcionais. No entanto, a formação tradicional dos cirurgiões raramente inclui treinamento formal em liderança, deixando muitos profissionais despreparados para assumir posições de liderança. Este artigo explora a importância da liderança na cirurgia, os diferentes tipos de liderança, suas características e oferece recomendações para o desenvolvimento de líderes cirúrgicos.

A Importância da Liderança na Cirurgia

Historicamente, os cirurgiões eram vistos como líderes incontestáveis dentro de um modelo de treinamento de aprendizado, onde a experiência pessoal e o julgamento clínico guiavam as práticas. No entanto, a modernização da medicina, impulsionada pela tecnologia e pela disponibilidade de dados, transformou o ambiente cirúrgico em um campo mais colaborativo e complexo. A liderança eficaz agora é crucial para navegar esse ambiente volátil, incerto, complexo e ambíguo. Como disse Napoleão Bonaparte, “Um líder é um negociador de esperanças.” Na cirurgia, liderar é guiar equipes em meio a incertezas, mantendo sempre a esperança e a confiança nos melhores resultados para os pacientes.

Desenvolvimento da Liderança Cirúrgica

Apesar da importância, muitos cirurgiões recém-formados não recebem treinamento formal em liderança durante a residência. Ao contrário de outras profissões, onde a liderança é um componente central da formação, os médicos devem aprender habilidades de liderança na prática ou através da observação de líderes bem-sucedidos. Programas de desenvolvimento de liderança, semelhantes aos oferecidos a oficiais militares e executivos de negócios, poderiam beneficiar grandemente os cirurgiões. George S. Patton afirmou: “Não diga às pessoas como fazer as coisas, diga-lhes o que fazer e deixe que elas surpreendam você com seus resultados.” Essa filosofia pode ser aplicada na cirurgia, incentivando a autonomia e a inovação dentro das equipes cirúrgicas.

Tipos de Liderança em Cirurgia

Diversos estilos de liderança podem ser aplicados no campo da cirurgia, cada um com suas características únicas:

- Liderança Autoritária:

- Caracterizada por decisões centralizadas e controle rígido.

- Pode ser eficaz em situações de emergência onde decisões rápidas são necessárias.

“O verdadeiro gênio reside na capacidade de avaliar informações incertas, conflitantes, e perigosas.” Winston Churchill

- Liderança Hierárquica:

- Baseada em uma estrutura de comando clara.

- Útil em ambientes estruturados com protocolos bem definidos.

Sun Tzu, em “A Arte da Guerra”, escreveu: “Aquele que é prudente e espera por um inimigo imprudente será vitorioso.”

2. Liderança Transacional:

- Focada em recompensas e punições para alcançar resultados.

- Pode ser útil para manter a eficiência e a produtividade.

Douglas MacArthur disse: “Os soldados devem ter ganho pessoal de suas ações; isso estimula o cumprimento do dever.”

3. Liderança Transformacional:

- Inspira e motiva a equipe a alcançar metas além das expectativas.

- Promove inovação e mudanças positivas na prática cirúrgica.

“O maior líder não é necessariamente aquele que faz as maiores coisas. Ele é aquele que faz as pessoas fazerem as maiores coisas.” – Ronald Reagan

4. Liderança Adaptativa:

- Envolve a capacidade de ajustar-se a novas situações e desafios.

- Crucial em ambientes cirúrgicos dinâmicos e em constante mudança.

Dwight D. Eisenhower afirmou: “Os planos são inúteis, mas o planejamento é tudo.”

5. Liderança Situacional:

- Adapta o estilo de liderança com base nas necessidades específicas da equipe e da situação.

- Proporciona flexibilidade e resposta eficaz a diferentes cenários clínicos.

Como observou Alexander, o Grande: “Não há nada impossível para aquele que tentará.”

6. Liderança Servidora:

- Foca no bem-estar e no desenvolvimento dos membros da equipe.

- Constrói uma cultura de apoio e colaboração.

“O melhor dos líderes é aquele cujo trabalho é feito, cujas pessoas dizem: ‘Nós fizemos isso sozinhos.'” – Lao-Tzu

Características de um Líder Cirúrgico Eficaz

Um líder cirúrgico eficaz deve possuir várias qualidades essenciais, incluindo visão, flexibilidade, motivação, inteligência emocional (EI), empatia, adaptabilidade, confiança, confiabilidade, responsabilidade e habilidades de gestão. A visão permite ao líder definir e perseguir objetivos claros, enquanto a flexibilidade e a adaptabilidade são necessárias para navegar em um ambiente em rápida mudança. Napoleão Bonaparte afirmou: “A liderança é uma combinação de estratégia e caráter. Se você precisar dispensar um, dispense a estratégia.” Essa citação reflete a importância do caráter e da integridade na liderança cirúrgica. A inteligência emocional e a empatia são fundamentais para a comunicação eficaz e para a construção de relacionamentos sólidos dentro da equipe. A confiabilidade e a responsabilidade asseguram que o líder seja um exemplo a ser seguido, promovendo uma cultura de confiança e responsabilidade mútua.

Recomendações para o Desenvolvimento de Líderes Cirúrgicos

Para desenvolver habilidades de liderança, os cirurgiões devem buscar oportunidades de treinamento formal em liderança, participar de workshops e seminários, e buscar orientação de mentores experientes. A autoavaliação honesta e o feedback contínuo são essenciais para o crescimento pessoal e profissional. Além disso, a incorporação de programas de liderança nos currículos de residência cirúrgica pode preparar melhor os futuros cirurgiões para os desafios do campo. Estabelecer um ambiente que encoraje a liderança colaborativa e o desenvolvimento contínuo também é crucial para a formação de líderes eficazes.

Conclusão

A liderança no campo da cirurgia é essencial para enfrentar os desafios de um ambiente médico moderno e complexo. Desenvolver habilidades de liderança em cirurgiões pode melhorar significativamente os resultados dos pacientes e promover uma prática cirúrgica mais eficiente e colaborativa. Ao reconhecer a importância da liderança e investir em seu desenvolvimento, a comunidade cirúrgica pode assegurar um futuro mais brilhante e inovador para a medicina.

Fricção Cirúrgica: Desafios e Realidades no Centro Cirúrgico

Fricção Cirúrgica: Desafios e Realidades no Centro Cirúrgico

No universo da teoria militar, Carl von Clausewitz introduziu o conceito de “fricção” para descrever as dificuldades e imprevistos que complicam a execução dos planos de guerra. Esse conceito, no entanto, transcende o campo de batalha e encontra paralelos surpreendentes em outros cenários complexos e de alta pressão, como o centro cirúrgico. A “fricção cirúrgica” refere-se às diversas dificuldades que cirurgiões e equipes médicas enfrentam durante procedimentos, afetando a eficiência e os resultados esperados.

Imprevisibilidade e Complexidade

Assim como na guerra, a cirurgia está repleta de elementos imprevisíveis. Mesmo com um planejamento meticuloso e uma equipe altamente treinada, fatores inesperados podem surgir. Complicações anatômicas, reações adversas a medicamentos e condições pré-existentes do paciente são apenas alguns exemplos de imprevistos que podem alterar drasticamente o curso de uma operação.

“Tudo na guerra é simples, mas a coisa mais simples é difícil.” – Carl von Clausewitz

Equipamentos e Tecnologia

Embora a tecnologia moderna tenha revolucionado a medicina, ela também introduz sua própria forma de fricção. Equipamentos sofisticados podem falhar ou não funcionar conforme esperado. A calibração inadequada de máquinas, falhas de software em dispositivos médicos e até problemas de energia podem criar obstáculos significativos durante uma cirurgia. Manter e operar esses equipamentos requer um nível elevado de expertise técnica e atenção constante.

“A fricção é o único conceito que distingue amplamente a guerra real da guerra no papel.” – Carl von Clausewitz

Comunicação e Coordenação

A comunicação é crucial em um centro cirúrgico, onde cada membro da equipe desempenha um papel vital. Qualquer falha na transmissão de informações pode ter consequências sérias. Mal-entendidos entre cirurgiões, anestesistas, enfermeiros e técnicos podem levar a erros críticos. A coordenação eficaz é essencial para garantir que todos os procedimentos sejam executados sem problemas, desde a preparação do paciente até a conclusão da cirurgia.

“A mais triviais coisas, vistas no contexto de uma operação militar, parecem ir contra você.” – Carl von Clausewitz

Fatores Humanos

A fricção também emerge das variáveis humanas. Fadiga, estresse e pressão emocional podem afetar o desempenho dos profissionais de saúde. Cirurgiões e enfermeiros frequentemente trabalham em turnos longos e intensos, o que pode levar a lapsos de concentração e julgamento. A capacidade de um profissional de saúde de manter a calma e tomar decisões rápidas e precisas é testada continuamente no ambiente cirúrgico.

“A guerra é o domínio da incerteza; três quartos dos fatores sobre os quais a ação é baseada estão enfiados na névoa de maior ou menor incerteza.” – Carl von Clausewitz

Logística e Suprimentos

A logística desempenha um papel crítico no funcionamento suave de um centro cirúrgico. A disponibilidade de instrumentos estéreis, medicamentos e outros suprimentos médicos é fundamental. Qualquer atraso na entrega de suprimentos ou problemas com a esterilização de instrumentos pode interromper um procedimento e aumentar os riscos para o paciente.

“A guerra é a área da atividade humana mais suscetível à fricção.” – Carl von Clausewitz

Mitigando a Fricção Cirúrgica

Assim como os comandantes militares desenvolvem estratégias para mitigar a fricção na guerra, as equipes cirúrgicas adotam várias práticas para reduzir as dificuldades inesperadas. Treinamento rigoroso e contínuo, simulações de procedimentos complexos e protocolos claros de comunicação são essenciais. Além disso, a manutenção regular de equipamentos e a implementação de sistemas de redundância podem ajudar a minimizar falhas técnicas.

“A habilidade de um líder militar reside na manutenção de uma visão clara e objetiva apesar da fricção.” – Carl von Clausewitz

A fricção cirúrgica, como descrita por Clausewitz em um contexto militar, reflete a realidade desafiadora do centro cirúrgico. Reconhecer e preparar-se para essas dificuldades é crucial para garantir a segurança do paciente e o sucesso das operações. Em última análise, a habilidade das equipes médicas em gerenciar a fricção cirúrgica determina a eficácia e a eficiência das intervenções cirúrgicas.

Charlie Munger’s 25 Cognitive Biases Applied to Digestive Surgery

In the demanding field of digestive surgery, excellence is not just a goal but a necessity. By integrating the profound insights of Charlie Munger on cognitive biases with the motivational principles of Zig Ziglar, surgeons can achieve superior performance and enhance patient care. This comprehensive guide offers actionable recommendations and illustrative examples tailored to the unique challenges of digestive surgery, ensuring that every decision is informed, balanced, and patient-centered. Charlie Munger is a renowned investor and philosopher known for his ability to identify and avoid judgment errors, often rooted in cognitive biases. For a digestive surgeon, understanding and mitigating these biases can significantly enhance clinical decision-making and performance. This summary outlines Munger’s 25 biases and provides specific examples and recommendations for surgical practice.

The 25 Cognitive Biases

- Reward and Punishment Super-Response Tendency

- Example: Opting for procedures with higher financial incentives despite less lucrative alternatives being more appropriate for the patient.

- Recommendation: Always evaluate the long-term benefits for the patient over immediate rewards.

- Liking/Loving Tendency

- Example: Ignoring a team member’s faults because you like them, compromising care quality.

- Recommendation: Maintain objective and impartial evaluations of all team members’ performance.

- Disliking/Hating Tendency

- Example: Dismissing valuable suggestions from colleagues due to personal dislike.

- Recommendation: Prioritize the efficacy of suggestions and patient safety, regardless of who proposes them.

- Doubt-Avoidance Tendency

- Example: Sticking to familiar procedures and avoiding new techniques with better outcomes due to fear of the unknown.

- Recommendation: Stay updated with best practices and be willing to explore new, evidence-based approaches.

- Inconsistency-Avoidance Tendency

- Example: Persisting with outdated surgical techniques to remain consistent with past practices.

- Recommendation: Regularly review clinical guidelines and adapt as necessary.

- Curiosity Tendency

- Example: Spending excessive time researching rare conditions not relevant to daily practice.

- Recommendation: Focus on continuous updates in areas directly related to daily clinical work.

- Kantian Fairness Tendency

- Example: Treating all cases identically without considering individual patient needs.

- Recommendation: Personalize care to meet the unique needs of each patient.

- Envy/Jealousy Tendency

- Example: Allowing jealousy of colleagues’ success to affect the work environment.

- Recommendation: Focus on personal and collaborative professional development, celebrating others’ successes.

- Reciprocity Tendency

- Example: Rewarding personal favors with clinical decisions, like preferences for shifts or cases.

- Recommendation: Maintain professionalism and base decisions on clinical and ethical criteria.

- Simple, Pain-Avoiding Psychological Denial

- Example: Avoiding discussions about poor prognoses to evade emotional discomfort.

- Recommendation: Address all clinical situations honestly and sensitively, providing appropriate support.

- Excessive Self-Regard Tendency

- Example: Overestimating personal skills and refusing assistance or second opinions.

- Recommendation: Recognize personal limitations and seek collaboration when necessary.

- Over-Optimism Tendency

- Example: Underestimating surgical risks and failing to prepare patients for potential complications.

- Recommendation: Conduct comprehensive risk assessments and communicate realistically with patients.

- Deprival-Superreaction Tendency

- Example: Overreacting to resource shortages impulsively.

- Recommendation: Plan ahead and stay calm to find effective solutions.

- Social-Proof Tendency

- Example: Adopting practices simply because they are popular among peers without assessing their efficacy.

- Recommendation: Base clinical decisions on robust evidence and recognized medical guidelines.

- Contrast-Misreaction Tendency

- Example: Underestimating a postoperative complication because it seems minor compared to a recent severe case.

- Recommendation: Evaluate each case individually and objectively, avoiding subjective comparisons.

- Stress-Influence Tendency

- Example: Making hasty decisions under high-pressure situations.

- Recommendation: Develop stress management techniques and make decisions calmly and deliberately.

- Availability-Misweighing Tendency

- Example: Making decisions based primarily on recent experiences instead of comprehensive historical data.

- Recommendation: Maintain detailed records and review long-term data to inform decisions.

- Use-It-or-Lose-It Tendency

- Example: Assuming surgical skills remain unchanged without regular practice.

- Recommendation: Regularly participate in training and simulations to keep skills up-to-date.

- Drug-Misinfluence Tendency

- Example: Underestimating the effects of postoperative analgesics.

- Recommendation: Carefully monitor medication use and adjust as needed.

- Senescence-Misinfluence Tendency

- Example: Resisting learning new surgical techniques due to age.

- Recommendation: Engage in continuous medical education and remain open to innovation.

- Authority-Misinfluence Tendency

- Example: Blindly following a senior colleague’s outdated practices.

- Recommendation: Question and validate all practices against current evidence and standards.

- Twaddle Tendency

- Example: Engaging in irrelevant discussions during surgical planning.

- Recommendation: Focus on relevant, evidence-based information.

- Reason-Respecting Tendency

- Example: Failing to explain the rationale behind surgical decisions to patients.

- Recommendation: Always provide clear, logical explanations to patients and their families.

- Lollapalooza Tendency

- Example: Multiple biases leading to a major error in patient care.

- Recommendation: Be vigilant about recognizing and mitigating multiple biases simultaneously.

- Tendency to Overweight Recent Information

- Example: Giving undue importance to the most recent piece of information received.

- Recommendation: Balance recent information with a thorough review of all relevant data.

Just as Charlie Munger highlights the importance of avoiding cognitive biases for effective decision-making, Zig Ziglar teaches us the significance of attitude and continuous improvement. For a digestive surgeon, applying these principles can transform clinical practice, leading to exceptional performance and superior patient care. Zig Ziglar said, “You don’t have to be great to start, but you have to start to be great.” Every step taken towards overcoming cognitive biases and adopting evidence-based practices is a step towards excellence. By recognizing and mitigating these 25 cognitive biases, you position yourself for an assistive performance that not only treats but truly cares for patients.

Recommendations from Zig Ziglar for Digestive Surgeons

- Believe in Yourself: “If you can dream it, you can achieve it.” Trust in your ability to learn and grow continually.

- Set Clear Goals: “A goal properly set is halfway reached.” Define clear objectives to enhance your skills and knowledge.

- Maintain a Positive Attitude: “Your attitude, not your aptitude, will determine your altitude.” Face challenges with a positive and resilient mindset.

- Learn from Every Experience: “Failure is an event, not a person.” Use every situation, good or bad, as a learning opportunity.

- Serve Others with Excellence: “You can have everything in life you want if you will just help enough other people get what they want.” Focus on patient well-being in all decisions.

By integrating Munger’s lessons and Ziglar’s motivational wisdom, you will not only become a better surgeon but also an inspiring leader and a true advocate for excellence in medicine. Remember always: “Success is doing the best we can with what we have.” Keep evolving, seeking knowledge, and above all, serving your patients with dedication and compassion. Together, let’s transform the practice of digestive surgery, one step at a time, towards the excellence our patients deserve.

Mondino de Luzzi (1270-1326) e o surgimento do MONITOR DE ANATOMIA

Mondino, oriundo de Bolonha, nasceu e concluiu seus estudos em sua cidade natal, obtendo sua graduação por volta do ano de 1290. A partir de 1306, tornou-se membro do corpo docente da universidade local. Ele recebeu instrução de Tadeu, compartilhando a mesma época de estudo com Mondeville, e dedicou-se de maneira sistemática à Anatomia, realizando dissecações públicas do corpo humano. Mondino é reconhecido como o pioneiro na “restauração” da Anatomia. Em 1316, publicou o tratado intitulado “Anothomia”, considerado o primeiro trabalho “moderno” na área, distinguindo-se por sua abordagem prática e original, diferenciando-se de simples traduções de textos clássicos.

A obra de Mondino apresenta desafios, conforme apontado por Singer (1996), destacando-se a nomenclatura confusa e as condições peculiares da dissecação naquela época. A ausência de conservantes apropriados, apesar do conhecimento acumulado pelos egípcios em técnicas de embalsamamento, tornava a dissecação um processo extenuante, preferencialmente realizado no inverno e em até quatro dias específicos para cada região do corpo.

Apesar de imprecisões anatômicas, como apontado por Friedman e Friedman (2001), Mondino desempenhou um papel crucial na instituição da dissecação como componente essencial do estudo anatômico. Essa prática foi posteriormente integrada ao currículo médico da Universidade de Bolonha, permitindo, até o final do século XVI, que as execuções de criminosos fossem realizadas de maneira que não comprometesse o trabalho anatômico, representando um avanço no uso do corpo humano na construção do conhecimento.

A contribuição de Mondino foi duradoura, pois sua obra foi uma das principais fontes de conhecimento em Anatomia humana por mais de duzentos anos, até o advento da obra de Vesalius no século XVI. Ao assumir a cátedra da disciplina, Mondino introduziu uma nova dinâmica nas aulas de Anatomia, afastando-se da dissecação e inserindo o ostensor (aluno) e o demonstrator ou incisore (técnico) para conduzirem os procedimentos, enquanto os alunos observavam.

As técnicas predominantes, como dissecação a fresco, maceração e preparações secas ao sol, eram utilizadas por Mondino e seus contemporâneos. Apesar de suas reservas quanto à maceração, essa técnica continuou a ser praticada, como confirmado pelos textos de Guido de Vigevano em 1345, representando a persistência do uso da dissecação para fins educacionais em Bolonha.

Mondino não expandiu significativamente o conhecimento anatômico existente, mas contribuiu para a formação de anatomistas que perpetuaram a tradição da disciplina em Bolonha, Pádua e em outros países. Notáveis estudiosos, como Gabrielle de Gerbi e Alessandro Achillini, aprimoraram e ampliaram as descrições anatômicas de Mondino em suas próprias contribuições.

A anatomia permanece como alicerce fundamental para o desenvolvimento da medicina ao oferecer conhecimentos cruciais para o adequada exercício profissional. O legado de anatomistas como Mondino, que enfrentaram desafios significativos em suas dissecações pioneiras, ecoa nas salas de aula modernas. A persistência do estudo anatômico é essencial para a formação médica, e os monitores de anatomia desempenham um papel vital nesse processo educativo. Atuando como elo entre a teoria e a prática, esses monitores, herdeiros contemporâneos do ostensor de Mondino, desempenham um papel crucial ao auxiliar na orientação dos alunos nas complexidades da dissecação e na compreensão da anatomia humana. Sua contribuição atual é inseparável do legado histórico, garantindo que o conhecimento anatômico continue a florescer, moldando as futuras gerações de profissionais de saúde e consolidando a anatomia como um pilar indispensável no edifício da medicina.

ODE AOS MESTRES ANATÔMICOS

Ser mestre é perpetuar juventude, Afrontando o inexorável fio do tempo, Desdobrando-se, multiplicando-se, Nas almas dos discípulos, criando ensejo.

Escolas germinam quando a maturidade, Se entrelaça à força do nobre sentimento, O mestre, sábio, fala à mente e coração, Exemplo luminoso, toque profundo, alento.

Na odisseia do saber, mestre é guia, Navegando oceanos de experiência viva, Com luz, desbrava trilhas no pensamento.

O mestre, como sol em seu zênite, Aquece a jornada do aprendizado, Conservando-se jovem, eternamente, erudito.

Assim, na sala de aula, é o comandante, Que com alma e sabedoria encanta, O mestre, semeando luz e meta.

Small desires have a life as short as the journey of those who pursue them.

The will is the road: those who want, move forward; those who don’t, justify.

Those who want find the way; those who don’t, know the reasons.

Those who want make sacrifice meaningful.

Those who don’t want declare the barriers that ease guilt.

Those who don’t want turn restriction into prohibition, limit into decision.

Those who want decide for the outcome to be achieved.

Those who don’t want decide based on the difficulty encountered.

What is challenging for one is motivating for another.

What is sacrifice for one is commitment for the other.

The challenge, for both, changes – irritating or exciting, obstacle or opportunity. Those who want accept and persist.

Those who don’t want retreat and give up.

The drive of man is his GREAT desire.

Small desires have a life as short as the journey of those who pursue them.

O Estoicismo Cirúrgico

Aplicando Princípios Filosóficos na Prática Cirúrgica

O campo da cirurgia, especialmente no tratamento das doenças do aparelho digestivo, exige não apenas habilidades técnicas refinadas, mas também resiliência emocional e ética sólida. A prática cirúrgica, por sua natureza, envolve decisões difíceis, momentos de pressão extrema e desafios inesperados. Nesse contexto, os princípios do estoicismo, filosofia praticada por pensadores como Sêneca, Epicteto e o imperador Marco Aurélio, oferecem ferramentas valiosas para que o cirurgião enfrente a complexidade emocional e ética de sua profissão.

Neste artigo, direcionado a estudantes de medicina, residentes de cirurgia geral e pós-graduandos em cirurgia do aparelho digestivo, vamos explorar como os princípios estoicos podem ser aplicados à prática cirúrgica, promovendo não apenas a eficiência técnica, mas também a excelência ética. Abordaremos as virtudes estoicas que podem moldar o comportamento de um cirurgião, aprimorando sua capacidade de lidar com adversidades e tomar decisões sábias no centro cirúrgico.

1. Aceitação das Limitações: “Primum non nocere” em Ação

O princípio estoico de aceitar o que não pode ser mudado é fundamental para o cirurgião. Em um procedimento cirúrgico, o inesperado pode surgir a qualquer momento. O estoicismo ensina que devemos focar no que está sob nosso controle – nossas ações e reações – e aceitar com serenidade aquilo que foge ao nosso alcance, como complicações imprevistas ou resultados adversos. Essa atitude fortalece o cirurgião, permitindo-lhe manter a calma e a clareza mental em situações críticas.

“O que está no meu poder é como reajo ao que acontece. O resto está fora do meu controle.” – Marco Aurélio

2. A Virtude da Perseverança em Meio às Adversidades

A cirurgia, especialmente nas doenças do aparelho digestivo, frequentemente envolve longos procedimentos, altos níveis de complexidade e a necessidade de ajustes rápidos. O estoicismo valoriza a perseverança diante de dificuldades, uma virtude essencial para o cirurgião que deve persistir no cuidado dos pacientes, mesmo em cenários complicados. A capacidade de continuar com foco e determinação, mesmo em circunstâncias adversas, é o que distingue o cirurgião estoico.

“A adversidade é uma oportunidade para a virtude.” – Marco Aurélio

3. Disciplina e Autocontrole no Centro Cirúrgico

O autocontrole é uma das virtudes centrais do estoicismo, e no campo cirúrgico, é vital que o cirurgião mantenha o controle emocional durante procedimentos complexos. O estoicismo nos ensina a não sermos controlados por emoções passageiras, como medo ou frustração, mas sim a agir com racionalidade. No centro cirúrgico, isso se traduz em decisões conscientes e calculadas, que priorizam o bem-estar do paciente, mantendo a objetividade diante de situações estressantes.

“Não é o que acontece, mas como você reage que importa.” – Marco Aurélio

4. Justiça e a Importância de Tratar Todos os Pacientes com Equidade

Para o cirurgião, a justiça, outro pilar estoico, é essencial. Todo paciente, independentemente de sua condição socioeconômica, deve receber o mesmo nível de cuidado e atenção. A prática cirúrgica ética requer que o cirurgião trate cada paciente com equidade, aplicando os princípios da medicina de maneira justa, sem preconceitos ou favoritismos. O cirurgião estoico vê em cada paciente uma oportunidade de exercer a sua profissão com justiça e integridade.

“A justiça consiste em fazer o que é correto, não o que é popular.” – Marco Aurélio

5. Coragem e Resiliência na Tomada de Decisões Difíceis

A cirurgia muitas vezes exige coragem para tomar decisões difíceis, especialmente em situações de risco à vida do paciente. A filosofia estoica valoriza a coragem como uma virtude indispensável. Para o cirurgião, isso significa enfrentar com firmeza e clareza os dilemas éticos e clínicos, mesmo quando há incertezas. A coragem estoica permite que o cirurgião aja com confiança e serenidade, tomando decisões informadas e moralmente corretas, mesmo em momentos críticos.

“A coragem é a dignidade sob pressão.” – Marco Aurélio

Conclusão

A prática cirúrgica é muito mais do que um conjunto de habilidades técnicas; é uma arte que exige um equilíbrio entre conhecimento, ética e resiliência emocional. Ao adotar os princípios estoicos, o cirurgião pode enfrentar os desafios diários com serenidade, perseverança e justiça, sempre em busca do bem maior para seus pacientes. O estoicismo oferece uma base filosófica robusta para lidar com as pressões da vida cirúrgica, fortalecendo o profissional em sua jornada por excelência técnica e moral.

“A felicidade de sua vida depende da qualidade de seus pensamentos.” – Marco Aurélio

Gostou ❔ Nos deixe um comentário ✍️, compartilhe em suas redes sociais e|ou mande sua dúvida pelo 💬 Chat On-line em nossa DM do Instagram.

#cirurgiageral #filosofiaestoica #éticaemcirurgia #estoicismonaetica #resiliencia

The Surgical Coach (P7)

Importance of OR Etiquette and Professionalism

The NOTTS emphasizes the significance of operating room (OR) etiquette and the evolution of surgical culture towards a more respectful and collaborative environment. Key points include:

- Changing Dynamics in the OR: The historical reputation of surgeons as being arrogant or demeaning, engaging in hazing practices, or displaying disruptive behavior is no longer acceptable. Modern surgeons are expected to create an atmosphere of mutual respect, trust, and communication.

- Cultural Shift towards Respect and Safety: A culture of safety and respect in the OR correlates with improved patient outcomes. It also enhances team communication, fosters professionalism, and contributes to a positive educational experience for all involved.

- Introduction to OR Etiquette: The concept of “OR etiquette” is introduced as a code of conduct among professionals that governs how they act and work together. This is distinct from manners, which are specific behaviors reflecting attitudes toward others.

- Components of OR Etiquette: The chapter covers various aspects of OR etiquette, including communication skills, leadership and followership, giving and receiving feedback, and available programs for improving team communication and culture.

- Team Members in the OR:

- Private Practice Setting: An attending surgeon, possibly with one or more assistants, which may include a second attending surgeon, certified surgical assistant (CSA), or physician assistant (PA).

- Academic Setting: Assistants may include medical students, residents, or fellows. Fellows are fully trained surgeons undergoing additional subspecialty training.

- Learning Environment: Progressive autonomy is a crucial concept, allowing learners to take on more responsibilities based on their competency level.

- Preoperative Discussion: Clear communication between the surgeon and the team members before the operation is essential. This includes discussing roles, responsibilities, and educational goals for the case.

- Patient-Centered Approach: Team members are responsible for reviewing the patient’s case in detail, understanding medical history, current disease status, medications, and diagnostic studies. A shared mental model of the operative and postoperative plan is crucial.

- Intraoperative Focus: During the operation, the patient becomes the central focus. Each team member is expected to contribute to the progress of the operation and assist others in doing the same.

- Postoperative Care Discussion: After the operation, discussions should cover postoperative care aspects, such as pain management, dietary restrictions, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, and prescription medications.

The series posts (The Surgical Coach) aims to guide professionals in developing a positive OR culture through adherence to etiquette, emphasizing teamwork, respect, and effective communication for improved patient outcomes and a better working environment.

The Surgical Coach (P6)

Promoting a Positive OR Environment: Manners and Etiquette

Maintaining a respectful and collaborative atmosphere in the operating room (OR) is crucial for effective teamwork and patient safety. The author outlines key manners and etiquette that contribute to a positive OR environment:

- Politeness: Being courteous and considerate in interactions with colleagues fosters a harmonious atmosphere.

- Respect: Treating everyone in the OR with respect, regardless of their role or position, is essential for teamwork.

- Humility: Remaining humble helps create a collaborative environment where everyone’s input is valued.

- Learning Names: Taking the time to learn and use the names of all team members enhances personal connections.

- Offering Help: Anticipating needs and offering assistance without being asked demonstrates a proactive and cooperative attitude.

- Asking for Help: Being willing to seek assistance when needed promotes a culture of mutual support.

- Expressing Gratitude: Thanking colleagues for their contributions acknowledges their efforts and encourages teamwork.

- Patient-Centered Focus: Keeping the patient at the center of all actions emphasizes the ultimate goal of providing quality care.

Avoiding Disruptive Behavior:

- Rude, disruptive, or disrespectful behavior is not tolerated.

- Avoid yelling, making sarcastic comments, or engaging in inappropriate jokes.

- Refrain from gossiping or denigrating others.

- When playing music, be considerate of others’ preferences, and turn it off during critical times like the initial time-out.

Social Media Etiquette in the OR:

- Stay professional when using social media in the OR.

- Avoid checking Facebook or Instagram during surgery.

- Exercise caution when posting online, as anything posted can be captured and spread.

- Refrain from posting identifiable patient information.

Effective Communication and Surgical Pause:

- Ongoing effective communication among the surgical team is crucial.

- Emphasizes the importance of the surgical pause or “time-out” to establish a shared mental model.

- Recommends using a structured checklist, such as the World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist, during the surgical pause.

- Highlights the checklist’s positive impact on reducing mortality, complications, and hospital length of stay.

- Encourages active engagement of all team members during the checklist process.

Customizing the Checklist:

- The surgical safety checklist can be modified by hospitals or services to include relevant items specific to their patient population.

- Designated leaders should review and discuss each item, ensuring that all team members are introduced and empowered to speak up if they identify potential safety concerns.

- Customization may include a debriefing section at the end of the case to address additional items relevant to the team’s specific practices.

In summary, promoting positive manners and etiquette, avoiding disruptive behavior, and utilizing effective communication tools contribute to a culture of safety and collaboration in the OR. The surgical safety checklist serves as a valuable tool when implemented with commitment and engagement from all team members.

The Surgical Coach (P5)

The Surgery Success Pyramid: Insights from Coach Wooden

Drawing inspiration from the legendary basketball coach John Wooden and his “pyramid of success,” the author has adapted the concept to create the “surgery success pyramid.” This modified pyramid is tailored to the field of surgery, emphasizing key elements for professional and personal success.

Foundational (1st Tier) Elements:

- Industriousness: Hard work and diligence remain foundational to success in surgery.

- Friendship: Emphasizes the importance of teamwork, collaboration, and camaraderie within the surgical profession.

- Loyalty: Stresses the significance of loyalty to colleagues, patients, and the profession.

- Cooperation: Highlights the need for effective collaboration and cooperation among members of the surgical team.

- Enthusiasm: Encourages a positive and passionate approach to the practice of surgery.

2nd Tier Elements:

- Self-Control: The ability to maintain composure and discipline in challenging situations.

- Alertness: Staying vigilant and aware of the evolving surgical environment.

- Initiative: Taking proactive steps to address challenges and improve surgical practices.

- Intentness: Maintaining a focused and determined mindset toward achieving surgical goals.

While the foundational and second-tier elements retain Wooden’s original principles, modifications have been made to better reflect the nuances of the surgical profession.

Take-Home Points for Success in Surgery:

The author concludes with practical advice for success at different stages of a surgical career:

- Medical Student Success:

- Study or practice for an average of 4 hours per day.

- Write at least one paper for the literature per year.

- Engage in lab work and aim for a minimum of three papers per year.

- Read medical journals regularly.

- Strive for academic excellence, including achieving membership in one surgical association.

- Keep a journal or log of patient encounters and lessons learned.

- Prioritize physical fitness.

- Resident Success:

- Dedicate at least 2 hours a day to deliberate practice and study.

- Write one paper per clinical year and a minimum of three papers per year during lab experience.

- Be a positive deviant by identifying and improving inefficient processes.

- Keep a journal or log of valuable clinical insights.

- Maintain physical fitness and well-being.

- Fulfill all residency requirements promptly.

- Junior Faculty Success :

- Focus on mastering surgical practice.

- Seek mentorship and engage in a mentor-mentee relationship.

- Embrace new challenges in education, research, and administration.

- Plan for a full career by considering long-term well-being and financial planning.

- Prioritize life outside the hospital, spending time with family and friends.

- Contribute to the literature and engage in teaching.

- Value colleagues and foster a sense of community within the surgical field.

The author underscores the fulfillment derived from a life dedicated to surgery, emphasizing the value of hard work, continuous learning, and contributions to the field.

The Surgical Coach (P4)

Atul Gawande’s Insights: Navigating Medicine’s Core Requirements

Atul Gawande, a celebrated author known for his insightful perspectives on healthcare, especially in the surgical realm, has provided valuable insights that resonate with medical professionals. In his book “Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance,” Gawande articulates three fundamental requirements for success in medicine:

- Diligence:

- Emphasizes the importance of meticulous attention to detail to prevent errors and overcome challenges.

- Do Right:

- Acknowledges that medicine is inherently a human profession, highlighting the ethical imperative to prioritize patient well-being.

- Ingenuity:

- Encourages a mindset of innovation, urging practitioners to think differently, embrace change, and learn from failures.

Gawande goes beyond defining these core requirements and offers five compelling suggestions on how individuals can make a positive impact within their professional culture:

- Ask an Unscripted Question:

- Advocates for spontaneous inquiries that can lead to unexpected discoveries and foster a culture of open communication.

- Don’t Complain:

- Advises against unproductive complaining, emphasizing that it neither solves problems nor contributes constructively to discussions. Encourages individuals to be prepared with alternative topics for discussion.

- Count Something:

- Promotes the practice of quantifying aspects of one’s work. Gawande suggests that counting something of personal interest leads to valuable insights and continuous learning.

- Write Something:

- Recognizes the transformative power of writing or typing. Encourages professionals to document experiences, insights, and reflections, enhancing both personal and collective learning.

- Change—Be an Early Adopter:

- Acknowledges the necessity of embracing change, especially in the rapidly advancing landscape of surgical technology. Urges individuals to be early adopters, staying abreast of innovations to enhance patient care.

Gawande’s guidance extends beyond the technical aspects of medicine, delving into the realms of communication, mindset, and professional development. These principles provide a roadmap for medical professionals to not only excel in their individual capacities but also positively influence the broader culture within which they operate.

The Surgical Coach (P3)

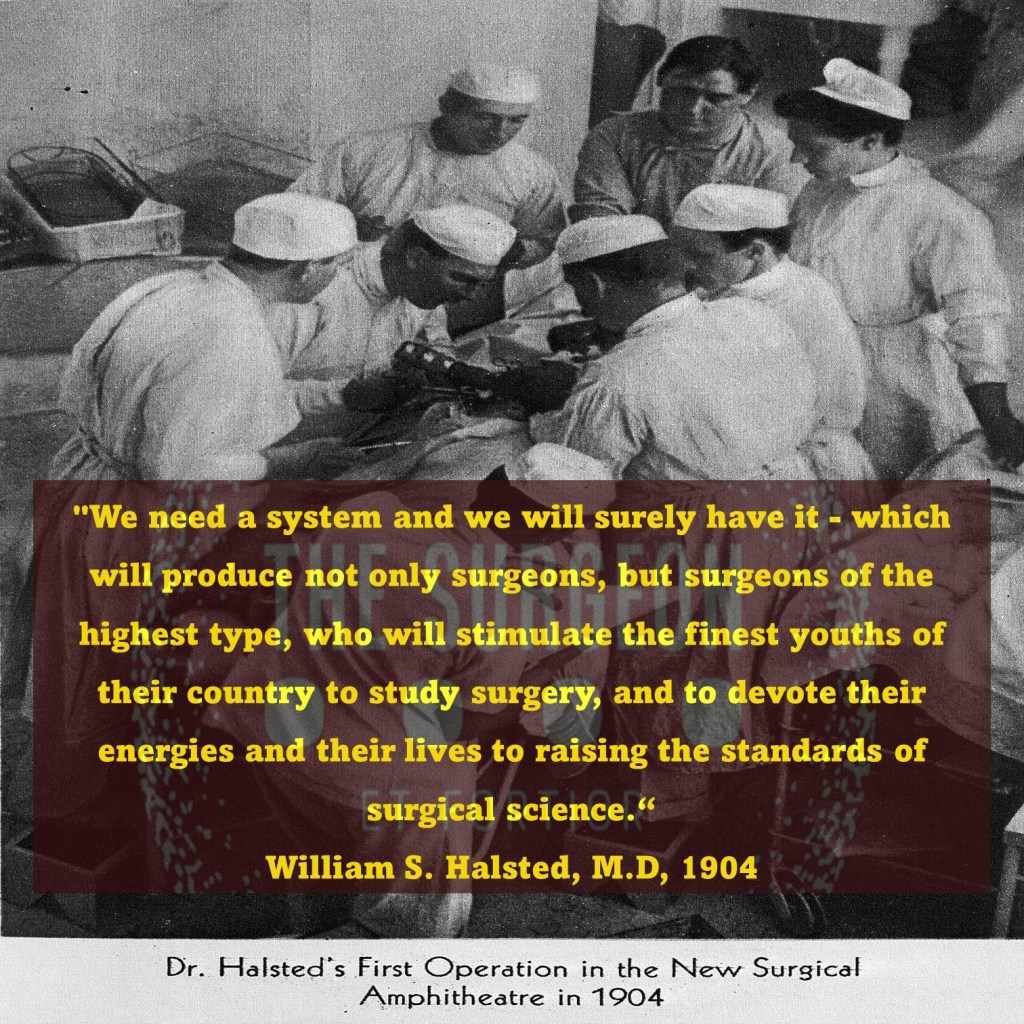

Legacy of Dr. William Stewart Halsted: Pioneer of Modern Surgery

In the annals of American surgery, the towering figure of Dr. William Stewart Halsted looms large, leaving an indelible mark on the field. Born in 1852 and educated at Andover and Yale, Halsted earned his medical degree from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City in 1878. His illustrious career unfolded against the backdrop of transformative contributions to surgery, earning him the title of the “father of modern surgery.”

Innovations and Contributions 🌟💡

Halsted’s impact reverberated across various realms of surgery. He played a pivotal role in introducing cocaine’s use as a topical anesthetic, revolutionizing the management of pain during surgical procedures. His contributions to the “radical cure” of inguinal hernia, deployment of Listerian principles to reduce wound infections significantly, and groundbreaking surgeries for conditions like gallbladder disease, thyroid disease, periampullary cancer, aneurysm, and breast cancer underscore his multifaceted brilliance.

Halsted Residency Program 🏥👨⚕️

Central to his legacy is the renowned Halsted residency program, which yielded 17 chief residents within 33 years. Dr. Gerald Imber’s biography, “Genius on the Edge: The Bizarre Double Life of Dr. William Stewart Halsted,” encapsulates the complexity of Halsted’s character—rigid yet nurturing, compulsive yet negligent, and always devoted to advancing surgical science.

Halsted’s Reflections and Critique 📜🤔

In a reflective address at Yale in 1904, Halsted acknowledged the transformative strides made in surgery, with pain, hemorrhage, and infection no longer posing insurmountable challenges. However, he voiced concerns about the state of medical education in the United States, advocating for a system that produces surgeons of the highest caliber. His critique emphasized the need for reforms unburdened by tradition, offering ample opportunities for comprehensive training.

Legacy Through Teaching and Training 👩⚕️📚

Following Halsted’s passing in 1922, Dr. Rudolph Matas extolled his greatness as a clinician, scientist, and founder of a surgical school that stood unparalleled in scholarship and achievement. Matas highlighted Halsted’s unique ability to select and nurture a cadre of surgeons who would carry forth his teachings and principles.

The Goal of Training the Next Generation 🌱👩⚕️

Matas, in emphasizing Halsted’s enduring impact, touched upon a lofty aspiration—to train the next generation of surgeons for excellence. Indeed, an active surgeon’s noble pursuit involves imparting knowledge, skills, and a commitment to advancing surgical science to successors.

There Are No Time-Outs: Surgeon’s Lifelong Commitment ⏰💪

The training of a surgeon spans a lengthy, intricate, and challenging path, yet it is undeniably rewarding. Dr. Thirlby’s sentiments, expressed in his Top Ten list, echo the pride associated with surgical accomplishments. The narrative takes a turn toward addressing the often-unspoken topics of work-life balance and burnout. Dr. Thirlby reflects on the countless instances where a surgeon, even when “off duty,” is called upon to employ medical skills and surgical expertise, underscoring the ever-present nature of a surgeon’s commitment to patient care.

In the world of surgery, the white coat symbolizes an unwavering commitment. Driven by a sense of duty, surgeons find themselves intervening in various settings—restaurants, airplanes, theaters, sports fields—always ready to respond. The poignant illustration, “Once you put on the white coat, there are no substitutions, there are no time outs,” encapsulates the profound truth that defines a surgeon’s lifelong dedication to healing and serving others. 🩺👨⚕️🌐

The Surgical Coach (P2)

Mastery in Surgery: The 10,000-Hour Rule

In his acclaimed book “Outliers: The Story of Success,” Malcolm Gladwell delves into the essence of mastery, drawing attention to the 10,000-hour rule popularized by neurologist Daniel Levitin. This rule posits that a staggering 10,000 hours of dedicated practice are requisite for achieving mastery and excellence in any domain. Gladwell surveys diverse fields, from composers and basketball players to fiction writers and surgeons, finding the recurrent thread of the 10,000-hour benchmark.

The Discrepancy in Surgical Training ⏰🔍

However, in the context of surgical training, a stark contrast emerges. Graduating surgical chief residents are tasked with documenting approximately 850 cases, far from the 10,000-hour milestone. Even when considering an estimated 2 hours per case, the cumulative hours fall significantly short. Coach Carril’s emphasis on teamwork, meticulous attention, and the importance of the present moment aligns with the concept of deliberate practice. In those 850 cases, residents are encouraged to focus on refining techniques and embracing each opportunity for skill development.

Teamwork, Basics, and Deliberate Practice 🤝📚

Coach Carril’s principles echo the necessity for teamwork and concentration on fundamental aspects, resonating with Gladwell’s insights. Carril’s principle #18, emphasizing the significance of the present task, aligns with the idea of deliberate practice—immersing oneself fully in the current learning experience. Residents, akin to basketball players honing their skills, find value in focused and intentional practice to bridge the training gap.

Surgery: The Satisfying Triad of Autonomy, Complexity, and Connection 🌐💼💡

Gladwell further posits three key attributes that render work satisfying for individuals: autonomy, complexity, and a tangible connection between effort and reward. Surgery, by its very nature, encapsulates these elements. Autonomy reigns in decision-making and procedural skills, complexity manifests in the intricate facets of various surgeries, and the connection between effort and reward is evident at both the patient and practitioner levels.

The Surgeon’s Reward: A Patient’s Survival and Personal Compensation 🏥💰

At the heart of surgical satisfaction lies the profound connection between the surgeon’s effort and the patient’s well-being. Successfully navigating complex scenarios can be a gratifying reward, epitomizing the essence of surgery. Moreover, the broader efforts of a surgeon, measured in operations performed and patients attended to, correlate with personal compensation and professional recognition.

As surgical training evolves, the delicate interplay between practice, teamwork, and the intrinsic rewards of surgery remains a cornerstone. The journey to mastery may not strictly adhere to the 10,000-hour rule, but the principles of deliberate practice, teamwork, and the fulfilling nature of surgical work persist as guiding beacons in the realm of surgery. 🌟🔪

The Surgical Coach (P1)

Surgery: A Symphony of Skill and Teamwork

In the intricate realm of surgery, where years of rigorous training shape the hands and minds of general surgeons, a profound truth emerges—surgery is not a solitary endeavor. The narrative transcends beyond the operating room, highlighting the symphony of professionals within the healthcare ecosystem. As the surgeon navigates the complexities of patient care, a collaborative effort ensues, akin to the harmonious workings of a team.

Training as a Crucible for Fundamentals 🎓⚙️

Enduring the arduous journey of medical school and a demanding surgical residency, a surgeon’s arsenal is forged. Knowledge, technical prowess, and stamina become the pillars, fortifying the foundation upon which surgical practice rests. Yet, the linchpin is teamwork, a realization that dawns upon every practitioner as they step into the intricate dance of healthcare delivery.

The Surgical Maestro: Pete Carril’s Wisdom 🏀📘

Drawing inspiration from an unexpected quarter, Coach Pete Carril, the luminary basketball coach at Princeton University, becomes a beacon of wisdom. Beyond the basketball court, Carril’s teachings encapsulate universal principles applicable to life and, surprisingly, surgery. In the succinct volume, “The Smart Take from the Strong,” co-authored with Dan White and introduced by the venerable Bobby Knight, Carril imparts timeless wisdom.

25 Little Things: A Paragon for Surgery and Life 🌐📜

Coach Carril’s “25 little things to remember” echo with relevance not just in the realm of basketball but resonate in the corridors of surgery and life. Delving into a few, such as “every little thing counts,” “you want to be good at those things that happen a lot,” and “the way you think affects what you see and do,” the parallels with surgery become strikingly apparent. Carril’s philosophy becomes a guide for surgeons, emphasizing the importance of attention to detail, practice, and the profound interplay between thought and action.

Beyond the Hardwood: Surgery as a Team Sport 🤝🔬

In a synchrony reminiscent of a basketball team, the surgeon harmonizes with a chorus of healthcare professionals—nurses, anesthesiologists, support staff, administrators, and more. The cadence of success is dictated not just by individual skill but by the collective effort of the team. Vision, anticipation, and unwavering dedication converge, not only on the basketball court but also in the theater of surgery.

As Coach Carril remains a silent spectator in the hallowed halls of Princeton, witnessing a new generation striving for victory, surgeons too find inspiration in the collective pursuit of excellence. Teamwork, an indomitable spirit, and a commitment to personal and collective growth emerge as the hallmarks of success, both on the hardwood and in the operating room. 🏀🌟🔪

The Surgical Coach

Surgical Wisdom Unveiled: A Top Ten List and Commandments

Reflections on a Surgical Journey 🌟

Life’s journey is a mosaic woven with threads of guidance from parents, siblings, and mentors. This chapter transcends the mundane, embracing philosophy and personal testimony on sculpting a triumphant surgical career. Dr. Richard C. Thirlby, in the spirit of David Letterman, unfurls a top ten list that serves as a compass for aspiring surgeons.

Dr. Thirlby’s Top Ten Surgical Tenets 📜🌐

- Training is Fun (You’ll Never Forget It): A nod to lifelong learning, acknowledging the perpetual metamorphosis in surgical careers.

- Job Security: General surgeons, vital and in demand, find positions across diverse landscapes, from bustling urban centers to the serene rural expanses.

- The Pay is Not Bad: Comfortable compensation, soaring above societal averages, promises financial stability.

- Your Mother Will Be Proud of You: A familial pride resonates, extending beyond mothers to fathers, aunts, and a tapestry of family members.

- Surgeons Have Panache: Embracing the surgical personality and the unique culture that envelopes surgical realms.

- You Will Have Heroes; You Will Be a Hero: Surgeons, sculpted by influencers, reciprocate by becoming beacons of hope for grateful patients.

- There is Spirituality if You Want It: The inexplicable recoveries, the miraculous moments that defy statistical norms.

- You Will Change Patients’ Lives: A profound personal satisfaction derived from the tangible impact on patients’ destinies.

- Patients Will Change Your Life: Daily lessons from patients foster humility, nonjudgmentalism, and a continuous journey towards becoming a better human being.

- I Love to Cut: A poetic reflection of the joy derived from the meticulous artistry of surgical procedures, executed with precision for the greater good.

The Commandments of Surgical Living 🌌📜

Adding depth to the narrative, akin to timeless commandments, Dr. James D. Hardy contributes a list transcending millennia, etched in the New King James Version of the Holy Bible.

- Know Your Higher Power: An homage to the spiritual facet of life and the sanctity of the Sabbath day.

- Respect Your Roots: An acknowledgment of the significance of parents and the importance of familial bonds.

- Do No Harm: An ancient ethos resonates through the prohibition of actions such as murder, adultery, theft, lying, and coveting others’ belongings.

- Strive for Excellence: An unending pursuit of personal and professional growth, embodying efficiency, excellence, and the preservation of integrity.

- Prepare for Leadership: A call to groom leaders, emphasizing the importance of educational and professional growth.

- Nourish Professional Relationships: Recognizing the value of mentors, preserving the wisdom passed down through generations.

- Remember Your Roots: An echo from Dr. Hardy’s personal ten commandments, urging individuals to honor their origin and represent it with pride.

- Cherish Family: A gentle reminder to spend quality time with family, recognizing the profound impact of love on children.

- Spend Time Alone: Advocating for moments of solitude, fostering creative thinking and personal reflection.

- Find Joy in Your Work: A profound truth encapsulated in the sustenance derived from the daily pursuit of meaningful work one genuinely enjoys.

In this amalgamation of Dr. Thirlby’s top ten and Dr. Hardy’s commandments, a roadmap unfolds — a guide not just for a surgical career but for a fulfilling and purpose-driven life. 🌈🔍🔬

Gastrointestinal Anastomosis

Navigating the Gastrointestinal Anastomosis: A Surgical Odyssey

Unveiling the Historical Tapestry 🕰️

The creation of gastrointestinal anastomoses, an art in general surgery, has evolved over centuries. In delving into this surgical saga, fundamental principles stand tall, guiding the surgeon’s hands. This chapter unfolds the historical nuances, general tenets for successful anastomosis creation, and delves into pivotal technical considerations amidst current controversies.

The Dance of Healing and Anatomy 🩹🔍

Understanding the physiological waltz of gastrointestinal wound healing and the intricacies of intestinal wall anatomy sets the stage. An enterotomy’s inception triggers a symphony of vasoconstriction, vasodilation, and capillary changes, orchestrating the ballet of tissue healing. Granulation tissue emerges, heralding the proliferative phase, where collagen undergoes a dance of lysis and synthesis.

Layers of the Gastrointestinal Tapestry 🧵

The intestinal wall, a multilayered tapestry, unravels its secrets. The serosa, a connective tissue cloak veiled by mesothelial lining, demands precise apposition to thwart leakage risks. The submucosa, the stronghold of tensile strength, anchors the sutures knitting the anastomosis. Intestinal mucosa seals the deal, driven by epithelial cell migration and hyperplasia, crafting a watertight barrier.

Local Factors: Paving the Path to Healing ⚒️🩹

The local factors influencing this symphony include intrinsic blood supply and tension management. Adequate blood supply, a lifeline for tissue oxygenation, hinges on meticulous surgical technique. Tension, a delicate partner in this dance, demands finesse; too much jeopardizes perfusion, too little invites inflammatory infiltrates. The colon, in particular, demands a surgeon’s nuanced touch.

Systemic Harmony: The Ripples of Patient Factors 🔄🌊

Systemic factors contribute their ripples to this surgical pond. Hypotension, hypovolemia, and sepsis compose a dissonant note affecting blood flow and oxygen delivery. Patient-specific variables — malnutrition, immunosuppression, and medication use (hello, steroids and NSAIDs) — compose a subplot, influencing the narrative of wound healing.

As the surgeon steps into this intricate ballet of anastomosis creation, history, physiology, and patient-specific factors converge. Each suture, each decision, shapes the narrative of healing. The gastrointestinal odyssey continues, blending tradition with innovation, as surgeons embark on the timeless quest for successful anastomoses. 🌐🔍🩺

Pre Surgical Evaluation of BLEEDING

Unraveling Bleeding Risks: A Surgical Odyssey

In the realm of surgical care, meticulous assessment of bleeding risk is paramount. The age of onset of bleeding and the specific sites affected offer crucial clues, helping differentiate between inherited and acquired bleeding disorders. Inherited disorders, often manifesting in childhood, may lurk beneath the surface, surfacing during surgical trauma in adulthood.

Decoding the History 🕰️

Interrogating the patient’s history unveils key insights. Medication usage, both prescription and over-the-counter, unfurls potential contributors to bleeding events. Family history provides a roadmap for inheritance patterns, crucial in diagnosing disorders like hemophilia. The severity of past bleeding incidents serves as a yardstick, guiding expectations during surgical challenges. Comorbidities, especially liver and kidney dysfunction, loom large in magnifying bleeding risks.

The Physical Symphony 🩺🎶

While the physical exam plays a supportive role, it may hint at platelet disorders through findings like petechiae and ecchymoses. Platelet function issues or deficiencies may manifest similarly, emphasizing the importance of a comprehensive history. Single-site bleeding tends to be non-indicative of a bleeding disorder, while multisite bleeding raises red flags.

Laboratory Pilgrimage 🧪

A pilgrimage through laboratory tests offers a comprehensive snapshot of hemostatic competence. Assessing platelet count, complete blood count (CBC), platelet function, aPTT, PT, and fibrinogen levels becomes the map for surgical decisions.

Unmasking Causes of Excessive Surgical Bleeding 🚩

Most patients enter the operating room with normal hemostasis. However, certain surgeries, like liver transplants or trauma interventions, may trigger consumptive coagulopathy. Preexisting hemostatic defects, especially congenital bleeding disorders like hemophilia and von Willebrand disease, require keen suspicion.

Hunting the Culprit: Acquired Bleeding Disorders 🎯

Liver disease emerges as a common instigator of coagulation abnormalities, while anticoagulant therapies like Coumadin and heparin cast shadows on surgical hemostasis. Acquired thrombocytopenia, often linked to splenomegaly or medications, and platelet function disorders, especially induced by aspirin and clopidogrel, populate the landscape of surgical challenges.

Navigating Intraoperative Waters ⚓🔍

Intraoperative bleeding may cascade from shock, massive transfusions, or acute hemolytic reactions. Hemostatic agents, from gelatin sponge to topical thrombin, stand as stalwart navigators through these turbulent waters.

Postoperative Chessboard: A Risky Endgame ♟️🩹

Postoperative bleeding, often stemming from inadequate hemostasis, unveils additional players. Residual heparin, altered liver function, and acquired clotting factor deficiencies post-hepatectomy amplify the stakes. Fibrinolysis disorders may also cast shadows post-surgery.

Dancing with Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) 🩸🎭

DIC, a theatrical presentation of intravascular coagulation gone awry, demands a spot on the stage. Prompt recognition and addressing precipitating factors are pivotal, with cryoprecipitate and platelet transfusions standing as protagonists.

Fibrinolytic Fantasia: When Clotting Goes Amiss 🌪️🩹

Primary and secondary fibrinolysis emerge as culprits in postsurgical bleeding, often linked to lytic therapy, severe liver failure, or DIC. Managing fibrinolytic storms necessitates tailored interventions.

Hypercoagulable Waltz in Surgical Limelight 💃🕺

A careful dance with thromboembolism risks follows, accentuating the importance of patient history in unraveling congenital and acquired hypercoagulable states. A familial narrative often unravels the genetic predispositions steering this intricate choreography.

In the surgical arena, every patient’s hemostatic tale unfolds uniquely. Through history, examination, and laboratory revelations, surgeons navigate the delicate balance between bleeding and clotting, ensuring a symphony of healing amidst the surgical odyssey. 🌐🔍🩺

Nutritional Surgical Care

Navigating the Nutritional Maze in Surgical Care 🌐🔍

Surgeons bear the responsibility of caring for patients whose nutritional status may be compromised, influencing their ability to heal optimally. The challenges encompass an array of issues, including anorexia, inanition, gluconeogenesis acceleration, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and electrolyte and hormonal imbalances. These factors intricately impact surgical responses and a patient’s healing capacity. Let’s delve into the complex world of digestive tract, esophageal, gastric, intestinal, and other surgeries, exploring how they interplay with nutritional considerations.

Digestive Tract Surgery 🍽️

The digestive tract, a bustling center of metabolic activity, plays a pivotal role in nutrient digestion, absorption, and metabolism. Surgical interventions involving the gastrointestinal (GI) tract can lead to malabsorption and maldigestion, causing nutritional deficiencies. Understanding the site of nutrient absorption aids in identifying potential postoperative deficiencies. Enhancing nutritional status before surgery becomes crucial for a smoother postoperative recovery.

Esophageal Surgery 🥄

Various conditions affecting the esophagus, from corrosive injuries to obstruction, necessitate surgical intervention. Procedures involve replacing the esophagus with the stomach or intestine, each carrying unique considerations. Nutritional support, including nasoenteric feeding tubes or parenteral nutrition (PN), may be necessary preoperatively for obstructed esophagi, with additional intraoperative measures for optimal postoperative outcomes.

Gastric Surgery 🥢

Gastric surgical procedures, while addressing specific issues, can potentially lead to malnutrition. Patients may experience dumping syndrome, requiring dietary modifications and cautious fluid intake. Anemia and metabolic bone diseases are common consequences, demanding periodic injections and calcium-vitamin D supplementation. Understanding postgastrectomy dietary modifications and careful fluid management becomes paramount.

Intestinal Surgery 🍴

Resection of excessive lengths of the intestine, especially in short bowel syndrome, can result in severe malabsorption and malnutrition. Long-term PN might be necessary to maintain nutritional balance. Pancreaticoduodenectomy, a complex surgery, requires postoperative monitoring for complications like delayed gastric emptying, diabetes mellitus, and malabsorption, influencing nutrient guidelines.

Ileostomy and Colostomy 🚽

Procedures like ileostomy or colostomy, creating artificial anuses, are employed for various intestinal issues. Patients with ostomies generally follow regular diets, with adjustments based on stoma output. High-output ostomies necessitate specific dietary precautions to manage fluid levels. Nutritional assessment’s crucial role in surgical outcomes emphasizes the growing interest in tailored preoperative nutritional support and the potential resurgence of parenteral nutrition.

Conclusion 🩺💡

Understanding the intricate dance between surgical interventions and nutritional considerations is paramount for surgeons and medical practitioners. As regulatory scrutiny intensifies, the role of nutrition in preventing complications and improving outcomes will likely take center stage, emphasizing the importance of personalized nutritional strategies in the surgical journey. 🌟💪

Tubes and Drains

Unlocking the World of Tubes and Drains in Medical Practice 🩹

Understanding the diverse array of tubes and drains is crucial for any medical practitioner, and it all begins with appreciating the French size system, where the outer diameter of a catheter is denoted. A quick calculation (French size multiplied by 0.33) reveals the catheter’s outer diameter in millimeters.

Gastrointestinal Tract Tubes 🍽️

Starting with nasogastric tubes designed to evacuate gastric contents, these are frequently employed in patients facing ileus or obstruction. Modern nasogastric tubes often incorporate a sump function, preventing suction locks and enhancing efficiency. Nonsump tubes, though less common, may be used for intermittent suction. Nasogastric tubes also serve in feeding, with soft, fine-bore tubes being preferred for this purpose. Nasoenteric tubes, intended for feeding, require careful attention to safety during instillation.

Nasobiliary tubes, often placed endoscopically, aid in biliary drainage in cases of obstruction or fistula. T-tubes within the common bile duct ensure closed gravity drainage. Gastrostomy tubes, placed surgically or via percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), find utility in drainage or feeding. Jejunostomy tubes, inserted surgically or endoscopically, are vital for long-term nutritional access.

Respiratory Tract Tubes 🫁

Chest tubes play a pivotal role in pleural cavity drainage, addressing issues like pneumothorax, hemothorax, or effusion. The three-bottle system facilitates constant suction, drainage, and prevention of air entry, crucial for maintaining a water seal.

Endotracheal tubes, cuffed for a secure tracheal seal, cater to short-term mechanical ventilation needs in adults. Tracheotomy tubes, directly inserted into the trachea through the neck, become essential for prolonged mechanical ventilation or when maintaining a patent airway is challenging.

Urinary Tract Tubes 🚰

Bladder catheters, commonly known as “Foley” catheters, serve to straight drain urine. Nephrostomy tubes, placed in the renal pelvis, drain urine above obstructions or delicate ureteral anastomoses. Percutaneously placed tubes, often pigtail catheters, assist in draining abscesses, typically guided by interventional radiologists.

Surgical Drains 🌡️

Closed suction drains, such as Jackson-Pratt and Hemovac, prove invaluable for evacuating fluid collections during surgery. Sump suction drains, like Davol drains, are larger and designed for continuous suction in scenarios with thick or particulate drainage. Passive tubes, exemplified by Penrose drains, offer a pathway for fluid without applied suction, serving as a two-way conduit for bacteria. Understanding these various tubes and drains is pivotal for medical practitioners navigating complex clinical scenarios. 💉💊

The Geriatric Patient

Navigating Surgical Challenges in an Aging Population: A Delicate Balance 🌐

The ongoing aging process within the American population brings forth a set of unique challenges that surgeons must adeptly navigate for decades to come. Elderly individuals, compared to their younger counterparts, often exhibit diminished physiological reserves. Their health is frequently influenced by medications that can alter normal physiological responses, such as β-blockers, or impact surgical outcomes, like warfarin or platelet aggregation–inhibiting agents. Additionally, baseline impairments, ranging from sensory issues to difficulties in ambulation or dementia, may complicate their ability to engage in everyday activities.

One perplexing dilemma faced by surgeons when caring for elderly patients revolves around the decision to pursue an aggressive intervention plan. Transparent communication between the patient and physician is paramount in determining the appropriate level of aggressiveness in the patient’s best interest. This conversation takes on heightened significance in the elderly population. Engaging in repeated discussions with patients and their families, starting before surgery and extending into the postoperative phase, is crucial. Generally, patients express a desire for aggressive medical care as long as there remains a reasonable chance for meaningful survival.

While these discussions may be uncomfortable, they are as integral to the patient’s care as any aspect of their medical history. It is imperative to recognize that surgical care is provided by individuals who genuinely care about the patient’s overall well-being. In certain situations, medical care may prioritize alleviating pain over prolonging life. Ideally, these conversations should occur in a serene and comfortable setting, free from distractions.

Moreover, it is essential to underscore that discussions about end-of-life matters are not legal proceedings. No forms need to be signed. These discussions are akin to any other conversation between a doctor and a patient regarding their care. The dialogue involves a careful consideration of the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches until a collaborative plan of action is determined. The only distinction lies in the profound nature of end-of-life discussions, offering patients the best opportunity to shape their destinies. Consequently, these discussions should be approached with the utmost reverence, acknowledging the gravity of the subject matter. 🤝💙

Estabelecendo Conexões Essenciais 💬

Técnicas de Entrevista na Medicina: Estabelecendo Conexões Essenciais 💬