Surgeons and Performance

SURGEONS ARE HIGH PERFORMANCE ATHLETES

In a 2011 New Yorker article, Dr. Atul Gawande explored the idea that surgeons should consider a performance coach. Like athletes, he reasons, surgeons rely on complex physical movements to achieve their goals. Guidance and refinement by a trained eye could improve their performance.

Surgical coaching is a controversial topic (one which colleagues and I are actively investigating). But in the years following Dr. Gawande’s article, this idea opened the door to a broader concept: the “surgeon athlete.” An “athlete” is one whose performance depends on a carefully choreographed interplay between mind and body: heightened focus and anticipation along with quick decision-making and coordination. Combined with the reliance on teamwork and requisite stamina, this is wholly within the job description of a surgeon. Many surgeons are likely to find this concept silly. But our profession has imprudently encouraged surgical trainees to disregard the critical fine-tuning of their minds and bodies. We demand perfection, stamina, and encyclopedic knowledge, while discouraging the healthy habits that improve performance. Ironically, the sports world is more advanced in applying science to their training. And by ignoring this indisputable science, we are really hurting our patients. Because in order to best take care of them, we need to first take care of ourselves.

Hepatic Surgery: Portal Vein Embolization

INTRODUCTION

Portal vein Embolizations (PVE) is commonly used in the patients requiring extensive liver resection but have insufficient Future Liver Remanescent (FLR) volume on preoperative testing. The procedure involves occluding portal venous flow to the side of the liver with the lesion thereby redirecting portal flow to the contralateral side, in an attempt to cause hypertrophy and increase the volume of the FLR prior to hepatectomy.

PVE was first described by Kinoshita and later reported by Makuuchi as a technique to facilitate hepatic resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. The technique is now widely used by surgeons all over the world to optimize FLR volume before major liver resections.

PHYSIOPATHOLOGY

PVE works because the extrahepatic factors that induce liver hypertrophy are carried primarily by the portal vein and not the hepatic artery. The increase in FLR size seen after PVE is due to both clonal expansion and cellular hypertrophy, and the extent of post-embolization liver growth is generally proportional to the degree of portal flow diversion. The mechanism of liver regeneration after PVE is a complex phenomenon and is not fully understood. Although the exact trigger of liver regeneration remains unknown, several studies have identified periportal inflammation in the embolized liver as an important predictor of liver regeneration.

THECNICAL ASPECTS

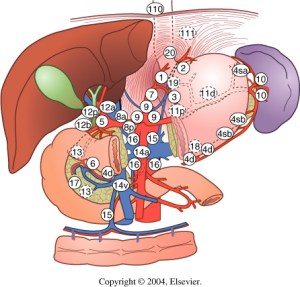

PVE is technically feasible in 99% of the patients with low risk of complications. Studies have shown the FLR to increase by a median of 40–62% after a median of 34–37 days after PVE, and 72.2–80% of the patients are able to undergo resection as planned. It is generally indicated for patients being considered for right or extended right hepatectomy in the setting of a relatively small FLR. It is rarely required before extended left hepatectomy or left trisectionectomy, since the right posterior section (segments 6 and 7) comprises about 30% of total liver volume.

PVE is usually performed through percutaneous transhepatic access to the portal venous system, but there is considerable variability in technique between centers. The access route can be ipsilateral (portal access at the same side being resected) with retrograde embolization or contralateral (portal access through FLR) with antegrade embolization. The type of approach selected depends on a number of factors including operator preference, anatomic variability, type of resection planned, extent of embolization, and type of embolic agent used. Many authors prefer ipsilateral approach especially for right-sided tumors as this technique allows easy catheterization of segment 4 branches when they must be embolized and also minimizes the theoretic risk of injuring the FLR vasculature or bile ducts through a contralateral approach and potentially making a patient ineligible for surgery.

However, majority of the studies on contralateral PVE show it to be a safe technique with low complication rate. Di Stefano et al. reported a large series of contralateral PVE in 188 patients and described 12 complications (6.4%) only 6 of which could be related to access route and none precluded liver resection. Site of portal vein access can also change depending on the choice of embolic material selected which can include glue, Gelfoam, n-butyl-cyanoacrylate (NBC), different types and sizes of beads, alcohol, and nitinol plus. All agents have similar efficacy and there are no official recommendations for a particular type of agent.

RESULTS

Proponents of PVE believe that there should be very little or no tumor progression during the 4–6 week wait period for regeneration after PVE. Rapid growth of the FLR can be expected within the first 3–4 weeks after PVE and can continue till 6–8 weeks. Results from multiple studies suggest that 8–30% hypertrophy over 2–6 weeks can be expected with slower rates in cirrhotic patients. Most studies comparing outcomes after major hepatectomy with and without preoperative PVE report superior outcomes with PVE. Farges et al. demonstrated significantly less risk of postoperative complications, duration of intensive care unit, and hospital stay in patients with cirrhosis who underwent right hepatectomy after PVE compared to those who did not have preoperative PVE. The authors also reported no benefit of PVE in patients with a normal liver and FLR >30%. Abulkhir et al. reported results from a meta-analysis of 1088 patients undergoing PVE and showed a markedly lower incidence of Post Hepatectomy Liver Failure (PHLF) and death compared to series reporting outcomes after major hepatectomy in patients who did not undergo PVE. All patients had FLR volume increase, and 85% went on to have liver resection after PVE with a PHLF incidence of 2.5% and a surgical mortality of 0.8%. Several studies looking at the effect of systemic neoadjuvant chemotherapy on the degree of hypertrophy after PVE show no significant impact on liver regeneration and growth.

VOLUMETRIC RESPONSE

The volumetric response to PVE is also a very important factor in understanding the regenerative capacity of a patient’s liver and when used together with FLR volume can help identify patients at risk of poor postsurgical outcome. Ribero et al. demonstrated that the risk of PHLF was significantly higher not only in patients with FLR ≤ 20% but also in patients with normal liver who demonstrated ≤5% of FLR hypertrophy after PVE. The authors concluded that the degree of hypertrophy >10% in patients with severe underlying liver disease and >5% in patients with normal liver predicts a low risk of PHLF and post-resection mortality. Many authors do not routinely offer resection to patients with borderline FLR who demonstrate ≤5% hypertrophy after PVE.

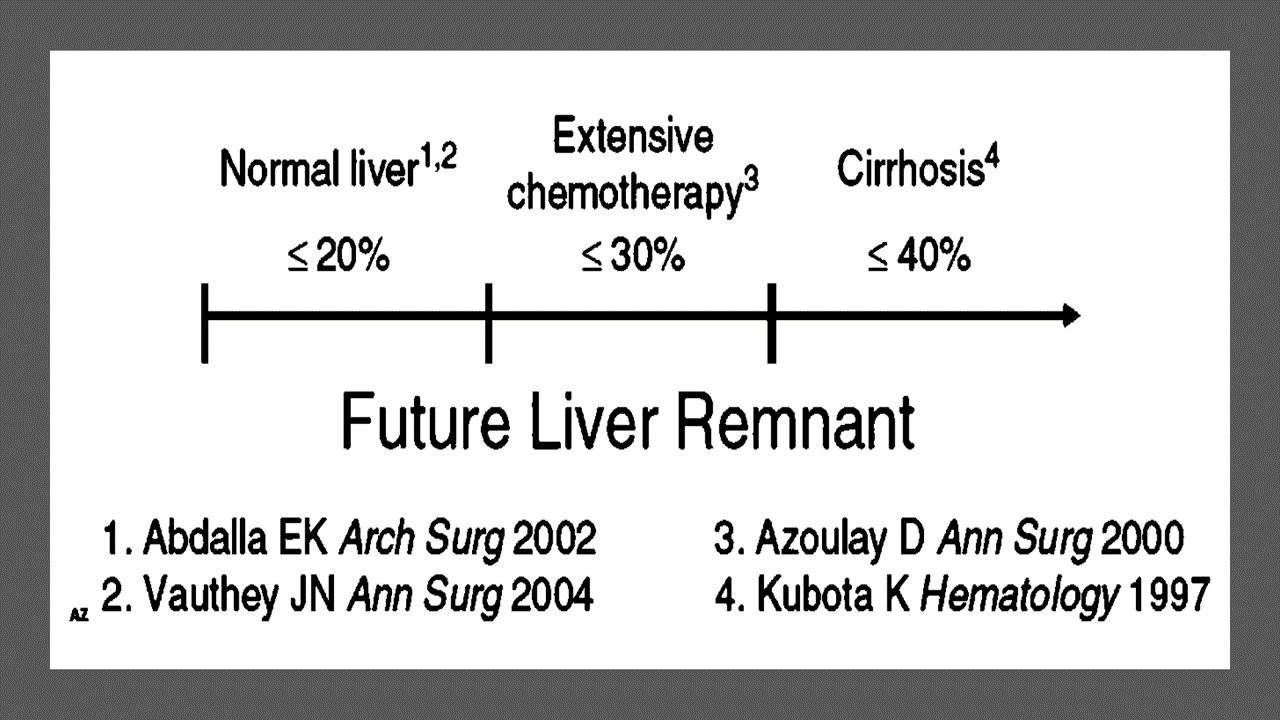

Predicting LIVER REMNANT Function

Careful analysis of outcome based on liver remnant volume stratified by underlying liver disease has led to recommendations regarding the safe limits of resection. The liver remnant to be left after resection is termed the future liver remnant (FLR). For patients with normal underlying liver, complications, extended hospital stay, admission to the intensive care unit, and hepatic insufficiency are rare when the standardized FLR is >20% of the TLV. For patients with tumor-related cholestasis or marked underlying liver disease, a 40% liver remnant is necessary to avoid cholestasis, fluid retention, and liver failure. Among patients who have been treated with preoperative systemic chemotherapy for more than 12 weeks, FLR >30% reduces the rate of postoperative liver insufficiency and subsequent mortality.

When the liver remnant is normal or has only mild disease, the volume of liver remnant can be measured directly and accurately with threedimensional computed tomography (CT) volumetry. However, inaccuracy may arise because the liver to be resected is often diseased, particularly in patients with cirrhosis or biliary obstruction. When multiple or large tumors occupy a large volume of the liver to be resected, subtracting tumor volumes from liver volume further decreases accuracy of CT volumetry. The calculated TLV, which has been derived from the association between body surface area (BSA) and liver size, provides a standard estimate of the TLV. The following formula is used:

TLV (cm3) = –794.41 + 1267.28 × BSA (square meters)

Thus, the standardized FLR (sFLR) volume calculation uses the measured FLR volume from CT volumetry as the numerator and the calculated TLV as the denominator: Standardized FLR (sFLR) = measured FLR volume/TLV Calculating the standardized TLV corrects the actual liver volume to the individual patient’s size and provides an individualized estimate of that patient’s postresection liver function. In the event of an inadequate FLR prior to major hepatectomy, preoperative liver preparation may include portal vein embolization (PVE).

Classroom: Principles of Hepatic Surgery

Surgical Management of Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a rare but lethal cancer arising from the bile duct epithelium. As a whole, CCA accounts for approximately 3 % of all gastrointestinal cancers. It is an aggressive disease with a high mortality rate. Unfortunately, a significant proportion of patients with CCA present with either unresectable or metastatic disease. In a retrospective review of 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma, Jarnagin et al. reported that 29 % of patients had either unresectable disease were unfit for surgery. Curative resection offers the best chance for longterm survival. Whereas palliation with surgical bypass was once the preferred surgical procedure even for resectable disease, aggressive surgical resection is now the standard.

Classroom: Surgical Management of Cholangiocarcinoma

Minimally Invasive Approach to Choledocholithiasis

Introduction

The incidence of choledocholithiasis in patients undergoing cholecystectomy is estimated to be 10 %. The presence of common bile duct stones is associated with several known complications including cholangitis, gallstone pancreatitis, obstructive jaundice, and hepatic abscess. Making the diagnosis early and prompt management is crucial. Traditionally, when choledocholithiasis is identified with intraoperative cholangiography during the cholecystectomy, it has been managed surgically by open choledochotomy and place- ment of a T-tube. This open surgical approach has a morbidity rate of 10–15 %, mortality rate of <1 %, with a <6 % incidence of retained stones. Patients who fail endoscopic retrieval of CBD stones, as well as cases in which an endoscopic approach is not appropriate, should be explored surgically.

Clinical Manifestation

Acute obstruction of the bile duct by a stone causes a rapid distension of the biliary tree and activation of local pain fibers. Pain is the most common presenting symptom for choledocholithiasis and is localized to either the right upper quadrant or to the epigastrium. The obstruction will also cause bile stasis which is a risk factor for bacterial over- growth. The bacteria may originate from the duodenum or the stone itself. The combination of biliary obstruction and colo- nization of the biliary tree will lead to the development of fevers, the second most common presenting symptom of cho- ledocholithiasis. Biliary obstruction, if unrelieved, will lead to jaundice. When these three symptoms (pain, fever, and jaundice) are found simultaneously, it is known as Charcot’s triad. This triad suggests the diagnosis of acute ascending cholangitis, a potentially life-threatening condition. If not treated promptly, this can lead to hypotension and decreased metal status, both signs of severe sepsis. When combined with Charcot’s triad, this constellation of symptoms is commonly referred to as Reynolds pentad.

Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration

Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) allows for single stage treatment of gallstone disease, reducing overall hospital stay, improving safety and cost-effectiveness when compared to the two-stage approach of ERCP and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Bile duct clearance can be confirmed by direct visualization with a choledochoscope. But, before the advent of choledochoscope, bile duct clearance was uncertain, and blind instrumentation of the duct resulted in accentuated edema and inflammation. Due to advancement in instruments, optical magnification, and direct visualization, laparoscopic exploration of the CBD results in fewer traumas to the bile duct. This has led to an increasing tendency to close the duct primarily, reducing the need for placement of T-tubes. Still, laparoscopic bile duct exploration is being done in only a few centers. Apart from the need for special instruments, there is also a significant learning curve to acquire expertise to be able to perform a laparoscopic bile duct surgery.

Morbidity and mortality rates of laparoscopic exploration are comparable to ERCP (2–17 and 1–5 %), and there is no clear difference in primary success rates between the two approaches. However, the endoscopic approach may be preferable for elderly and frail patients, who are at higher risk with surgery. Patients older than 70–80 years of age have a 4–10 % mortality rate with open duct exploration. It may be as high as 20 % in elderly patients undergoing urgent procedures. In comparison, advanced age and comor- bidities do not have a significant impact on overall complication rates for ERCP. A success rate of over 90 % has been reported with laparoscopic CBD exploration. Availability of surgical expertise and appropriate equipment affect the success rate of laparoscopic exploration, as does the size, number of the CBD stones, as well as biliary anatomy. Over the years, laparoscopic exploration has become efficient, safe, and cost effective. Complications include CBD laceration, stricture formation, bile leak, abscess, pancreatitis, and retained stones.

In cases of failure of laparoscopic CBD exploration, a guidewire or stent can be passed through the cystic duct, common bile duct, and through the ampulla into the duodenum followed by cholecystectomy. This makes the identification and cannulation of the ampulla easier during the post- operative ERCP. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration is traditionally performed through a transcystic or transductal approach. The transcystic approach is appropriate under certain circumstances. These include a small stone (<10 mm) located in the CBD, presence of small common bile duct (<6 mm), or if there is poor access to the common duct. The transductal approach is preferable in cases of large stones, stones in proximal ducts (hepatic ducts), large occluding stones in a large duct, presence of multiple stones, or if the cystic duct is small (<4 mm) or tortuous. Contraindications for laparoscopic approach include lack of training, and severe inflammation in the porta hepatis making the exploration difficult and risky.

Key Points

With advancement in imaging technology, laparoscopic and endoscopic techniques, management of common bile duct stone has changed drasti- cally in recent years. This has made the treatment of this condition safe and more efficient. Many options are now available to manage this condition, and any particular modality for treatment should be chosen carefully based on the patient related factors, institutional protocol, available expertise, resources, and cost-effectiveness.

Classroom: M.I.A. of Choledocholithiasis

IPMN Surgical Management

INTRODUCTION

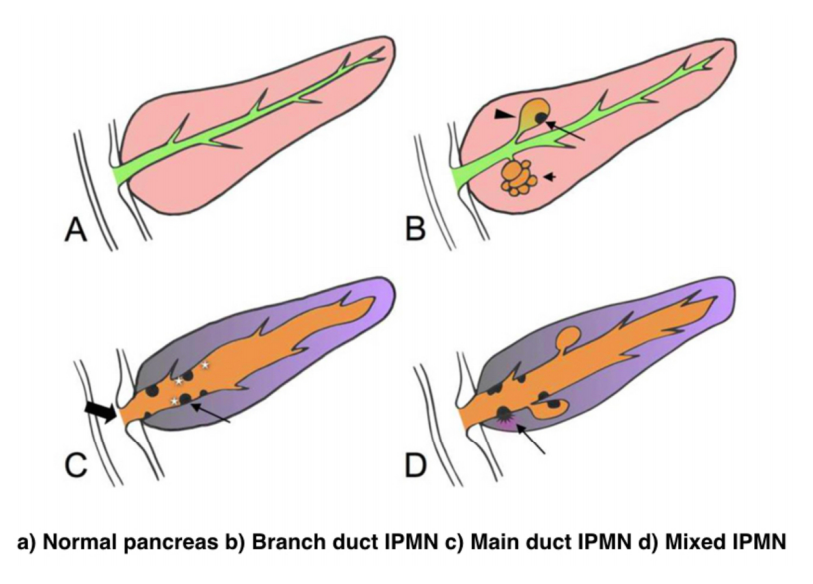

IPMNs were first recognized in 1982 by Ohashi, but the term IPMN was not officially used until 1993. IPMNs are defined in the WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System as an intraductal, grossly visible epithelial neoplasm of mucin-producing cells. Using imaging and histology, IPMNs can be classified into three types based on duct involvement:

1. Main-duct IPMN (approximately 25% of IPMNs): Segmental or diffuse dilation of the main pancreatic duct (>5 mm) in the absence of other causes of ductal obstruction.

2. Branch-duct IPMN (approximately 57% of IPMNs): Pancreatic cysts (>5 mm) that communicate with the main pancreatic duct.

3. Mixed type IPMN (approximately 18% of IPMNs): Meets criteria for both main and branch duct.

Due to the asymptomatic nature of the disease, the overall incidence of IPMNs is difficult to define but is thought to account for approximately 3% to 5% of all pancreatic tumors. Most IPMNs are discovered as incidental lesions from the workup of an unrelated process by imaging or endoscopy. IPMNs are slightly more prevalent in males than in females, with a peak incidence of 60 to 70 years of age. Branch-duct IPMNs tend to occur in a slightly younger population and are less associated with malignancy compared with main-duct or mixed variants.

Because a majority of IPMNs are discovered incidentally, most are asymptomatic. When symptoms do occur, they tend to be nonspecific and include unexplained weight loss, anorexia, abdominal pain, and back pain. Jaundice can occur with mucin obstructing the ampulla or with an underlying invasive carcinoma. The obstruction of the pancreatic duct can also lead to pancreatitis. IPMNs may represent genomic instability of the entire pancreas. This concept, known as a “field defect,” has been described as a theoretical risk of developing a recurrent IPMN or pancreatic adenocarcinoma at a site remote from the original IPMN. The three different types of IPMNs, main duct, branch duct, and mixed duct, dictate different treatment algorithms.

MAIN DUCT IPMNs

Main-duct IPMNs should be resected in all patients unless the risks of existing comorbidities outweigh the benefits of resection. The goal of operative management of IPMNs is to remove all adenomatous or potentially malignant epithelium to minimize recurrence in the pancreas remnant. There are two theories on the pathophysiologic basis of IPMNs. The first groups IPMNs into a similar category as an adenocarcinoma, a localized process involving only a particular segment of the pancreas. The thought is that removal of the IPMN is the only treatment necessary. In contrast, some believe IPMNs to represent a field defect of the pancreas. All of the ductal epithelium remains at risk of malignant degeneration despite removal of the cyst. Ideally, a total pancreatectomy would eliminate all risk, but this is a radical procedure that is associated with metabolic derangements and exocrine insufficiency. Total pancreatectomy should be limited to the most fit patients, with a thorough preoperative assessment and proper risk stratification prior to undertaking this surgery.

There is less uncertainty with treatment of main-duct IPMNs. The high incidence of underlying malignancy associated with the IPMNs warrants surgical resection. IPMNs localized to the body and tail (approximately 33%) can undergo a distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy. At the time of surgery, a frozen section of the proximal margin should be interpreted by a pathologist to rule out high-grade dysplasia. A prospective study identified a concordance rate of 94% between frozen section and final pathologic examination. If the margin is positive (high-grade dysplasia, invasion) additional margins may be resected from the pancreas until no evidence of disease is present. However, most surgeons will proceed to a total pancreatectomy after two subsequent margins demonstrate malignant changes. This more extensive procedure should be discussed with the patient prior to surgery, and the patient should be properly consented regarding the risks of a total pancreatectomy.

IPMNs localized to the head or uncinate process of the pancreas should undergo a pancreaticoduodenectomy. A frozen section of the distal margin should be analyzed by pathology for evidence of disease. As mentioned before, after two additional margins reveal malignant changes, a total pancreatectomy is usually indicated (approximately 5%). The absence of abnormal changes in frozen sections does not equate to negative disease throughout the pancreas remnant. Rather, skip lesions involving the remainder of the pancreas can exist and thus patients ultimately still require imaging surveillance after successful resection. A prophylactic total pancreatectomy is rarely performed because the subsequent pancreatic endocrine (diabetes mellitus) and exocrine deficits (malnutrition) carry an increased morbidity.

BRANCH DUCT IPMNs

Localized branch-duct IPMN can be treated with a formal anatomic pancreatectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, or distal pancreatectomy, depending on the location of the lesion. However, guidelines were established that allow for nonoperative management with certain branch- type IPMN characteristics.

These include asymptomatic patients with a cyst size less than 3 cm and lack of mural nodules. The data to support this demonstrate a very low incidence of malignancy (approximately 2%) in this patient group. Which nearly matches the anticipated mortality of undergoing a formal anatomic resection. In approximately 20% to 30% of patients with branch- duct IPMNs, there is evidence of multifocality. The additional IPMNs can be visualized on high-resolution CT or MRI imaging. Ideally, patients with multifocal branch-duct IPMNs should undergo a total pancreatectomy. However, as previously mentioned, the increased morbidity and lifestyle alterations associated with a total pancreatectomy allows for a more conservative approach. This would include removing the most suspicious or dominant of the lesions in an anatomic resection and follow-up imaging surveillance of the remaining pancreas remnant. If subsequent imaging demonstrates malignant charac- teristics, a completion pancreatectomy is usually indicated.

RECURRENCE RATES

Recurrence rates with IPMNs are variable. An anatomic resection of a branch-duct IPMN with negative margins has been shown to be curative. The recurrence of a main- duct IPMN in the remnant gland is anywhere from 0% to 10% if the margins are negative and there is no evidence of invasion. Most case series cite a 5-year survival rate of at least 70% after resection of noninvasive IPMNs. In contrast, evidence of invasive disease, despite negative margins, decreases 5-year survival to 30% to 50%. The recurrence rate in either the pancreatic remnant or distant sites approaches 50% to 90% in these patients. Histopathologic subtype of the IPMN is correlated with survival. The aggressive tubular subtype has a 5-year survival ranging from 37% to 55% following surgical resection, whereas the colloid subtype has 5-year survival ranging from 61% to 87% post resection. Factors associated with decreased survival include tubular subtype, lymph node metastases, vascular invasion, and positive margins. IPMNs with evidence of invasion should be treated similar to pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Studies show that IPMNs tend to have better survival than pancreatic adenocarcinoma. This survival benefit may be secondary to the less aggressive tumor biology or the earlier diagnosis of IPMNs.

SURVEILLANCE

All patients who have a resected IPMN should undergo imaging surveillance. There is continual survival benefit with further resection if an IPMN does recur. International Consensus Guidelines published in 2017 offer recom- mendations for the frequency and modality of imaging surveillance after resection. Routine serum measurement of CEA and CA 19-9 has a limited role for detection of an IPMN recurrence. Of note, a new pancreatic lesion discovered on imaging after resection could represent a postoperative pseudocyst, a recurrence of the IPMN from inadequate resection, a new IPMN, or an unrelated new neoplastic process. IPMNs may also be associated with extrapancreatic neoplasms (stomach, colon, rectum, lung, breast) and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. It is unclear if this represents a true genetic syndrome. However, patients with IPMNs should have a discussion about the implications of their disease with their physician and are encouraged to undergo colonoscopy to exclude a synchronous neoplastic process.

The incidence of PANCREATIC CYSTIC LESIONS will continue to increase as imaging technology improves. EUS, cytology, and molecular panels have made differentiating the type of PCN less problematic. The importance of an accurate preoperative diagnosis ensures that operative management is selectively offered to those with high-risk lesions. Management beyond surgery, including adjuvant therapy and surveillance, continue to be active areas of research.

Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Resection Versus Transplantation

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the second most common cause of cancer mortality worldwide and its incidence is rising in North America, with an estimated 35,000 cases in the U.S. in 2014. The best chance for cure is surgical resection in the form of either segmental removal or whole organ transplantation although recent survival data on radiofrequency ablation approximates surgical resection and could be placed under the new moniker of “thermal resection”. The debate between surgical resection and transplantation focuses on patients with “within Milan criteria” tumors, single tumors, and well compensated cirrhosis who can safely undergo either procedure. Although transplantation historically has had better survival outcomes, early diagnosis, reversal of liver disease, and innovations in patient selection and neo-adjuvant therapies have led to similar 5-year survival. Transplantation clearly has less risk of tumor recurrence but exposes recipients to long term immunosuppression and its side effects. Liver transplantation is also limited by the severe global limit on the supply of organ donors whereas resection is readily available. The current data does not favor one treatment over the other for patients with minimal or no portal hypertension and normal synthetic function. Instead, the decision to resect or transplant for HCC relies on multiple factors including tumor characteristics, biology, geography, co-morbidities, location, organ availability, social support and practice preference.

Resection Versus Transplantation

The debate between resection and transplantation revolves around patients who have well compensated cirrhosis with Milan criteria resectable tumors. Patients within these criteria represent a very small proportion of those who initially present with HCC. This is especially true in western countries where hepatitis C is the most common cause of liver failure and HCC is a result of the progressive and in most cases advanced cirrhosis.

Given the need for a large number of patients to show statistical significance, it would be difficult to perform a high-quality prospective randomized controlled trial comparing resection and transplantation. In fact the literature revealed that no randomized controlled trials addressing this issue exist. Instead, outcomes of surgical treatment for HCC stem from retrospective analyses that have inherent detection, selection and attrition biases.

Given the numerous articles available on this subject, several meta-analyses have been published to delineate the role of transplantation and resection for treatment of HCC. However, there is reason to be wary of these meta-analyses because they pool data from heterogeneous populations with variable selection criteria and treatment protocols. One such meta-analysis by Dhir et al. focused their choice of articles to strict criteria which excluded studies with non-cirrhotic patients, fibrolamellar HCC and hepato-cholangiocarcinomas but included those with HCC within Milan criteria and computation of 5-year survival; between 1990 and 2011 they identified ten articles that fit within these criteria, of which six were ITT analyses, six included only well-compensated cirrhotics (Child-Pugh Class A without liver dysfunction) and three were ITT analyses of well-compensated cirrhotics.

Analysis of the six ITT studies that included all cirrhotics (n = 1118) (Child-Pugh Class A through C) showed no significant difference in survival at 5 years (OR = 0.600, 95 % CI 0.291– 1.237 l; p=0.166) but ITT analysis of only well-compensated cirrhotics (Child- Pugh Class A) revealed that patients undergoing transplant had a significantly higher 5-year survival as compared to those with resection (OR=0.521, 95 % CI 0.298–0.911; p=0.022).

A more recent ITT retrospective analysis from Spain assessed long-term survival and tumor recurrence following resection or transplant for tumors <5 cm in 217 cirrhotics (Child-Pugh Class A, B and C) over the span of 16 years. Recurrence at 5 years was significantly higher in the resection group (71.6 % vs. 16 % p<0.001) but survival at 4 years was similar (60 % vs. 62 %) which is likely explained by the evolving role of adjuvant therapies to treat post-resection recurrence.

Conclusions

- Patients with anatomically resectable single tumors and no cirrhosis or Child-Pugh Class A cirrhosis with normal bilirubin, HVPG (<10 mmHg), albumin and INR can be offered resection (evidence quality moderate; strong recommendation).

- Patients with Milan criteria tumors in the setting of Child- Pugh Class A with low platelets and either low albumin or high bilirubin or Child-Pugh Class B and C cirrhosis, especially those with more than one tumor, should be offered liver transplantation over resection (evidence quality moderate; strong recommendation).

- Those with Milan criteria tumors and Child-Pugh Class A cirrhosis without liver dysfunction should be considered for transplantation over resection (evidence quality low; weak recommendation).

- No recommendation can be made in regard to transplanting tumors beyond Milan criteria (evidence quality low) except to follow regional review board criteria.

- Pre-transplant therapies such as embolic or thermal ablation are safe and by expert opinion considered to be effective in decreasing transplant waitlist dropout and bridging patients to transplant (evidence quality low, weak recommendation). These interventions should be considered for those waiting longer than 6 months (evi- dence quality low, moderate recommendation).

- Living donor liver transplantation is a safe and effective option for treatment of HCC that are within and exceed Milan criteria (evidence quality moderate, weak recommendation).

The century of THE SURGEONS

Surgery is a profession defined by its authority to cure by means of bodily invasion. The brutality and risks of opening a living person’s body have long been apparent, the benefits only slowly and haltingly worked out. Nonetheless, over the past two centuries, surgery has become radically more effective, and its violence substantially reduced — changes that have proved central to the development of mankind’s abilities to heal the sick.

Consider, for instance, amputation of the leg.

The procedure had long been recognized as lifesaving, in particular for compound fractures and other wounds prone to sepsis, and at the same time horrific. Before the discovery of anesthesia, orderlies pinned the patient down while an assistant exerted pressure on the femoral artery or applied a tourniquet on the upper thigh.

Surgeons using the circular method proceeded through the limb in layers, taking a long curved knife in a circle through the skin first, then, a few inches higher up, through the muscle, and finally, with the assistant retracting the muscle to expose the bone a few inches higher still, taking an amputation saw smoothly through the bone so as not to leave splintered protrusions. Surgeons using the flap method, popularized by the British surgeon Robert Liston, stabbed through the skin and muscle close to the bone and cut swiftly through at an oblique angle on one side so as to leave a flap covering the stump.

The limits of patients’ tolerance for pain forced surgeons to choose slashing speed over precision. With either the flap method or the circular method, amputation could be accomplished in less than a minute, though the subsequent ligation of the severed blood vessels and suturing of the muscle and skin over the stump sometimes required 20 or 30 minutes when performed by less experienced surgeons.

No matter how swiftly the amputation was performed, however, the suffering that patients experienced was terrible. Few were able to put it into words. Among those who did was Professor George Wilson. In 1843, he underwent a Syme amputation — ankle disarticulation — performed by the great surgeon James Syme himself. Four years later, when opponents of anesthetic agents attempted to dismiss them as “needless luxuries,” Wilson felt obliged to pen a description of his experience:

“The horror of great darkness, and the sense of desertion by God and man, bordering close on despair, which swept through my mind and overwhelmed my heart, I can never forget, however gladly I would do so. During the operation, in spite of the pain it occasioned, my senses were preternaturally acute, as I have been told they generally are in patients in such circumstances. I still recall with unwelcome vividness the spreading out of the instruments: the twisting of the tourniquet: the first incision: the fingering of the sawed bone: the sponge pressed on the flap: the tying of the blood-vessels: the stitching of the skin: the bloody dismembered limb lying on the floor.”

It would take a little while for surgeons to discover that the use of anesthesia allowed them time to be meticulous. Despite the advantages of anesthesia, Liston, like many other surgeons, proceeded in his usual lightning-quick and bloody way. Spectators in the operating-theater gallery would still get out their pocket watches to time him. The butler’s operation, for instance, took an astonishing 25 seconds from incision to wound closure. (Liston operated so fast that he once accidentally amputated an assistant’s fingers along with a patient’s leg, according to Hollingham. The patient and the assistant both died of sepsis, and a spectator reportedly died of shock, resulting in the only known procedure with a 300% mortality.)

The Surgical Personality

Surgical stereotypes are remnants of the days of pre-anaesthesia surgery and include impulsivity, narcissism, authoritativeness, decisiveness, and thinking hierarchically. Medical students hold these stereotypes of surgeons early in their medical training. As Pearl Katz says in the The Scalpel’s Edge: ‘Each generation perpetuates the culture and passes it on by recruiting surgical residents who appear to resemble them and training these residents to emulate their thinking and behaviour.’ The culture of surgery has evolved, and certain behaviours are rightly no longer seen as acceptable, Non-technical skills such as leadership and communication have become incorporated into surgical training. Wen Shen, Associate Professor of Clinical Surgery at University of California San Francisco, argues that this has gone too far: ‘Putting likeability before surgical outcomes is like judging a restaurant by the waiters and ignoring the food,’ I would argue that operative and communication skills are indivisible, An aggressive surgeon is a threat to patient safety if colleagues are frightened to speak up for fear of a colleague shouting or, worse, throwing instruments. Conversely, a flattened hierarchy promotes patient safety.

Read More

Article: The Surgical Personality

The “GOOD” Surgeon

Surgery is an extremely enjoyable, intellectually demanding and satisfying career, and many more people apply to become surgeons each year than there are available places.

Those who are successful have to be ready not just to learn a great deal, but have the right kind of personality for the job.

Is a surgical career right for you?

Read the link…

THE GOOD SURGEON

Modern Concepts of Pancreatic Surgery

Operations on the gallbladder and bile ducts are among the surgical procedures most commonly performed by general surgeons. In most hospitals, cholecystectomy is the most frequently performed operation within the abdomen. Pancreatic surgery is less frequent , but because of the close relation between the biliary system and the pancreas, knowledge of pancreatic problems is equally essential to the surgeon. Acute and chronic pancreatitis and cancer of the pancreas are often encountered by surgeons, with apparently increasing frequency; their treatment remains difficult and perplexing. This review demonstrates the modern aspects of pancreatic surgery. Good study.

Operations on the gallbladder and bile ducts are among the surgical procedures most commonly performed by general surgeons. In most hospitals, cholecystectomy is the most frequently performed operation within the abdomen. Pancreatic surgery is less frequent , but because of the close relation between the biliary system and the pancreas, knowledge of pancreatic problems is equally essential to the surgeon. Acute and chronic pancreatitis and cancer of the pancreas are often encountered by surgeons, with apparently increasing frequency; their treatment remains difficult and perplexing. This review demonstrates the modern aspects of pancreatic surgery. Good study.

AULA: PRÍNCIPIOS MODERNOS DA CIRURGIA PANCREÁTICA

Palestras e Vídeoaulas

Vejam nos links a seguir algumas de nossas palestras disponíveis para download no Canal do SlideShare e Videoaulas presentes no You Tube.

Postoperative Delirium

Postoperative delirium is recognized as the most common surgical complication in older adults,occurring in 5% to 50% of older patients after an operation. With more than one-third of all inpatient operations in the United States being performed on patients 65 years or older, it is imperative that clinicians caring for surgical patients understand optimal delirium care. Delirium is a serious complication for older adults because an episode of delirium can initiate a cascade of deleterious clinical events, including other major postoperative complications, prolonged hospitalization, loss of functional independence, reduced cognitive function, and death. The annual cost of delirium in the United States is estimated to be $150 billion. Delirium is particularly compelling as a quality improvement target, because it is preventable in up to 40% of patients; therefore, it is an ideal candidate for preventive interventions targeted to improve the outcomes of older adults in the perioperative setting. Delirium diagnosis and treatment are essential components of optimal surgical care of older adults, yet the topic of delirium is under-represented in surgical teaching.

Postoperative Delirium in Older Adults

Surgical treatment of ACUTE PANCREATITIS

Acute pancreatitis is more of a range of diseases than it is a single pathologic entity. Its clinical manifestations range from mild, perhaps even subclinical, symptoms to a life-threatening or life-ending process. The classification of acute pancreatitis and its forms are discussed in fuller detail by Sarr and colleagues elsewhere in this issue. For the purposes of this discussion, the focus is on the operative interventions for acute pancreatitis and its attendant disorders. The most important thing to consider when contemplating operative management for acute pancreatitis is that we do not operate as much for the acute inflammatory process as for the complications that may arise from inflammation of the pancreas. In brieSurgical treatment of acute pancreatitisf, the complications are related to: necrosis of the parenchyma, infection of the pancreas or surrounding tissue, failure of pancreatic juice to safely find its way to the lumen of the alimentary tract, erosion into vascular or other structures, and a persistent systemic inflammatory state. The operations may be divided into three major categories: those designed to ameliorate the emergent problems associated with the ongoing inflammatory state, those designed to ameliorate chronic sequelae of an inflammatory event, and those designed to prevent a subsequent episode of acute pancreatitis. This article provides a review of the above.

SURGICAL TREATMENT OF ACUTE PANCREATITIS

O TEMPLO DO CIRURGIÃO.

Templo (do latim templum, “local sagrado”) é uma estrutura arquitetônica dedicada ao serviço religioso. O termo também pode ser usado em sentido figurado. Neste sentido, é o reflexo do mundo divino, a habitação de Deus sobre a terra, o lugar da Presença Real. É o resumo do macrocosmo e também a imagem do microcosmo: ‘o corpo é o templo do Espírito Santo’ (I, Coríntios, 6, 19).

Dos locais especiais, O corpo humano (morada da alma), a Cavidade Peritoneal e o Bloco Cirúrgico, se bem analisados, são muito semelhantes e merecem atitudes e comportamentos respeitáveis. O Templo, em todos os credos, induz à meditação, absoluto silêncio tentando ouvir o Ser Supremo. A cavidade peritoneal | abdominal , espaço imaculado da homeostase, quando injuriada, reage gritando em dor, implorando uma precoce e efetiva ação terapêutica.

O Bloco Cirúrgico, abrigo momentâneo do indivíduo solitário, que mudo e quase morto de medo, recorre à prece implorando a troca do acidente, da complicação, da recorrência, da seqüela, da mutilação, da iatrogenia e do risco de óbito pela agressiva e controlada intervenção que lhe restaure a saúde, patrimônio magno de todo ser vivo.

O Bloco Cirúrgico clama por respeito ao paciente cirúrgico, antes mesmo de ser tomado por local banal, misturando condutas vulgares, atitudes menores, desvio de comportamento e propósitos secundários. Trabalhar no Bloco Cirúrgico significa buscar a perfeição técnica, revivendo os ensinamentos de William Stewart Halsted , precursor da arte de operar, dissecando para facilitar, pinçando e ligando um vaso sangüíneo, removendo tecido macerado, evitando corpos estranhos e reduzindo espaço vazio, numa síntese feita com a ansiedade e vontade da primeira e a necessidade e experiência da última.

Mas, se a cirurgia e o cirurgião vêm sofrendo grande evolução, técnica a primeira e científica o segundo, desde o início do século, a imagem que todo doente faz persiste numa simbiose entre mitos e verdades. A cirurgia significa enfrentar ambiente desconhecido chamado “sala de cirurgia” onde a fobia ganha espaço rumo ao infinito. O medo ainda prepondera em muitos.

A confiança neste momento além de um reconhecimento é um troféu que o cirurgião recebe dos pacientes e seus familiares. Tanto a CONFIANÇA quanto a SEGURANÇA têm que ser preservadas a qualquer custo. Não podem correr o risco de serem corroídas por palavras e atitudes de qualquer membro da equipe cirúrgica. Não foi tarefa fácil transformar, para a população, o ato cirúrgico numa atividade científica, indispensável, útil e por demais segura. Da conquista da cirurgia, como excelente arma terapêutica para a manutenção de um alto padrão de qualidade técnica, resta a responsabilidade dos cirurgiões, os herdeiros do suor e sangue, que se iniciou com o trabalho desenvolvido por Billroth, Lister, Halsted, Moyniham, Kocher e uma legião de figuras humanas dignas do maior respeito, admiração e gratidão universal.

No ato operatório os pacientes SÃO TODOS SEMELHANTES EM SUAS DIFERENÇAS, desde a afecção, ao prognóstico, ao caráter da cirurgia e especialmente sua relação com o ato operatório. Logo, o cirurgião tem por dever de ofício entrar no bloco cirúrgico com esperança e não deve sair com dúvida. Nosso trabalho é de equipe, cada um contribui com uma parcela, maior ou menor, para a concretização do todo, do ato cirúrgico por completo, com muita dedicação, profissionalismo e sabedoria. Toda tarefa, da limpeza do chão ao ato de operar, num crescendo, se faz em função de cada um e em benefício da maioria, o mais perfeito possível e de uma só vez, quase sempre sem oportunidade de repetição e previsão de término.

O trabalho do CIRURGIÃO é feito com carinho, muita dignidade, humildade e executado em função da alegria do resultado obtido aliado a dimensão ética do dever cumprido que transcende a sua existência. A vida do cirurgião se materializa no ato operatório e o bloco cirúrgico, palco do nosso trabalho não tolera e jamais permite atitudes menores, inferiores, ambas prejudiciais a todos os pacientes e a cada cirurgião. Como ambiente de trabalho de uma equipe diversificada, precisamos manter, a todo custo, o controle de qualidade, eficiência, eficácia e efetividade técnina associados aos mais altos valores ético, pois lidamos com o que há de mais precioso da criação divina na Terra: O SER HUMANO.

“Tem presença de Deus, como já a tens. Ontem estive com um doente, um doente a quem quero com todo o meu coração de Pai, e compreendo o grande trabalho sacerdotal que os médicos levam a cabo. Mas não se ponham orgulhosos, porque todas as almas são sacerdotais. Devem pôr em prática esse sacerdócio! Ao lavares as mãos, ao vestires a bata, ao calçares as luvas, pensa em Deus, e pensa nesse sacerdócio real de que fala São Pedro, e então não se te meterá a rotina: farás bem aos corpos e às almas” São Josemaria Escriva

Bariatric Complications

Over the past decade, following the publication of several long-term outcome studies that showed a significant improvement in cardiovascular risk and mortality after bariatric surgery, the number of bariatric procedures being carried out annually in the UK has grown exponentially. Surgery remains the only way to produce significant, sustainable weight loss and resolution of comorbidities. Nevertheless, relatively few surgeons have developed an interest in this field. Most bariatric surgery is now performed in centres staffed by surgeons with a bariatric interest, usually as part of a multidisciplinary team.

The commonest weight loss procedures performed around the world at present are the gastric band, the gastric bypass and the sleeve gastrectomy. In very obese patients, an alternative operation is the duodenal switch, while the new ileal transposition procedure represents one of the few purely metabolic operations designed specifically for the treatment of type II diabetes. Older operations such as vertical banded gastroplasty and jejuno-ileal bypass are now obsolete, although patients who have undergone such procedures in the distant past may still present to hospital with complications. The main endoscopic option at present is insertion of a gastric balloon, with newer procedures like the endoscopic duodenojejunal barrier and gastric plication on the horizon. Implantable neuroregulatory devices (gastric ‘pacemakers’) represent a new direction for surgical weight control by harnessing neural feedback signals to help control eating.

It should be within the capability of any abdominal surgeon to manage the general complications of bariatric surgery, which include pulmonary atelectasis/pneumonia, intra-abdominal bleeding, anastomotic or staple-line leak with or without abscess formation, deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/pulmonary embolus and superficial wound infections. Patients may be expected to present with malaise, pallor, features of sepsis or obvious wound problems. However, clinical features may be difficult to recognise owing to body habitus. Abdominal distension, tenderness and guarding may be impossible to determine clinically due to the patient’s obesity. Pallor is non-specific. Fever and leucocytosis may be absent. Wound collections may be very deep. These complications in a bariatric patient should be actively sought with appropriate investigations. In particular, it is vital for life-threatening complications such as bleeding, sepsis and bowel obstruction to be recognised promptly and treated appropriately. A persistent tachycardia may be the only sign heralding significant complications and should always be taken seriously. It is useful to classify complications as ‘early’, ‘medium’ and ‘late’ because, from the receiving clinician’s point of view, the differential diagnosis will differ accordingly.

Complications of bariatric surgery presenting to the GENERAL SURGEON

A “PROFISSÃO” CIRÚRGICA

“A arte de curar vem do coração e da mente mais do que das mãos.” – Hipócrates

“A arte de curar vem do coração e da mente mais do que das mãos.” – Hipócrates

Na complexa tapeçaria da sociedade moderna, as profissões desempenham papéis fundamentais na organização dos serviços necessários ao bem-estar coletivo. Definida pelo American College of Surgeons, uma profissão é um campo onde a maestria de um corpo complexo de conhecimento e habilidades é essencial. É uma vocação em que o conhecimento científico ou a prática de uma arte, fundamentada nesse conhecimento, é empregada em benefício dos outros. O compromisso com a competência, a integridade e a moralidade forma a base de um contrato social entre a profissão e a sociedade, que concede à profissão um monopólio sobre o uso de seu conhecimento, considerável autonomia na prática e o privilégio da auto-regulação. Em troca, a profissão deve prestar contas a quem serve e à sociedade como um todo.

Os Elementos Essenciais da Profissão

No cerne de toda profissão estão quatro elementos fundamentais:

- Monopólio do Conhecimento Especializado: Profissionais detêm o direito exclusivo de utilizar conhecimentos e habilidades especializados, o que lhes confere uma posição única na sociedade.

- Autonomia e Auto-Regulação: Em troca deste monopólio, profissionais desfrutam de uma relativa autonomia na prática e são responsáveis pela sua própria regulação.

- Serviço Altruísta: A profissão deve servir tanto indivíduos quanto a sociedade de forma altruísta, colocando o bem-estar do paciente acima de outros interesses.

- Responsabilidade pela Manutenção e Expansão do Conhecimento: Profissionais são responsáveis por atualizar e expandir continuamente seu conhecimento e habilidades.

O Que é Profissionalismo?

Profissionalismo descreve as qualidades cognitivas, morais e colegiais de um profissional. É o conjunto de razões pelas quais um pai se orgulha de dizer que seu filho é um médico e cirurgião. Profissionalismo é mais do que apenas conhecimento técnico; é uma combinação de ética, respeito e dedicação ao ofício e ao paciente.

Por Que Precisamos de um Código de Conduta Profissional?

A confiança é o alicerce da prática cirúrgica. O Código de Conduta Profissional esclarece a relação entre a profissão cirúrgica e a sociedade que serve, frequentemente referido como contrato social. Para os pacientes, o código cristaliza o compromisso da comunidade cirúrgica em relação aos indivíduos e suas comunidades. A confiança é construída, tijolo por tijolo.

O Código de Conduta Profissional

O Código de Conduta Profissional aplica os princípios gerais do profissionalismo à prática cirúrgica e serve como a fundação sobre a qual os privilégios profissionais e a confiança dos pacientes e do público são conquistados. Durante o cuidado pré-operatório, intraoperatório e pós-operatório, os cirurgiões têm a responsabilidade de:

- Advogar Eficazmente pelos interesses dos pacientes.

- Divulgar Opções Terapêuticas incluindo seus riscos e benefícios.

- Divulgar e Resolver Conflitos de Interesse que possam influenciar as decisões de cuidado.

- Ser Sensível e Respeitoso com os pacientes, compreendendo sua vulnerabilidade durante o período perioperatório.

- Divulgar Completamente Eventos Adversos e Erros Médicos.

- Reconhecer Necessidades Psicológicas, Sociais, Culturais e Espirituais dos pacientes.

- Incorporar Cuidados Especiais para Pacientes Terminais.

- Reconhecer e Apoiar as Necessidades das Famílias dos Pacientes.

- Respeitar o Conhecimento, Dignidade e Perspectiva de outros profissionais de saúde.

A Necessidade do Código de Profissionalismo para Cirurgiões

Procedimentos cirúrgicos são experiências extremas que impactam os pacientes fisiológica, psicológica e socialmente. Quando os pacientes se submetem a uma experiência cirúrgica, devem confiar que o cirurgião colocará seu bem-estar acima de todas as outras considerações. O código escrito ajuda a reforçar esses valores, garantindo que a confiança e o compromisso sejam mantidos.

Princípios Fundamentais do Código de Conduta Profissional

- Primazia do Bem-Estar do Paciente: Os interesses do paciente sempre devem vir em primeiro lugar. O altruísmo é central para esse conceito, e é o altruísmo do cirurgião que fomenta a confiança na relação médico-paciente.

- Autonomia do Paciente: Pacientes devem entender e tomar suas próprias decisões informadas sobre o tratamento. Os médicos devem ser honestos para que os pacientes façam escolhas educadas, garantindo que essas decisões estejam alinhadas com práticas éticas.

- Justiça Social: Como médicos, devemos advogar pelos pacientes individuais enquanto promovemos a saúde do sistema de saúde como um todo. Precisamos equilibrar as necessidades dos pacientes (autonomia) sem desviar recursos escassos que beneficiariam a sociedade (justiça social).

“Não há maior coisa a ser conquistada do que a confiança dos pacientes e da sociedade, pois ela é a base sobre a qual construímos nossas práticas e nossa profissão.” – William Osler

Tratamento Cirúrgico da Hemorragia digestiva alta por varizes esofágicas | Hipertensão Porta

O sistema portal é uma rede venosa de baixa pressão, com níveis fisiológicos <5 mmHg. Desta forma, o termo hipertensão portal (HP) designa uma síndrome clínica caracterizada pelo aumento mantido na pressão venosa em níveis acima dos fisiológicos. Ela é considerada clinicamente significante quando acima de 10 mmHg; neste nível existe o risco de surgimento de varizes esofagogástricas (VEG). Por sua vez, valores acima de 12 mmHg cursam com risco de rompimento dessas varizes, sua principal complicação.

ARTIGO DE REVISÃO – HIPERTENSÃO PORTAL

O aumento do fluxo como fator preponderante inicial da HP é raro e representado por fístulas arterioportais congênitas, traumáticas ou neoplásicas. O aumento da resistência é a condição fisiopatológica inicial mais comum e pode ser classificada de acordo com o local de obstrução ao fluxo em: pré-hepática, intra-hepática e pós-hepática. A HP intra-hepática responde pela grande maioria dos casos e pode ser subdividida de acordo com o local de acometimento estrutural no parênquima hepático em: pré-sinusoidal (ex: esquistossomose hepatoesplênica – EHE), sinusoidal (ex: cirrose hepática) e pós-sinusoidal (ex: doença venoclusiva). Em nosso meio, a maioria dos casos é decorrente da EHE e das hepatopatias crônicas complicadas com cirrose.

O tratamento da HP depende da causa subjacente, da condição clínica e do momento em que é realizado. Pacientes com função hepática comprometida têm abordagem diversa daqueles com ela preservada, como os portadores de EHE. Além disso, o tratamento pode ser emergencial (durante episódio agudo de hemorragia) ou eletivo, como profilaxia pré-primária, primária ou secundária. Por essa diversidade de situações clínicas, não existe modalidade única de tratamento.

O objetivo da aula abaixo foi avaliar os avanços e as estratégias atuais empregadas no tratamento emergencial e eletivo da hemorragia digestiva varicosa em pacientes cirróticos e esquistossomóticos.

AULA: TRATAMENTO CIRÚRGICO DA HIPERTENSÃO PORTAL

FERIDA PÓS-OPERATÓRIA

A avaliação e os cuidados de feridas pós-operatórias deve ser do domínio de todos os profissionais que atuam na clínica cirúrgica. O conhecimento a cerca dos processos relacionados a cicatrização tecidual é importante tanto nos cuidados como na prevenção de complicações, tais como: infecções e deiscência. Como tal, todos os profissionais médicos, sendo eles cirurgiões ou de outras especialidades, que participam do manejo clínico dos pacientes no período perioperatório devem apreciar a fisiologia da cicatrização de feridas e os princípios de tratamento de feridas pós-operatório. O objetivo deste artigo é atualizar os profissionais médicos de outras especialidades sobre os aspectos importantes do tratamento de feridas pós-operatório através de uma revisão da fisiologia da cicatrização de feridas, os métodos de limpeza e curativo, bem como um guia sobre complicações de feridas pós-operatórias mais prevalentes e como devem ser manejados nesta situação.

Esophagectomy: Anastomotic Complications (Leakage and Stricture)

Esophagectomy can be used to treat several esophageal diseases; it is most commonly used for treatment of esophageal cancer. Esophagectomy is a major procedure that may result in various complications. This article reviews only the important complications resulting from esophageal resection, which are anastomotic complications after esophageal reconstruction (leakage and stricture), delayed emptying or dumping syndrome, reflux, and chylothorax.

Causas de conversão da VIDEOCOLECISTECTOMIA

Atualmente, a colecistectomia laparoscópica é a abordagem preferida para o tratamento da litíase biliar, representando cerca de 90% dos procedimentos realizados, uma marca alcançada nos Estados Unidos em 1992. A popularidade dessa técnica se deve a suas vantagens evidentes: menos dor no pós-operatório, recuperação mais rápida, redução dos dias de trabalho perdidos e menor tempo de hospitalização. Apesar de ser considerada o padrão-ouro na cirurgia biliar, a colecistectomia laparoscópica não está isenta de desafios. Entre 2% e 15% dos casos podem exigir a conversão para cirurgia convencional. Os motivos mais comuns para essa conversão incluem dificuldades na identificação da anatomia, suspeita de lesão da árvore biliar e controle de sangramentos. Identificar os fatores que contribuem para uma maior taxa de conversão é essencial para a equipe cirúrgica. Isso não apenas permite uma avaliação mais precisa da complexidade do procedimento, mas também ajuda na preparação do paciente para possíveis riscos e na mobilização de cirurgiões mais experientes quando necessário. Em um cenário onde a precisão e a segurança são cruciais, a compreensão dos desafios e a preparação adequada podem fazer toda a diferença no resultado da cirurgia.

Relacionados ao Paciente: 1. Obesidade (IMC > 35), 2. Sexo Masculino, 3. Idade > 65 anos, 4. Diabetes Mellitus e 5. ASA > 2.

Relacionadas a Doença: 1. Colecistite Aguda, 2. Líquido Pericolecístico, 3. Pós – CPRE, 4. Síndrome de Mirizzi e 5. Edema da parede da vesícula > 5 mm.

Relacionadas a Cirurgia: 1. Hemorragia, 2. Aderências firmes, 3. Anatomia obscura, 4. Fístulas internas e 5. Cirurgia abdominal prévia.

POST-HEPATECTOMY ADVERSE EVENTS

Hepatic resection had an impressive growth over time. It has been widely performed for the treatment of various liver diseases, such as malignant tumors, benign tumors, calculi in the intrahepatic ducts, hydatid disease, and abscesses. Management of hepatic resection is challenging. Despite technical advances and high experience of liver resection of specialized centers, it is still burdened by relatively high rates of postoperative morbidity and mortality. Especially, complex resections are being increasingly performed in high risk and older patient population. Operation on the liver is especially challenging because of its unique anatomic architecture and because of its vital functions. Common post-hepatectomy complications include venous catheter-related infection, pleural effusion, incisional infection, pulmonary atelectasis or infection, ascites, subphrenic infection, urinary tract infection, intraperitoneal hemorrhage, gastrointestinal tract bleeding, biliary tract hemorrhage, coagulation disorders, bile leakage, and liver failure. These problems are closely related to surgical manipulations, anesthesia, preoperative evaluation and preparation, and postoperative observation and management. The safety profile of hepatectomy probably can be improved if the surgeons and medical staff involved have comprehensive knowledge of the expected complications and expertise in their management.

Classroom: Hepatic Resections

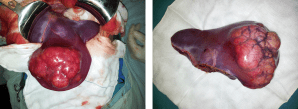

The era of hepatic surgery began with a left lateral hepatic lobectomy performed successfully by Langenbuch in Germany in 1887. Since then, hepatectomy has been widely performed for the treatment of various liver diseases, such as malignant tumors, benign tumors, calculi in the intrahepatic ducts, hydatid disease, and abscesses. Operation on the liver is especially challenging because of its unique anatomic architecture and because of its vital functions. Despite technical advances and high experience of liver resection of specialized centers, it is still burdened by relatively high rates of postoperative morbidity (4.09%-47.7%) and mortality (0.24%-9.7%). This review article focuses on the major postoperative issues after hepatic resection and presents the current management.

REVIEW_ARTICLE_HEPATECTOMY_COMPLICATIONS

PANCREATIC PSEUDOCYST

Classroom: Principles of Pancreatic Surgery

The pancreatic pseudocyst is a collection of pancreatic secretions contained within a fibrous sac comprised of chronic inflammatory cells and fibroblasts in and adjacent to the pancreas contained by surrounding structures. Why a fibrous sac filled with pancreatic fluid is the source of so much interest, speculation, and emotion amongst surgeons and gastroenterologists is indeed hard to understand. Do we debate so vigorously about bilomas, urinomas, or other abdominal collections of visceral secretions? Perhaps it is because the pancreatic pseudocyst represents a sleeping tiger, which though frequently harmless, still can rise up unexpectedly and attack with its enzymatic claws into adjacent visceral and vascular structures and cause lifethreatening complications. Another part of the debate and puzzlement about pancreatic pseudocysts is related to confusion about pancreatic pseudocyst definition and nomenclature. The Atlanta classification, developed in 1992, was a pioneering effort in describing and defining morphologic entities in acute pancreatitis. Since then, a working group has been revising this system to incorporate more modern experience into the terminology. In the latest version of this system, pancreatitis is divided into acute interstitial edematous pancreatitis (IEP) and necrotizing pancreatitis (NP), based on the presence of pancreatic tissue necrosis. The fluid collections associated with these two “types” of pancreatitis are also differentiated. Early (<4 weeks into the disease course) peripancreatic fluid collections in IEP are referred to as acute peripancreatic fluid collections (APFC), whereas in NP, they are referred to as postnecrotic peripancreatic fluid collections (PNPFC). Late (>4 weeks) fluid collections in IEP are called pancreatic pseudocysts, and in NP, they are called walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN).

10 Princípios da RELAÇÃO CIRURGIÃO-PACIENTE

Quando a perspectiva de uma cirurgia surge, seja para corrigir uma condição médica, melhorar a estética ou simplesmente enfrentar uma situação inesperada, o medo e a apreensão são reações naturais. A visão de dor, complicações e a sensação de perda de controle podem ser opressoras, especialmente diante dos avanços tecnológicos prometidos pela medicina. No entanto, para enfrentar esses desafios de forma eficaz e justa, é crucial entender o processo cirúrgico e os papéis envolvidos. Aqui estão algumas orientações para pacientes e familiares, com base em princípios éticos e práticos da medicina moderna.

1. Relação Paciente-Cirurgião (ã): Construindo Confiança

A confiança mútua entre paciente e médico é fundamental. Evite se submeter a pressões para procedimentos rápidos e impessoais. Um relacionamento humanizado, onde o médico dedica tempo para entender o paciente, é essencial para evitar acusações injustas e frustrações. As consultas devem ser um espaço para esclarecimentos detalhados e empáticos, não apenas para realizar procedimentos.

2. Clareza e Transparência na Informação

Informações claras sobre o procedimento, suas consequências e riscos são essenciais. Evite jargões técnicos e explique cada aspecto da cirurgia em termos compreensíveis. A comunicação aberta reduz a ansiedade e prepara os pacientes para os possíveis desdobramentos da cirurgia.

3. Expectativas Realistas

Especialmente em procedimentos estéticos, alinhar as expectativas do paciente com a realidade é crucial. Muitas vezes, expectativas irreais podem levar a descontentamentos. É importante discutir de maneira honesta o que a cirurgia pode realmente alcançar e o que pode ser meramente aspiracional.

4. Avaliação Abrangente do Risco

O risco cirúrgico não se limita a aspectos cardíacos. Uma avaliação completa deve considerar todos os sistemas do corpo e a saúde mental do paciente. Exames físicos completos e, se necessário, avaliações psicológicas são partes vitais do pré-operatório.

5. O Papel do Anestesiologista

A escolha e a administração da anestesia são responsabilidades cruciais e devem ser discutidas com o anestesiologista. A decisão sobre o tipo de anestesia deve considerar as melhores práticas e o estado de saúde do paciente, não apenas a preferência do cirurgião.

6. Preparação para Possíveis Mudanças

A cirurgia pode trazer surpresas. É importante que o paciente esteja ciente de que o plano cirúrgico pode mudar com base nas condições encontradas durante o procedimento. Essas mudanças podem influenciar o tempo de recuperação e os custos envolvidos.

7. Documentação Completa

Preencher adequadamente o prontuário médico é crucial. Todos os detalhes, desde os exames realizados até os esclarecimentos fornecidos, devem estar documentados com precisão. Essa prática não apenas protege o paciente, mas também o profissional médico.

8. Comunicação Detalhada do Procedimento

Descreva minuciosamente o ato cirúrgico e os materiais encaminhados para análise. Certifique-se de que todos os procedimentos sejam seguidos corretamente e que todos os materiais estejam devidamente identificados.

9. Pós-Operatório: Acompanhamento e Cuidados

O acompanhamento pós-operatório deve ser meticuloso. Registre as datas e horários das visitas médicas e todas as providências tomadas. Forneça orientações claras sobre a alta e o acompanhamento ambulatorial.

10. Atenção ao Estado Emocional do Paciente

Pacientes com instabilidade emocional podem ter uma experiência mais difícil com a cirurgia. É vital que essas questões sejam abordadas com apoio especializado para garantir que o paciente esteja mentalmente preparado para o procedimento.

Conclusão

A ética na medicina, especialmente na cirurgia, vai além dos conceitos de eficiência técnica e competência. Trata-se de respeito mútuo e comunicação aberta entre médico e paciente. A prática médica ideal exige não apenas habilidades técnicas e conhecimento, mas também empatia, compreensão e um compromisso com a integridade e o bem-estar do paciente. Assim, com preparação cuidadosa e uma abordagem centrada no paciente, é possível enfrentar os desafios da cirurgia com confiança e esperança. Esta abordagem humanizada e informativa ajuda a construir uma relação de confiança, minimizando o medo e a ansiedade associados ao tratamento cirúrgico e garantindo que todos os aspectos do cuidado sejam geridos com a maior consideração e respeito.

The General Surgery Job Market

There is a current shortage of general surgeons nationwide. A growing elderly population and ongoing trends toward increased health care use have contributed to a higher demand for surgical services, without a corresponding increase in the supply of surgeons. The number of general surgeons per 100,000 people in the United States declined by 26% from the 1980s to 2005. Cumulative growth in demand for general surgery is projected to exceed 25% by 2025. The Association of American Medical Colleges has projected a shortage of 41,000 general surgeons by 2025. General surgeons make up 33% of the total projected physician shortage, the second highest after primary care physicians, who make up 37% of the total shortage. Despite the demand for general surgeons, the percentage of general surgery trainees going directly into practice is decreasing while the percentage of trainees pursuing subspecialty training is increasing. A recent study reported that graduating residents who lacked confidence in their skills to operate independently were more likely to pursue subspecialty training. This suggests that some graduating residents are motivated to obtain subspecialty training to gain more experience rather than narrow their clinical scope of practice. Given the projected shortage of general surgeons, this will be a crucial distinction when reforming surgical education. General surgery trainees interested in career planning would benefit from understanding the demand for general and/or specialty skills in a job market heavily influenced by a constant stream of new graduates. However, little is currently known about the demand for subspecialty vs general surgical skills in the current job market. The goal of this study was to describe the current job market for general surgeons in the United States, using Oregon and Wisconsin as surrogates. Furthermore, we sought to compare the skills required by the job market with those of graduating trainees with the goal of gaining insight that might assist in workforce planning and surgical education reform.

PRINCIPLES OF OSTOMY MANAGEMENT

The creation of a stoma is a technical exercise. Like most undertakings, if done correctly, the stoma will usually function well with minimal complications for the remainder of the ostomate’s life. Conversely, if created poorly, stoma complications are common and can lead to years of misery. Intestinal stomas are in fact enterocutaneous anastomoses and all the principles that apply to creation of any anastomosis (i.e., using healthy intestine, avoiding ischemia and undue tension) are important in stoma creation.

MOST COMMOM POSTOPERATIVE PROBLEMS

Despite good preoperative assessment, surgical and anaesthetic technique and perioperative management, unexpected symptoms or signs arise after operation that may herald a complication. Detecting these early by regular monitoring and surgical review means early treatment can often forestall major deterioration. Managing problems such as pain, fever or collapse requires correct diagnosis then early treatment. Determining the cause can be challenging, particularly if the patient is anxious, in pain or not fully recovered from anaesthesia. It is vital to see and assess the patient and if necessary, arrange investigations, whatever the hour, when deterio-ration suggests potentially serious but often remediable complications. Consider also whether and when to call for senior help.

Survival Guide for SURGERY ROUND

SURGERY ROUND

Medical students are often attached to the various services. They can provide a significant contribution to patient care. However, their work requires supervision by the surgical intern/resident who takes primary clinical responsibility. Subinterns are senior medical students who are seeking additional clinical experience. Their assistance is needed and appreciated, but again, close supervision of their clinical responsibilities by the intern/resident is mandatory.Outside reading is recommended, including textbooks, reference sources, and monthly journals.Eating is prohibited in patient care areas.Maintain patient confidentiality at all times.At conferences use only patient initials in presentations; and speak carefully and respectfully on work rounds.

PRINCIPLES

1. Always be punctual (this includes ward rounds, operating room, clinics, conferences, morbidity and mortality). Personal appearance is very important. Maintain a high standard including clean shirt and tie (or equivalent) and a clean white coat. The day begins early. Be ready with all the data to start rounds with the senior resident or chief resident. Be sure to provide enough time each morning to examine your patients before rounds.

ABOUT NOTES

2.Aim to get all of your chart notes written as soon as possible; this will greatly increase your effi ciency during the day. Sign and print your name, and include your beeper number, date, and time. Progress notes on patients are required daily. Surgical progress notes should be succinct and accurate, briefl y summarizing the patient’s clinical status and plan of management. Someone unfamiliar with the case should be able to get a good understanding of the patient’s condition from one or two notes. Operative consent is obtained after admitting the patient, performing the history and physical examination, discussing the risks, benefi ts, and alternatives of the procedure(s), and having the patient’s nurse sign the consent with the patient. If you are unaware of the risks and benefi ts of a procedure, discuss this with the service chief resident. Blood transfusion attestation forms need to be signed by the counseling physician before each surgical procedure.

OPERATING ROOM

3. Arrive in the operating room with the patient and before the attending physician or chief resident. Make sure that the charts and all of the relevant x-rays are in the operating room. Make sure that the x-rays are on the x-ray view box prior to the commencement of the case. The intern or resident performing the case should be familiar with the patient’s history and physical exam, current medications, and comorbidities, and be familiar with the principles of the operation prior to arriving in the operating room. Make it a habit to introduce yourself to the patient before the operation. It is mandatory that the surgical resident involved with a case in the operating room attend the start of the case punctually. Scheduled operative cases do not necessarily occur at the listed time. For this reason, it is necessary to check with the operating room front desk frequently. Do not rely on being paged. Conduct in the operating room includes assisting with the preoperative positioning and preparation of the patient; this includes shaving, catheterization, protection of pressure points, and thromboembolism protection. The resident should escort the patient from the operating room to the intensive care unit (ICU) or the postanesthetic care unit with the anesthesiologists. The operating surgeon is responsible for dictating the case. The resident must record all cases performed. For cases admitted to the surgery ICU, a hand-over to the surgery ICU resident is mandatory.This includes discussing all the preoperative assessment, operative details, and postoperative management of the case with the ICU resident.

ROUNDS

4. Signing out to cross-cover services must be performed in a meticulous and careful fashion. All patients should be discussed between the surgical intern and the cross-covering intern to cover all potential problems. A sign-out list containing all the patients, patient locations, and the responsible attendings should be given personally to the cross-cover intern. Any investigations performed at night (e.g., lab studies, chest x-ray, electrocardiogram [ECG]) should be checked that night by the covering intern. No test order should go unchecked. Abnormal lab values should be reviewed and discussed with the senior resident or the attending staff, especially on preoperative patients. Starting antibiotics should be a decision left to the senior resident or attending staff. If consultants are asked to see patients, their recommendations mustbe discussed with your senior resident or attending priorto initiating any new plans. Independent thought is good; independent action is bad.

SUPERVISION

5. Document all procedures performed on patients—including arterial lines, chest tubes, and central lines—with a short procedure note in the chart. Every patient contact should be documented in the patient record.If you see a patient in the middle of the night, write a short note to describe your assessment and plan. Remember, if there is no documentation, then nobody responded to the patient’s complaint or needs. Obtain appropriate supervision for procedures. There are always more senior residents available if your chief is not. Protect yourself; practice universal precautions! Wash your hands before and after examining a patient. Wear gloves. All wounds should be inspected every day by the surgical intern as part of the clinical examination. Please re-dress them; the nursing staff is not always immediately available to do so. There should never be any surprises in the morning.

RESIDENTS

Your senior resident is responsible for the service and should be kept aware of any problems, regardless of the time of day. If the senior resident is not available, the attending staff should be contacted directly. There are always senior residents in the hospital who are available to be used as resources for emergencies. Always be aware of who is in-house (i.e., consult resident, ICU resident, trauma chief). A surgery resident’s days are long. They start early and they fi nish late. Always remember the three A’s to being a successful resident: Affable, Available, and Able. Be prepared to maintain a flexible daily schedule depending on the workload of the service and the requirement for additional manpower.

“COMO PODEMOS CURAR A MEDICINA?”

“Nos últimos anos percebemos que estávamos na mais profunda crise da existência da medicina, devido a algo sobre o que você normalmente não pensa quando você é um médico preocupado em fazer o bem para as pessoas, que é o custo do tratamento de saúde. Não há um país no mundo que não esteja perguntando agora se podemos custear o que médicos fazem. A luta política que desenvolvemos tornou-se aquela sobre se o governo é o problema ou se as companhias de seguro são o problema. E a resposta é sim e não; é mais profundo que tudo isso. A causa de nossos problemas é, na verdade, a complexidade que a ciência nos deu. E para entender isso, voltarei algumas gerações…”

“CIRURGIA: PASSADO, PRESENTE e FUTURO ROBÓTICO”

A cirurgiã e inventora Catherine Mohr nos guia pela história da cirurgia (e seu passado pré-anestesia e pré-antissepsia), e depois demonstra algumas das mais novas ferramentas para cirurgias realizadas através de pequenas incisões, usando ágeis mãos robóticas.

Ebook: Princípios da Cirurgia Hepatobiliar

Cirurgia Hepatobiliar