Principles of Surgical Resection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

There has been significant improvement in the perioperative results following liver resection, mainly due to techniques that help reduce blood loss during the operation. Extent of liver resection required in HCC for optimal oncologic results is still controversial. On this basis, the rationale for anatomically removing the entire segment or lobe bearing the tumor, would be to remove undetectable tumor metastases along with the primary tumor.

SIZE OF TUMOR VERSUS TUMOR FREE-MARGIN

Several retrospective studies and meta-analyses have shown that anatomical resections are safe in patients with HCC and liver dysfunction, and may offer a survival benefit. It should be noted, that most studies are biased, as non-anatomical resections are more commonly performed in patients with more advanced liver disease, which affects both recurrence and survival. It therefore remains unclear whether anatomical resections have a true long-term survival benefit in patients with HCC. Some authors have suggested that anatomical resections may provide a survival benefit in tumors between 2 and 5 cm. The rational is that smaller tumors rarely involve portal structures, and in larger tumors presence of macrovascular invasion and satellite nodules would offset the effect of aggressive surgical approach. Another important predictor of local recurrence is margin status. Generally, a tumor-free margin of 1 cm is considered necessary for optimal oncologic results. A prospective randomized trial on 169 patients with solitary HCC demonstrated that a resection margin aiming at 2 cm, safely decreased recurrence rate and improved long-term survival, when compared to a resection margin aiming at 1 cm. Therefore, wide resection margins of 2 cm is recommended, provided patient safety is not compromised.

THECNICAL ASPECTS

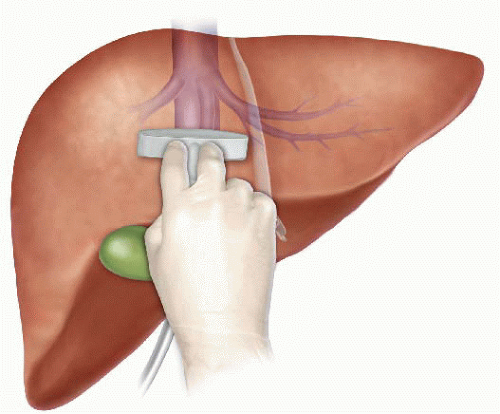

Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) is an extremely important tool when performing liver resections, specifically for patients with HCC and compromised liver function. IOUS allows for localization of the primary tumor, detection of additional tumors, satellite nodules, tumor thrombus, and define relationship with bilio-vascular structures within the liver. Finally, intraoperative US-guided injection of dye, such as methylene-blue, to portal branches can clearly define the margins of the segment supplied by the portal branch and facilitate safe anatomical resection.

The anterior approach to liver resection is a technique aimed at limiting tumor manipulation to avoid tumoral dissemination, decrease potential for blood loss caused by avulsion of hepatic veins, and decrease ischemia of the remnant liver caused by rotation of the hepatoduodenal ligament. This technique is described for large HCCs located in the right lobe, and was shown in a prospective, randomized trial to reduce frequency of massive bleeding, number of patients requiring blood transfusions, and improve overall survival in this setting. This approach can be challenging, and can be facilitated by the use of the hanging maneuver.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that blood loss and blood transfusion administration are significantly associated with both short-term perioperative, and long-term oncological results in patients undergoing resection for HCC. This has led surgeons to focus on limiting operative blood loss as a major objective in liver resection. Transfusion rates of <20 % are expected in most experienced liver surgery centers. Inflow occlusion, by the use of the Pringle Maneuver represents the most commonly performed method to limit blood loss. Cirrhotic patients can tolerate total clamping time of up to 90 min, and the benefit of reduced blood loss outweighs the risks of inflow occlusion, as long as ischemia periods of 15 min are separated by at least 5 min of reperfusion. Total ischemia time of above 120 min may be associated with postoperative liver dysfunction. Additional techniques aimed at reducing blood loss include total vascular isolation, by occluding the inferior vena cava (IVC) above and below the liver, however, the hemodynamic results of IVC occlusion may be significant, and this technique has a role mainly in tumors that are adjacent to the IVC or hepatic veins.

Anesthesiologists need to assure central venous pressure is low (below 5 mmHg) by limiting fluid administration, and use of diuretics, even at the expense 470 N. Lubezky et al. of low systemic pressure and use of inotropes. After completion of the resection, large amount of crystalloids can be administered to replenish losses during parenchymal dissection.

LAPAROSCOPIC RESECTIONS

Laparoscopic liver resections were shown to provide benefits of reduced surgical trauma, including a reduction in postoperative pain, incision-related morbidity, and shorten hospital stay. Some studies have demonstrated reduced operative bleeding with laparoscopy, attributed to the increased intra-abdominal pressure which reduces bleeding from the low-pressured hepatic veins. Additional potential benefits include a decrease in postoperative ascites and ascites-related wound complications, and fewer postoperative adhesions, which may be important in patients undergoing salvage liver transplantation. There has been a delay with the use of laparoscopy in the setting of liver cirrhosis, due to difficulties with hemostasis in the resection planes, and concerns for possible reduction of portal flow secondary to increased intraabdominal pressure. However, several recent studies have suggested that laparoscopic resection of HCC in patients with cirrhosis is safe and provides improved outcomes when compared to open resections.

Resections of small HCCs in anterior or left lateral segments are most amenable for laparoscopic resections. Larger resections, and resection of posterior-sector tumors are more challenging and should only be performed by very experienced surgeons. Long-term oncological outcomes of laparoscopic resections was shown to be equivalent to open resections on retrospective studies , but prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings. In recent years, robotic-assisted liver resections are being explored. Feasibility and safety of robotic-assisted surgery for HCC has been demonstrated in small non-randomized studies, but more experience is needed, and long-term oncologic results need to be studied, before widespread use of this technique will be recommended.

ALPPS: Associating Liver Partition with Portal vein ligation for Staged hepatectomy

The pre-operative options for inducing atrophy of the resected part and hypertrophy of the FLR, mainly PVE, were described earlier. Associating Liver Partition with Portal vein ligation for Staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) is another surgical option aimed to induce rapid hypertrophy of the FLR in patients with HCC. This technique involves a 2-stage procedure. In the first stage splitting of the liver along the resection plane and ligation of the portal vein is performed, and in the second stage, performed at least 2 weeks following the first stage, completion of the resection is performed. Patient safety is a major concern, and some studies have reported increased morbidity and mortality with the procedure. Few reports exist of this procedure in the setting of liver cirrhosis. Currently, the role of ALPPS in the setting of HCC and liver dysfunction needs to be better delineated before more widespread use is recommended.

Anatomia Cirúrgica Hepática

O Mapa Fundamental para Ressecções e Transplantes

Autor: Prof. Dr. Ozimo Gama

Categoria: Cirurgia Hepatobiliar / Anatomia Aplicada / Transplante Hepático Tempo de Leitura: 12 minutos

“Um bom conhecimento da anatomia do fígado é um pré-requisito para a cirurgia moderna do fígado.” — H. Bismuth

Introdução

O fígado, o maior órgão sólido do corpo humano (representando 2-3% do peso corporal), é uma estrutura de complexidade arquitetônica fascinante. Para o cirurgião geral, e imperativamente para o cirurgião hepatobiliar, o domínio da anatomia hepática transcende a memorização de nomes; trata-se de compreender as relações tridimensionais que ditam a segurança de uma hepatectomia e o sucesso de um transplante. Neste artigo, dissecaremos a anatomia hepática sob uma ótica cirúrgica, indo além da morfologia externa para explorar a segmentação funcional e as nuances vasculares vitais para a prática operatória de excelência.

1. Meios de Fixação e Mobilização Cirúrgica

O fígado é envolto pela cápsula de Glisson e peritônio, exceto na “área nua” diafragmática e no hilo. Seus ligamentos não são apenas estruturas de sustentação, mas marcos anatômicos cruciais para a mobilização segura do órgão:

-

Ligamentos Coronários e Triangulares: A mobilização destes permite a exposição da veia cava inferior (VCI) e das veias hepáticas.

-

Ligamento Venoso (Arantius): Remanescente do ducto venoso fetal. Sua dissecção é uma manobra chave. Ao isolá-lo, o cirurgião ganha acesso ao tronco das veias hepáticas esquerda e média, facilitando o controle vascular em hepatectomias esquerdas ou transplantes.

-

Ligamento Hepatocaval (Makuuchi): Uma estrutura fibrosa (por vezes contendo parênquima) que fixa o lobo caudado à veia cava. Sua divisão cuidadosa é obrigatória para expor a veia hepática direita e para a mobilização completa do lobo direito em transplantes intervivos.

2. A Revolução de Couinaud

A anatomia clássica, que dividia o fígado em lobos direito, esquerdo, quadrado e caudado baseada apenas em marcos externos (como o ligamento falciforme), é insuficiente para a cirurgia moderna. A verdadeira divisão funcional segue a Linha de Cantlie, um plano imaginário que vai do leito da vesícula biliar à veia cava inferior. Esta linha divide o fígado em metades funcionalmente independentes (Direita e Esquerda), cada uma com sua própria irrigação arterial, portal e drenagem biliar.

Adotamos a Segmentação de Couinaud (1954), que organiza o fígado em 8 segmentos baseados na distribuição das veias hepáticas e pedículos portais:

-

Fígado Direito (Setores Anterior e Posterior): Segmentos V, VIII (Anterior) e VI, VII (Posterior).

-

Fígado Esquerdo: Segmentos II, III (Lateral) e IV (Medial).

-

Lobo Caudado (Segmento I): Uma entidade autônoma. Localizado dorsalmente, recebe sangue de ambos os ramos portais (direito e esquerdo) e drena diretamente na VCI através de veias curtas. Esta drenagem direta confere ao caudado uma “proteção” relativa em casos de Síndrome de Budd-Chiari, onde ele frequentemente se hipertrofia.

3. O Hilo Hepático e a Tríade Portal

A dissecção do hilo exige precisão milimétrica, especialmente em transplantes com doador vivo (LDLT). As estruturas da tríade portal seguem uma organização anteroposterior constante que guia o cirurgião:

-

Ducto Biliar: Mais ventral (anterior) e lateral.

-

Artéria Hepática: Medial e na camada intermédia.

-

Veia Porta: A estrutura mais dorsal (posterior).

Variações Vasculares Importantes

-

Artéria Hepática: A anatomia “clássica” (artéria hepática comum saindo do tronco celíaco) está presente em apenas 60% dos casos. Variações críticas incluem a Artéria Hepática Direita Substituída (da Mesentérica Superior), que passa posterior à veia porta, e a Artéria Hepática Esquerda Substituída (da Gástrica Esquerda). O não reconhecimento pode levar à necrose do enxerto ou isquemia biliar.

-

Veia Porta: Variações na bifurcação, como a ausência do tronco principal da veia porta direita (trifurcação), exigem reconstruções complexas em transplantes.

4. Drenagem Venosa: O Escoamento

As três veias hepáticas principais (Direita, Média e Esquerda) correm nas fissuras intersegmentares:

-

Veia Hepática Direita (RHV): Drena o setor posterior. É a maior veia.

-

Veia Hepática Média (MHV): Corre na fissura principal (Linha de Cantlie). Fundamental para a drenagem dos segmentos V e VIII. Em transplantes de lobo direito, a gestão dos tributários da MHV é crítica para evitar congestão do enxerto.

-

Veias Acessórias: Cerca de metade da população possui veias hepáticas acessórias inferiores (drenando os segmentos VI e VII diretamente na cava). Se calibrosas (>5mm), devem ser reimplantadas para garantir a função do enxerto.

5. A Via Biliar e sua Vascularização: O “Tendão de Aquiles”

A anatomia biliar é a mais variável e propensa a complicações.

-

Irrigação Biliar: Diferente do parênquima, os ductos biliares extra-hepáticos são irrigados exclusivamente por um plexo arterial peribiliar (artérias das 3h e 9h), derivado principalmente da artéria hepática direita e retroduodenal.

-

Pérola Cirúrgica: Durante a captação do fígado, a dissecção excessiva do ducto biliar pode desvascularizá-lo, levando a estenoses isquêmicas tardias. Preservar a bainha peribiliar e o tecido hilar é mandatório.

6. A Vesícula Biliar e o Triângulo de Calot

Embora a colecistectomia seja um procedimento comum, ela exige respeito absoluto à anatomia. O Triângulo de Calot (delimitado pelo ducto cístico, ducto hepático comum e borda hepática) é a zona de segurança. A artéria cística deve ser identificada aqui. Variações, como um ducto cístico curto ou inserção no ducto direito, ou uma artéria hepática direita tortuosa (“Hump”) invadindo o triângulo, são armadilhas para o cirurgião desatento.

Conclusão

A cirurgia hepática evoluiu de ressecções em cunha não anatômicas para segmentectomias precisas e transplantes de doadores vivos. Essa evolução foi sustentada por um aprofundamento do conhecimento anatômico. Para o cirurgião em formação, o estudo exaustivo destas estruturas, suas variações e suas relações vasculares não é apenas acadêmico — é a base ética para oferecer segurança e cura aos pacientes portadores de doenças hepatobiliares.

Gostou ❔Nos deixe um comentário ✍️ , compartilhe em suas redes sociais e|ou mande sua dúvida pelo 💬 Chat On-line em nossa DM do Instagram.

Hashtags: #AnatomiaHepatica #CirurgiaDoFigado #TransplanteHepatico #Couinaud #CirurgiaHPB

Pringle Maneuver

After the first major hepatic resection, a left hepatic resection, carried out in 1888 by Carl Langenbuch, it took another 20 years before the first right hepatectomy was described by Walter Wendel in 1911. Three years before, in 1908, Hogarth Pringle provided the first description of a technique of vascular control, the portal triad clamping, nowadays known as the Pringle maneuver. Liver surgery has progressed rapidly since then. Modern surgical concepts and techniques, together with advances in anesthesiological care, intensive care medicine, perioperative imaging, and interventional radiology, together with multimodal oncological concepts, have resulted in fundamental changes. Perioperative outcome has improved significantly, and even major hepatic resections can be performed with morbidity and mortality rates of less than 45% and 4% respectively in highvolume liver surgery centers. Many liver surgeries performed routinely in specialized centers today were considered to be high-risk or nonresectable by most surgeons less than 1–2 decades ago.Interestingly, operative blood loss remains the most important predictor of postoperative morbidity and mortality, and therefore vascular control remains one of the most important aspects in liver surgery.

“Bleeding control is achieved by vascular control and optimized and careful parenchymal transection during liver surgery, and these two concepts are cross-linked.”

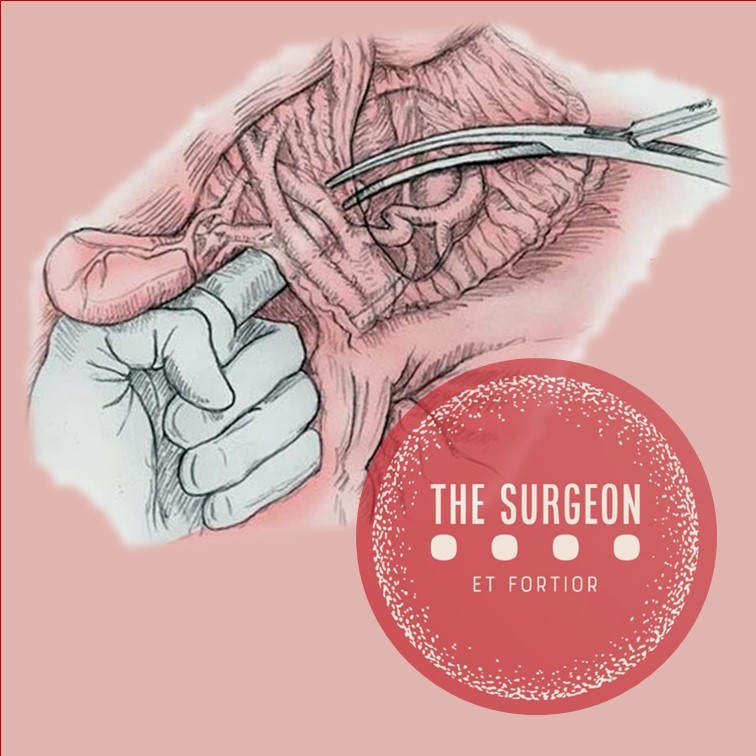

First described by Pringle in 1908, it has proven effective in decreasing haemorrhage during the resection of the liver tissue. It is frequently used, and it consists in temporarily occluding the hepatic artery and the portal vein, thus limiting the flow of blood into the liver, although this also results in an increased venous pressure in the mesenteric territory. Hemodynamic repercussion during the PM is rare because it only diminishes the venous return in 15% of cases. The cardiovascular system slightly increases the systemic vascular resistance as a compensatory response, thereby limiting the drop in the arterial pressure. Through the administration of crystalloids, it is possible to maintain hemodynamic stability.

In the 1990s, the PM was used continuously for 45 min and even up to an hour because the depth of the potential damage that could occur due to hepatic ischemia was not yet known. During the PM, the lack of oxygen affects all liver cells, especially Kupffer cells which represent the largest fixed macrophage mass. When these cells are deprived of oxygen, they are an endless source of production of the tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukins 1, 6, 8 and 10. IL 6 has been described as the cytokine that best correlates to postoperative complications. In order to mitigate the effects of continuous PM, intermittent clamping of the portal pedicle has been developed. This consists of occluding the pedicle for 15 min, removing the clamps for 5 min, and then starting the manoeuvre again. This intermittent passage of the hepatic tissue through ischemia and reperfusion shows the development of hepatic tolerance to the lack of oxygen with decreased cell damage. Greater ischemic tolerance to this intermittent manoeuvre increases the total time it can be used.

Recurrence after Repair of Incisional Hernia

The incidence of recurrence in incisional hernia prosthetic surgery is markedly lower than in direct plasties. Indeed after the autoplasties of the preprosthetic period, the recurrence rate ranged from 35% for ventral hernias. Chevrel and Flament, in 1990, reported on 1,033 patients who had undergone laparotomy. The recurrence rate at 10-year follow-up was 14–24% for patients treated without the use of prostheses but only 8.6% for those in whom a prosthesis was implanted. A similar incidence was reported by Chevrel in 1995: 18.3% recurrence without prostheses, 5.5% with prostheses. Likewise, Wantz, in 1991, noted a recurrence rate of 0–18.5% in prosthetic laparo-alloplasties.

At the European Hernia Society (EHS)-GREPA meeting in 1986, the recurrence rate without prostheses was reported to be between 7.2 and 17% whereas in patients who had been treated with a prosthesis the recurrence was between 1 and 5.8%. A case study published by Flament in 1999 showed a 5.6% recurrence rate for operations with prostheses placed behind the muscles and in front of the fascia, and a 3.6% of such figure consisted of a small-sized lateroprosthetic recurrence. These rates were in contrast to the 26.8% recurrence reported by other surgeons for operations without prostheses.

Studies of recurrence are, of course, influenced by the size of the initial defect and the length of follow-up. Nevertheless, it is beyond dispute that the use of prostheses is associated with a lower rate of recurrence independent of the nature of the incisional hernia. The factors that lead to relapse are recognisable in the original features of the ventral hernia, i.e. combined musculo-aponeurotic parietal involvement, septic complications in the first operation, the nature and appropriateness of treatment, the kind of prosthesis and its position. Also important is whether the surgery was an emergency case and the relation to occlusive phenomena, visceral damage

and whether these problems were addressed at the same time.

Obesity is also an important risk factor for recurrence. In addition to its association with a higher surgical complications rate, related to the high intraabdominal pressure, there are deficits in wound cicatrisation as well as respiratory and metabolic pathologies. In such patients, the laparoscopic approach is very useful to significantly reduce the onset of general and wall complications, and the data concerning recurrence are encouraging, ranging between 1 and 9% in the largest laparoscopic case studies. The important multicentric study of Heniford et al., in 2000, reported a recurrence rate of 3.4% after 23 months. In 2003, the same author, in a study with an average follow-up of 20 months (range 1–96) showed a recurrence rate of 4.7% for different, identifiable causes: intestinal iatrogenic injuries and mesh infection with its removal, insufficient fixation of the prosthesis and abdominal trauma in the first postoperative period.

The incidence of recurrence after laparoscopic treatment may also be related to general patient factors and to the onset of local complications, mistakes in opting for laparoscopic treatment and deficits in implanting and fixing the prosthesis. With respect to the latter, it is very important to allow a large overlap compared to the diameter of the defect. Long-term data analysis, with large case studies, is still needed to obtain detailed information about recurrence, and this is particularly true in the assessment of relatively new techniques.

Management of gallbladder cancer

Gallbladder cancer is uncommon disease, although it is not rare. Indeed, gallbladder cancer is the fifth most common gastrointestinal cancer and the most common biliary tract cancer in the United States. The incidence is 1.2 per 100,000 persons per year. It has historically been considered as an incu-rable malignancy with a dismal prognosis due to its propensity for early in-vasion to liver and dissemination to lymph nodes and peritoneal surfaces. Patients with gallbladder cancer usually present in one of three ways: (1) advanced unresectable cancer; (2) detection of suspicious lesion preoperatively and resectable after staging work-up; (3) incidental finding of cancer during or after cholecystectomy for benign disease.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Although, many studies have suggested improved survival in patients with early gallbladder cancer with radical surgery including en bloc resection of gallbladder fossa and regional lymphadenectomy, its role for those with advanced gallbladder cancer remains controversial. First, patients with more advanced disease often require more extensive resections than early stage tumors, and operative morbidity and mortality rates are higher. Second, the long-term outcomes after resection, in general, tend to be poorer; long-term survival after radical surgery has been reported only for patients with limited local and lymph node spread. Therefore, the indication of radical surgery should be limited to well-selected patients based on thorough preoperative and intra-operative staging and the extent of surgery should be determined based on the area of tumor involvement.

Surgical resection is warranted only for those who with locoregional disease without distant spread. Because of the limited sensitivity of current imaging modalities to detect metastatic lesions of gallbladder cancer, staging laparoscopy prior to proceeding to laparotomy is very useful to assess the

abdomen for evidence of discontinuous liver disease or peritoneal metastasis and to avoid unnecessary laparotomy. Weber et al. reported that 48% of patients with potentially resectable gallbladder cancer on preoperative imaging work-up were spared laparotomy by discovering unresectable disease by laparoscopy. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be avoided when a preoperative cancer is suspected because of the risk of violation of the plane between tumor and liver and the risk of port site seeding.

The goal of resection should always be complete extirpation with microscopic negative margins. Tumors beyond T2 are not cured by simple cholecystectomy and as with most of early gallbladder cancer, hepatic resection is always required. The extent of liver resection required depends upon whether involvement of major hepatic vessels, varies from segmental resection of segments IVb and V, at minimum to formal right hemihepatectomy or even right trisectionectomy. The right portal pedicle is at particular risk for advanced tumor located at the neck of gallbladder, and when such involvement is suspected, right hepatectomy is required. Bile duct resection and reconstruction is also required if tumor involved in bile duct. However, bile duct resection is associated with increased perioperative morbidity and it should be performed only if it is necessary to clear tumor; bile duct resection does not necessarily increase the lymph node yield.

Hepatic Surgery: Portal Vein Embolization

INTRODUCTION

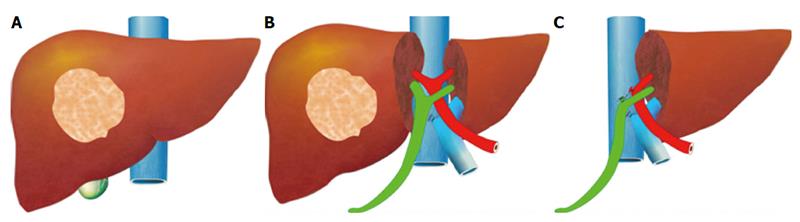

Portal vein Embolizations (PVE) is commonly used in the patients requiring extensive liver resection but have insufficient Future Liver Remanescent (FLR) volume on preoperative testing. The procedure involves occluding portal venous flow to the side of the liver with the lesion thereby redirecting portal flow to the contralateral side, in an attempt to cause hypertrophy and increase the volume of the FLR prior to hepatectomy.

PVE was first described by Kinoshita and later reported by Makuuchi as a technique to facilitate hepatic resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. The technique is now widely used by surgeons all over the world to optimize FLR volume before major liver resections.

PHYSIOPATHOLOGY

PVE works because the extrahepatic factors that induce liver hypertrophy are carried primarily by the portal vein and not the hepatic artery. The increase in FLR size seen after PVE is due to both clonal expansion and cellular hypertrophy, and the extent of post-embolization liver growth is generally proportional to the degree of portal flow diversion. The mechanism of liver regeneration after PVE is a complex phenomenon and is not fully understood. Although the exact trigger of liver regeneration remains unknown, several studies have identified periportal inflammation in the embolized liver as an important predictor of liver regeneration.

THECNICAL ASPECTS

PVE is technically feasible in 99% of the patients with low risk of complications. Studies have shown the FLR to increase by a median of 40–62% after a median of 34–37 days after PVE, and 72.2–80% of the patients are able to undergo resection as planned. It is generally indicated for patients being considered for right or extended right hepatectomy in the setting of a relatively small FLR. It is rarely required before extended left hepatectomy or left trisectionectomy, since the right posterior section (segments 6 and 7) comprises about 30% of total liver volume.

PVE is usually performed through percutaneous transhepatic access to the portal venous system, but there is considerable variability in technique between centers. The access route can be ipsilateral (portal access at the same side being resected) with retrograde embolization or contralateral (portal access through FLR) with antegrade embolization. The type of approach selected depends on a number of factors including operator preference, anatomic variability, type of resection planned, extent of embolization, and type of embolic agent used. Many authors prefer ipsilateral approach especially for right-sided tumors as this technique allows easy catheterization of segment 4 branches when they must be embolized and also minimizes the theoretic risk of injuring the FLR vasculature or bile ducts through a contralateral approach and potentially making a patient ineligible for surgery.

However, majority of the studies on contralateral PVE show it to be a safe technique with low complication rate. Di Stefano et al. reported a large series of contralateral PVE in 188 patients and described 12 complications (6.4%) only 6 of which could be related to access route and none precluded liver resection. Site of portal vein access can also change depending on the choice of embolic material selected which can include glue, Gelfoam, n-butyl-cyanoacrylate (NBC), different types and sizes of beads, alcohol, and nitinol plus. All agents have similar efficacy and there are no official recommendations for a particular type of agent.

RESULTS

Proponents of PVE believe that there should be very little or no tumor progression during the 4–6 week wait period for regeneration after PVE. Rapid growth of the FLR can be expected within the first 3–4 weeks after PVE and can continue till 6–8 weeks. Results from multiple studies suggest that 8–30% hypertrophy over 2–6 weeks can be expected with slower rates in cirrhotic patients. Most studies comparing outcomes after major hepatectomy with and without preoperative PVE report superior outcomes with PVE. Farges et al. demonstrated significantly less risk of postoperative complications, duration of intensive care unit, and hospital stay in patients with cirrhosis who underwent right hepatectomy after PVE compared to those who did not have preoperative PVE. The authors also reported no benefit of PVE in patients with a normal liver and FLR >30%. Abulkhir et al. reported results from a meta-analysis of 1088 patients undergoing PVE and showed a markedly lower incidence of Post Hepatectomy Liver Failure (PHLF) and death compared to series reporting outcomes after major hepatectomy in patients who did not undergo PVE. All patients had FLR volume increase, and 85% went on to have liver resection after PVE with a PHLF incidence of 2.5% and a surgical mortality of 0.8%. Several studies looking at the effect of systemic neoadjuvant chemotherapy on the degree of hypertrophy after PVE show no significant impact on liver regeneration and growth.

VOLUMETRIC RESPONSE

The volumetric response to PVE is also a very important factor in understanding the regenerative capacity of a patient’s liver and when used together with FLR volume can help identify patients at risk of poor postsurgical outcome. Ribero et al. demonstrated that the risk of PHLF was significantly higher not only in patients with FLR ≤ 20% but also in patients with normal liver who demonstrated ≤5% of FLR hypertrophy after PVE. The authors concluded that the degree of hypertrophy >10% in patients with severe underlying liver disease and >5% in patients with normal liver predicts a low risk of PHLF and post-resection mortality. Many authors do not routinely offer resection to patients with borderline FLR who demonstrate ≤5% hypertrophy after PVE.

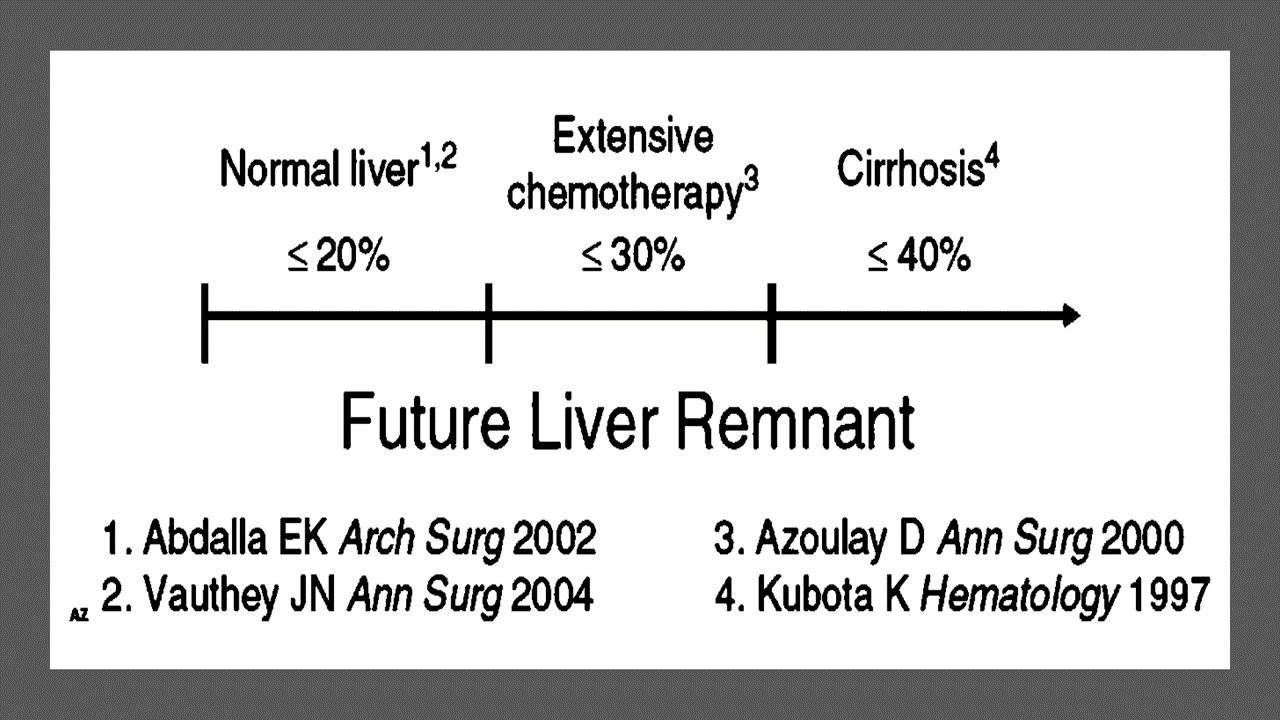

Predicting LIVER REMNANT Function

Careful analysis of outcome based on liver remnant volume stratified by underlying liver disease has led to recommendations regarding the safe limits of resection. The liver remnant to be left after resection is termed the future liver remnant (FLR). For patients with normal underlying liver, complications, extended hospital stay, admission to the intensive care unit, and hepatic insufficiency are rare when the standardized FLR is >20% of the TLV. For patients with tumor-related cholestasis or marked underlying liver disease, a 40% liver remnant is necessary to avoid cholestasis, fluid retention, and liver failure. Among patients who have been treated with preoperative systemic chemotherapy for more than 12 weeks, FLR >30% reduces the rate of postoperative liver insufficiency and subsequent mortality.

When the liver remnant is normal or has only mild disease, the volume of liver remnant can be measured directly and accurately with threedimensional computed tomography (CT) volumetry. However, inaccuracy may arise because the liver to be resected is often diseased, particularly in patients with cirrhosis or biliary obstruction. When multiple or large tumors occupy a large volume of the liver to be resected, subtracting tumor volumes from liver volume further decreases accuracy of CT volumetry. The calculated TLV, which has been derived from the association between body surface area (BSA) and liver size, provides a standard estimate of the TLV. The following formula is used:

TLV (cm3) = –794.41 + 1267.28 × BSA (square meters)

Thus, the standardized FLR (sFLR) volume calculation uses the measured FLR volume from CT volumetry as the numerator and the calculated TLV as the denominator: Standardized FLR (sFLR) = measured FLR volume/TLV Calculating the standardized TLV corrects the actual liver volume to the individual patient’s size and provides an individualized estimate of that patient’s postresection liver function. In the event of an inadequate FLR prior to major hepatectomy, preoperative liver preparation may include portal vein embolization (PVE).

Classroom: Principles of Hepatic Surgery

Videos of Surgical Procedures

This page provides links to prerecorded webcasts of surgical procedures. These are actual operations performed at medical centers in the Brazil. Please note that you cannot send in questions by email, though the webcast may say that you can, because you are not seeing these videos live. The videos open in a second window. If you have a pop-up blocker, you will need to disable it to view the programs.

Videos of Surgical Procedures

Surgical Management of Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a rare but lethal cancer arising from the bile duct epithelium. As a whole, CCA accounts for approximately 3 % of all gastrointestinal cancers. It is an aggressive disease with a high mortality rate. Unfortunately, a significant proportion of patients with CCA present with either unresectable or metastatic disease. In a retrospective review of 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma, Jarnagin et al. reported that 29 % of patients had either unresectable disease were unfit for surgery. Curative resection offers the best chance for longterm survival. Whereas palliation with surgical bypass was once the preferred surgical procedure even for resectable disease, aggressive surgical resection is now the standard.

Classroom: Surgical Management of Cholangiocarcinoma

Strangulation in GROIN HERNIAS

Importance

Declining Mortality Rates

In both the UK and the USA, the annual death rate due to inguinal and femoral hernias has significantly decreased over the past two to three decades. In the UK, deaths from these hernias declined by 22% to 55% between 1975 and 1990. Similarly, in the USA, the annual deaths per 100,000 population for patients with hernia and intestinal obstruction decreased from 5.1 in 1968 to 3.0 in 1988. For patients with obstructed inguinal hernias, 88% underwent surgery, with a remarkably low mortality rate of 0.05%. These improvements suggest that elective groin hernia surgery has played a crucial role in reducing overall mortality rates.

Elective Surgery and Strangulation Rates

Supporting this observation, the USA has lower rates of strangulation compared to the UK, possibly due to the threefold higher rate of elective hernia surgeries in the USA. Nevertheless, statistics indicate that the rate of elective hernia surgeries in the USA per 100,000 population decreased from 358 to 220 between 1975 and 1990, although this may be an artifact of data collection rather than a genuine decline.

Mortality Analysis from UK and Denmark Studies

During 1991–1992, the UK National Confidential Enquiry Into Perioperative Deaths investigated 210 deaths following inguinal hernia repair and 120 deaths following femoral hernia repair. This inquiry, which focuses on the quality of surgery, anesthesia, and perioperative care, found that many patients were elderly (45 were aged 80–89 years) and significantly infirm; 24 were ASA grade III and 21 ASA grade IV. The majority of postoperative mortality was attributed to preexisting cardiorespiratory issues.

A nationwide study in Denmark of 158 patients who died after acute groin hernia repair by Kjaergaard et al. also found that these patients were old (median age 83 years) and frail (>80% with significant comorbidity), with frequent delays in diagnosis and treatment. These findings highlight the need for high-quality care by experienced surgeons and anesthetists, especially for patients with high ASA grades.

Postoperative Care Recommendations

Postoperative care for these patients should occur in a high-dependency unit or intensive therapy unit. This might necessitate transferring selected patients to appropriate hospitals and facilities. Decisions about interventional surgery should be made in consultation with the relatives of extremely elderly, frail, or moribund patients, adopting a humane approach that may rule out surgery.

Emergency Admissions and Prioritization

Forty percent of patients with femoral hernias are admitted as emergency cases with strangulation or incarceration, while only 3% of patients with direct inguinal hernias present with strangulation. This disparity has implications for prioritizing patients on waiting lists when these hernias present electively in outpatient clinics.

Risk of Strangulation

A groin hernia is at its greatest risk of strangulation within three months of onset. For inguinal hernias, the cumulative probability of strangulation is 2.8% at three months after presentation, rising to 4.5% after two years. The risk is much higher for femoral hernias, with a 22% probability of strangulation at three months, rising to 45% at 21 months. Right-sided hernias have a higher strangulation rate than left-sided hernias, potentially due to anatomical differences in mesenteric attachment. The decline in hernia-related mortality in both the UK and USA underscores the importance of elective hernia surgery. Ensuring timely surgery, especially for high-risk femoral hernias, and providing high-quality perioperative care for elderly and frail patients are crucial steps in further reducing mortality and improving patient outcomes.

Evidence-Based Medicine

In a randomized trial, evaluating an expectative approach to minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias, Fitzgibbons et al. in the group of patients randomized to watchful waiting found a risk of an acute hernia episode of 1.8 in 1,000 patient years. In another trial, O’Dwyer and colleagues, randomizing patients with painless inguinal hernias to observation or operation, found two acute episodes in 80 patients randomized to observation. In both studies, a large percentage of patients randomized to nonoperative care were eventually operated due to symptoms. Neuhauser, who studied a population in Columbia where elective herniorrhaphy was virtually unobtainable, found an annual rate of strangulation of 0.29% for inguinal hernias.

Management of Strangulation

The diagnosis of hernias is primarily based on clinical symptoms and signs, supplemented by imaging studies when necessary. Pain at the hernia site is a constant symptom. In cases of obstruction with intestinal strangulation, patients may present with colicky abdominal pain, distension, vomiting, and constipation. Physical examination may reveal signs of dehydration, with or without central nervous system depression, especially in elderly patients with uremia, along with abdominal signs of intestinal obstruction.

Femoral hernias can be easily missed, particularly in obese women, making a thorough physical examination essential for an accurate diagnosis. However, physical examination alone is often insufficient to confirm the presence of a strangulated femoral hernia versus lymphadenopathy or a lymph node abscess. In such cases, urgent radiographic studies, such as ultrasound or CT scan, may be necessary.

The choice of incision depends on the type of hernia if the diagnosis is clear. When there is doubt, a half Pfannenstiel incision, 2 cm above the pubic ramus extending laterally, provides adequate access to all types of femoral or inguinal hernias. The fundus of the hernia sac is exposed, and an incision is made to assess the viability of its contents. If nonviability is detected, the transverse incision should be converted into a laparotomy incision, followed by the release of the constricting hernia ring, reduction of the sac’s contents, resection, and reanastomosis. Precautions must be taken to avoid contamination of the general peritoneal cavity by gangrenous bowel or intestinal contents.

In most cases, once the constriction of the hernia ring is released, circulation to the intestine is restored, and viability returns. The intestine that initially appears dusky or non-peristaltic may regain color with a short period of warming with damp packs. If viability is doubtful, resection should be performed. Resection rates are highest for femoral or recurrent inguinal hernias and lowest for simple inguinal hernias. Other organs, such as the bladder or omentum, should be resected as needed.

After peritoneal lavage and formal closure of the laparotomy incision, specific repair of the hernia should be performed. Prosthetic mesh should not be used in a contaminated operative field due to the high risk of wound infection. Hernia repair should follow the general principles of elective hernia repair. It is important to remember that in this predominantly frail and elderly patient group with a high postoperative mortality risk, the primary objective of the operation is to stop the vicious cycle of strangulation, with hernia repair being a secondary objective.

Key Point

The risk of an acute groin hernia episode is of particular relevance, when discussing indication for operation of painless or minimally symptomatic hernias. A sensible approach in groin hernias would be, in accordance with the guidelines from the European Hernia Society to advise a male patient, that the risk of an acute operation, with an easily reducible (“disappears when lying down”) inguinal hernia with little or no symptoms, is low and that the indication for operation in this instance is not absolute, but also inform, that usually the hernia after some time will cause symptoms, eventually leading to an operation. In contrast, female patients with a groin hernia, due to the high frequency of femoral hernias and a relatively high risk of acute hernia episodes, should usually be recommended an operation.

Wound Healing

There are many local and systemic factors that affect wound healing. The physician should be actively working to correct any abnormality that can prevent or slow wound healing.

Local Factors

A health care provider can improve wound healing by controlling local factors. He or she must clean the wound, debride it, and close it appropriately. Avulsion or crush wounds below under general management of wounds) need to be debrided until all nonviable tissue is removed. Grossly contaminated wounds should be cleaned as completely as possible to remove particulate matter (foreign bodies) and should be irrigated copiously. Bleeding must be controlled to prevent hematoma formation, which is an excellent medium for bacterial growth. Hematoma also separates wound edges, preventing the proper contact of tissues that is necessary for healing.

Radiation affects local wound healing by causing vasculitis, which leads to local hypoxia and ischemia. Hypoxia and ischemia impede healing by reducing the amount of nutrients and oxygen that are available at the wound site. Infection decreases the rate of wound healing and detrimentally affects proper granulation tissue formation, decreases oxygen delivery, and depletes the wound of needed nutrients. Care must be taken to clean the wound adequately. All wounds have some degree of contamination, if the body is able to control bacterial proliferation in a wound, that wound will heal. The use of cleansing agents (the simplest is soap and water) can help reduce contamination. A wound that contains the highly virulent streptococci species should not be closed. Physicians should keep in mind the potential for Clostridium tetani in wounds with devitalized tissue and use the proper prophylaxis.

Systemic Factors

In addition to controlling local factors, the physician must address systemic issues that can affect wound healing. Nutrition is an extremely important factor in wound healing. Patients need adequate nutrition to support protein synthesis, collagen formation, and metabolic energy for wound healing. Patients need adequate vitamins and nutrients to facilitate healing; folic acid is critical to the proper formation of collagen. Adequate fat intake is required for the absorption of vitamins D, A, K, and E. Vitamin K is essential for the

carboxylation of glutamate in the synthesis of clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X. Decreasing clotting factors can lead to hematoma formation and altered wound healing. Vitamin A increases the inflammatory response, increases collagen synthesis, and increases the influx of macrophages into a wound. Magnesium is required for protein synthesis, and zinc is a cofactor for RNA and DNA polymerase. Lack of any one of these vitamins or trace elements will adversely affect wound healing. Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus results in uncontrolled hyperglycemia, impairs wound healing, and alters collagen

formation. Hyperglycemia also inhibits fibroblast and endothelial cell proliferation within the wound. Medications will also affect wound healing. For example, steroids blunt the inflammatory response, decrease the available vitamin A in the wound, and alter the deposition and remodeling of collagen. Chronic illness (immune deficiency, cancer, uremia, liver disease, and jaundice) will predispose to infection, protein deficiency, and malnutrition, which, as noted previously, can affect wound healing. Smoking has a systemic effect by decreasing the oxygencarrying capacity of hemoglobin. Smoking may also decrease collagen formation within a wound. Hypoxia results in a decrease in oxygen delivery to a wound and retards healing.

Abdominal Surgical Anatomy

The abdomen is the lower part of the trunk below the diaphragm. Its walls surround a large cavity called the abdominal cavity. The abdominal cavity is much more extensive than what it appears from the outside. It extends upward deep to the costal margin up to the diaphragm and downward within the bony pelvis. Thus, a considerable part of the abdominal cavity is overlapped by the lower part of the thoracic cage above and by the bony pelvis below. The abdominal cavity is subdivided by the plane of the pelvic inlet into a larger upper part, i.e., the abdominal cavity proper, and a smaller lower part, i.e., the pelvic cavity. Clinically the importance of the abdomen is manifold. To the physician, the physical examination of the patient is never complete until he/she thoroughly examines the abdomen. To the surgeon, the abdomen remains an enigma because in number of cases the cause of abdominal pain and nature of abdominal lump remains inconclusive even after all possible investigations. To summarize, many branches of medicine such as general surgery and gastroenterology are all confined to the abdomen.