Specific Competence of Surgical Leadership

Surgeons are uniquely prepared to assume leadership roles because of their position in the operating room (OR). Whether they aspire to the title or not, each and every surgeon is a leader, at least within their surgical team. Their clinical responsibilities offer a rich variety of interpretations that prepare them for a broader role in health care leadership. They deal directly with patients and their families, both in and out of the hospital setting, seeing a perspective that traditional health care administrative leaders rarely experience. They work alongside other direct providers of health care, in varied settings, at night, on weekends, as well as during the typical workday. They understand supply-chain management as something more than lines on a spreadsheet.

The Challenges for a Surgical Leader

Surgeons prefer to lead, not to be led. Surgical training has traditionally emphasized independence, self-reliance, and a well-defined hierarchy as is required in the OR. However, this approach does not work well outside the OR doors. With colleagues, nurses, staff, and patients, they must develop a collaborative approach. Surgeons are entrusted with the responsibility of being the ultimate decision maker in the OR. While great qualities in a surgeon in the OR, it hinders their interactions with others. They have near-absolute authority in the OR, but struggle when switching to a persuasive style while in committees and participating in administrative activities. Most surgeons do not realize they are intimidating to their patients and staff. With patients, a surgeon needs to be empathetic and a good listener. A surgeon needs to slow the pace of the discussion so that the patient can understand and accept the information they are receiving. As perfectionists, surgeons demand a high level of performance of themselves. This sets them up for exhaustion and burnout, becoming actively disengaged, going through the motions, but empty on the inside. Given the many challenges surgeons face, it is difficult for them to understand the leadership role, given its complex demands.

Specific Competencies

Authority

Although teams and all team members provide health care should be allowed input, the team leader makes decisions. The leader must accept the responsibility of making decisions in the presence of all situations. They will have to deal with conflicting opinions and advice from their team, yet they must accept that they will be held accountable for the performance of their team. The surgeon–leader cannot take credit for successes while blaming failures on the team. Good teamwork and excellent communication do not relieve the leader of this responsibility.

Leadership Style

A surgeon often has a position of authority based on their titles or status in an organization that allows them to direct the actions of others. Leadership by this sort of mandate is termed “transactional leadership” and can be successful in accomplishing specific tasks. For example, a surgeon with transactional leadership skills can successfully lead a surgical team through an operation by requesting information and issuing directives. However, a leader will never win the hearts of the team in that manner. The team will not be committed and follow through unless they are empowered and feel they are truly heard. A transformational leader is one who inspires each team member to excel and to take action that supports the entire group. If the leader is successful in creating a genuine atmosphere of cooperation, less time will be spent giving orders and dealing with undercurrents of negativity. This atmosphere can be encouraged by taking the time to listen and understand the history behind its discussion. Blame should be avoided. This will allow the leader to understand the way an individual thinks and the group processes information to facilitate the introduction of change. While leadership style does not guarantee results, the leader’s style sets the stage for a great performance. At the same time, they should be genuine and transparent. This invites the team members to participate, creating an emotional connection. Leaders try to foster an environment where options are sought that meet everyone’s desires.

Conflict Management

Conflict is pervasive, even in healthy, well-run organizations and is not inherently bad. Whether conflict binds an organization together or divides it into factions depends on whether it is constructive or destructive. A good leader needs to know that there are four essential truths about conflict. It is inevitable, it involves costs and risks, the strategies we develop to deal with the conflict can be more damaging than the conflict itself, and conflict can be permanent if not addressed. The leader must recognize the type of conflict that exists and deal with the conflict appropriately. Constructive discussion and debate can result in better decision making by forcing the leader to consider other ideas and perspectives. This dialog is especially helpful when the leader respects the knowledge and opinions of team members with education, experience, and perspective different from the leader’s. Honesty, respect, transparency, communication, and flexibility are all elements that a leader can use to foster cohesion while promoting individual opinion. The leader can create an environment that allows creative thinking, mutual problem solving, and negotiation. These are the hallmarks of a productive conflict. Conflict is viewed as an opportunity, instead of something to be avoided.

Communication Skills

Communication is the primary tool of a successful leader. On important topics, it is incumbent on the leader to be articulate, clear, and compelling. Their influence, power, and credibility come from their ability to communicate. Research has identified the primary skills of an effective communicator. They are set out in the LARSQ model: Listening, Awareness of Emotions, Reframing, Summarizing, and Questions. These are not set in a particular order, but rather should move among each other freely. In a significant or critical conversation, it is important for a leader to listen on multiple levels. The message, body language, and tone of voice all convey meaning. You cannot interrupt or over-talk the other side. They need an opportunity to get their entire message out. Two techniques that enhance listening include pausing and the echo statement. Pausing before speaking allows the other conversant time to process what they have said to make sure the statement is complete and accurate. Echo statements reflect that you have heard what has been said and focuses on a particular aspect needing clarification. Good listening skills assure that the leader can get feedback that is necessary for success.

Vision, Strategy, Tactics, and Goals

One of the major tasks of a leader is to provide a compelling vision, an overarching idea. Vision gives people a sense of belonging. It provides them with a professional identity, attracts commitment, and produces an emotional investment. A leader implements vision by developing strategy that focuses on specific outcomes that move the organization in the direction of the vision. Strategy begins with sorting through the available choices and prioritizing resources. Through clarification, it is possible to set direction. Deficits will become apparent and a leader will want to find new solutions to compensate for those shortfalls. For example, the vision of a hospital is to become a world class health care delivery system. Strategies might include expanding facilities, improving patient satisfaction, giving the highest quality of care, shortening length of hospital stay with minimal readmissions, decreased mortality, and a reduction in the overall costs of health care. Tactics are specific behaviors that support the strategy with the aim to achieve success. Tactics for improving patient satisfaction may include reduced waiting time, spending more time with patients, taking time to communicate in a manner that the patient understands, responding faster to patient calls, etc. These tactics will then allow a leader to develop quantitative goals. Patient satisfaction can be measured. The surgical leader can then construct goals around each tactic, such as increasing satisfaction in specific areas. This information allows a surgical leader to identify barriers and they can take steps to remedy problem areas. This analysis helps a leader find the weakest links in their strategies as they continue toward achieving the vision.

Change Management

The world of health care is in continuous change. The intense rate of political, technical, and administrative change may outpace an individual’s and institution’s ability to adapt. Twenty-first century health care leaders face contradictory demands. They must navigate between competing forces. Leaders must traverse a track record of success with the ability to admit error. They also must maintain visionary ideas with pragmatic results. Individual accountability should be encouraged, while at the same time facilitating teamwork. Most leaders do not understand the change process. There are practical and psychological aspects to change. From an institutional perspective, we know that when 5% of the group begins to change, it affects the entire group. When 20% of a group embraces change, the change is unstoppable.

Succession Planning and Continuous Learning

An often-overlooked area of leadership is planning for human capital movement. As health care professionals retire, take leaves of absences, and move locations, turmoil can erupt in the vacuum. Leaders should regularly be engaging in activities to foster a seamless passing of institutional knowledge to the next generation. They also should seek to maintain continuity to the organization. Ways to accomplish this include senior leaders actively exposing younger colleagues to critical decisions, problem solving, increased authority, and change management. Leaders should identify promising future leaders, give early feedback for areas of improvement, and direct them toward available upward career tracks. Mentoring and coaching help prepare the younger colleagues for the challenges the institution is facing. Teaching success at all levels of leadership helps create sustainable high performance.

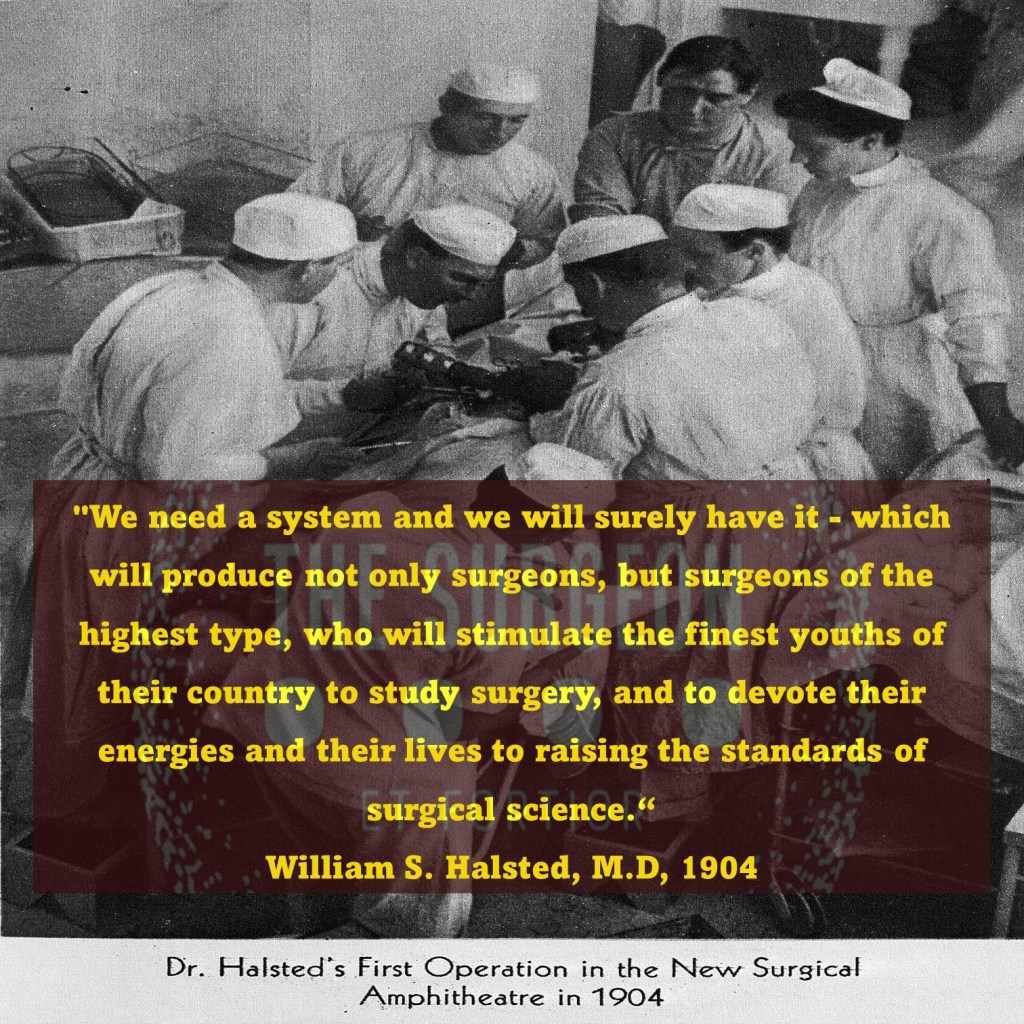

“Not Only SURGEONS…”

SURGERY, A NOBLE PROFESSION

Surgery is, indeed, one of the noblest of professions. Here is how Dictionary defines the word noble: 1) possessing outstanding qualities such as eminence, dignity; 2) having power of transmitting by inheritance; 3) indicating superiority or commanding excellence of mind, character, or high ideals or morals. These three attributes befit the profession of surgery. Over centuries, the surgical profession has set the standards of ethical and humane practice. Surgeons have made magnificent contributions in education, clinical care, and science. Their landmark accomplishments in surgical science and innovations in operative technique have revolutionized surgical care, saved countless lives, and significantly improved longevity and the quality of human life. Generations of surgeons have developed their craft and passed it on to succeeding generations, as they have to me and to each one of you, to take into the future.

Beyond its scientific and technical contributions, surgery is uniquely fulfilling as a profession. It has disciplined itself over the centuries and dedicated its practice to the best welfare of all human beings. In return, it has been accorded the respect of society, of other professions, and of policy makers. Its conservative stance has served it well and has been the reason for its constancy and consistency. At the beginning of the 21st century, however, profound changes are taking place at all levels and at a dizzying pace, providing both challenges and opportunities to the surgical profession. These changes are occurring on a global level, on the national level, in science and technology, in healthcare, and in surgical education and practice.

To retain its leadership position in innovation and its attractiveness as a career choice for students, surgery must evolve with the times. It is my belief that surgery needs to introduce changes to create new priorities in clinical practice, education, and research; to increase the morale and prestige of surgeons; and to preserve general surgery as a profession. I am reminded of a Chinese aphorism that says, “You cannot prevent the birds of unhappiness from flying over your head, but you can prevent them from building a nest in your hair.”

ADVANCES IN SCIENCE

The coalescence of major advances in science and technology made the end of the 20th century unique in human history. Notable among the achievements are the development of microchips and miniaturization, which fueled the explosion in information technology. The structure of the human genome is nearly completely elucidated, ushering in the genomic era in which genetic information will be used to predict, on an individual basis, susceptibility to disease and responsiveness to drug therapy. The field of nanotechnology allows scientists to work at a resolution of less than one nanometer, the size of the atom. By comparison, the DNA molecule is 2.5 nanometers.

In the last 50 years, biomedical research became increasingly reductionist, turning physiologists and anatomists into molecular biologists. As a result, two basic science fields—integrative physiology and gross anatomy—now have a lower standing in medical education and surgical science than they once did. Surgery and surgical departments can and possibly should claim these fields, but the window of opportunity is narrow. Research is now moving back from discipline-based reductionist science to multidisciplinary science of complexity, in which biomedical scientists work side by side with engineers, mathematicians, and bioinformatists. The ability of high-speed computers to quickly process tens of millions of pieces of data now allows for data-driven rather than hypothesis-based research. This collaboration among different disciplines has already been successful.

TRANSFORMATION OF HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

During the past 75 years, we have seen the entire healthcare system undergo a profound transformation. In the 1930s and for a considerable period thereafter, medical practice was fee-for-service, the doctor–patient relationship was strong, and the physician perceived himself or herself as being responsible nearly exclusively to his or her individual patients. The texture of medical practice started to change when the federal government became involved in the provision of healthcare in 1965. The committee on “Crossing the Quality Chasm” identified six key attributes of the 21st-century healthcare system. It must be:

- Safe, avoiding injuries to patients;

- Effective, providing services based on scientific knowledge;

- Patient-oriented, respectful of and responsive to individual patients’ needs, values, and preferences;

- Timely, reducing waits, eliminating harmful delays for both care receiver and caregiver;

- Efficient, avoiding wasted equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy;

- Equitable, providing equal care across genders, ethnicities, geographic locations, and socioeconomic strata;

No one knows at present what this 21st-century healthcare system will look like. While care in the old system was reactive, in the new system it will be proactive. The “find it, fix it” approach of the old system will be replaced by a “predict it, prevent it, and if you cannot prevent it, fix it” approach. Sporadic intervention, provided only when patients present with illness, will give way to a system in which physicians and other healthcare providers plan 1-, 5-, and 10-year care programs for each patient. Care will be more interactive, with patients taking a more important role in their own care. The technology-oriented system will become a system that provides graded intervention. Delivery systems will not be fractionated but integrated. Even more importantly, care will not be based simply on experience and clinical impression but on evidence of proven outcome measures. If the old system was cost-insensitive, the new system will be cost-sensitive.

SURGICAL PRACTICE

There are many reasons for the declining interest in general surgery, some of which parallel reasons for the drop in medical school applicants in general. One problem specific to surgery is that medical students are given less and less exposure to surgery, due to the shortening of required surgical rotations. Most important, however, is their perception that the life of the surgical resident is stressful, the work hours too long, and the time for personal and family needs inadequate. The workload of the surgical resident over the years has increased significantly both in amount and intensity, without concomitant increase in the number of residents and at a time when hospitals have significantly reduced the support personnel on the surgical ward and in the operating rooms. Students graduating with debts close to $100,000 simply find the years of training in surgery too long, followed by uncertain practice income after graduation.

From several recent studies, lifestyle is the critical and most pressing issue in surgical residency. Some studies have also shown that the best students tend to select specialties that provide controllable lifestyles, such as radiology, dermatology, and ophthalmology. We have a problem not only in the declining number of students applying for surgical training but also in the declining quality of those who do apply. In a preliminary survey of 153 responding general surgery programs, we found that attrition (i.e., categorical residents leaving the training programs) occurred at a rate of 13% to 19% in the last 5 years. In 2001, 46% of those leaving general surgery training programs cited lifestyle as the major reason.

Unless these trends are reversed, general surgery as a specialty is threatened, and a future shortage of general surgeons is inevitable. I know that the Council of the American Surgical Association is most concerned about the crisis in general surgery. We must do a better job of communicating to students and residents that the practice of surgery is as rewarding as ever and full of opportunities in this new era. Innovations in minimal access and computer-assisted surgery and simulation technology provide exciting new possibilities in surgical training. We must also look very carefully at the demands of surgical residency and improve the life of residents without compromising their surgical experience. Unless we deal with work hours and quality of life issues, we are likely to see continuing decline in the interest of medical students in surgical training.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the noble profession of surgery must rise to meet numerous challenges as the world in which it operates continues to undergo profound change. These challenges represent opportunities for the profession to develop an international perspective and a global outreach and to address the growing needs of an aging population undergoing major demographic and workforce shifts. The leadership of American surgery has a unique role to play in the formulation of a new healthcare system for the 21st century. This task will require commitment to quality of care and patient safety, and it will depend on harnessing the trust and support of the American public. Advances in science and technology—particularly in minimal access surgery, robotics, and simulation technology—provide unprecedented opportunity for surgeons to continue to make landmark contributions that will improve surgical care and the human condition. I believe it is also crucially important that we train surgeon-scientists who will keep surgery at the cutting edge in the genomic and bioinformatics era. Ours is a noble profession imbued with eminence, dignity, high ideals, and ethical values. It has a rich and proud heritage… and I quote, “The highest intellects, like the tops of mountains, are the first to catch and reflect the dawn.”

Source: Lecture from Haile T. Debas, MD (UCSF School of Medicine, San Francisco, California) Presented at the 122nd Annual Meeting of the American Surgical Association, April 25, 2002, The Homestead, Hot Springs, Virginia.

Aprendendo a Aprender

As oportunidades de aprendizado nos são oferecidas a cada momento, o tempo todo. Aprendemos toda vez que nos damos ao trabalho de pensar sobre o que determinado momento nos trouxe, o que nos ensinou que ainda não sabíamos, o que nos mostrou a respeito dos outros e de nós mesmos, e que antes ignorávamos. E esse processo é tão longo quanto a vida.

O caminho mais curto e certo para a estagnação é perder a disposição de aprender, seja pela arrogância de achar que já sabe tudo, seja pela enganosa convicção de que é cedo demais para adquirir tal conhecimento. A acomodação é outra inimiga do aprendizado, pois paralisa o segundo requisito necessário para que ele ocorra: o esforço. É preciso esforçar-se para manter a mente aberta ao novo, para não se deixar limitar pelos preconceitos e opiniões preconcebidas. E também é preciso esforço para ampliar as oportunidades de aprendizado, reservando tempo para as leituras, para as conversas e atividades instrutivas, para se atualizar e aprofundar seu conhecimento.

Não refiro apenas ao conhecimento necessário à sua profissão, mas a todos os aspectos de sua vida, por exemplo, conhecer mais a fundo sua família – acreditar que já sabemos tudo sobre nossos familiares é um erro fatal em qualquer tipo de relacionamento. Outro equívoco é negligenciar o autoconhecimento: uma série de frustrações, angústias e motivações. Conhecê-las também é um aprendizado constante, talvez o mais árduo de todos.

“Todas me pareceram tão cheias de si”, contou Sócrates, “tão seguras de suas verdades e certezas que, se sou de fato mais sábio do que elas, é pela simples razão de que sei de que não sei aquilo que elas acham que sabem”. Como nos sugere o filósofo com toda a sua perspicácia e sabedoria, a admissão de que ainda temos muito a aprender é o primeiro passo para transformarmos nossa vida em um constante aprendizado. A consciência desse fato enriquece nossas vidas, ampara nossas escolhas e direciona nossas ações. A importância de aprender sempre é tamanha que Stephen R. Covey, autor do best-seller Os 7 Hábitos das Pessoas Altamente Eficazes e 8° Hábito, a coloca entre as quatro necessidades básicas do ser humano – as demais serão afetadas.

O aprendizado, porém, está presente em todas: aprendemos a viver, a amar, a deixar um legado e, até mesmo, aprendemos a aprender.

Surgeons and Performance

SURGEONS ARE HIGH PERFORMANCE ATHLETES

In a 2011 New Yorker article, Dr. Atul Gawande explored the idea that surgeons should consider a performance coach. Like athletes, he reasons, surgeons rely on complex physical movements to achieve their goals. Guidance and refinement by a trained eye could improve their performance.

Surgical coaching is a controversial topic (one which colleagues and I are actively investigating). But in the years following Dr. Gawande’s article, this idea opened the door to a broader concept: the “surgeon athlete.” An “athlete” is one whose performance depends on a carefully choreographed interplay between mind and body: heightened focus and anticipation along with quick decision-making and coordination. Combined with the reliance on teamwork and requisite stamina, this is wholly within the job description of a surgeon. Many surgeons are likely to find this concept silly. But our profession has imprudently encouraged surgical trainees to disregard the critical fine-tuning of their minds and bodies. We demand perfection, stamina, and encyclopedic knowledge, while discouraging the healthy habits that improve performance. Ironically, the sports world is more advanced in applying science to their training. And by ignoring this indisputable science, we are really hurting our patients. Because in order to best take care of them, we need to first take care of ourselves.

The “GOOD” Surgeon

Surgery is an extremely enjoyable, intellectually demanding and satisfying career, and many more people apply to become surgeons each year than there are available places.

Those who are successful have to be ready not just to learn a great deal, but have the right kind of personality for the job.

Is a surgical career right for you?

Read the link…

THE GOOD SURGEON

O TEMPLO DO CIRURGIÃO.

Templo (do latim templum, “local sagrado”) é uma estrutura arquitetônica dedicada ao serviço religioso. O termo também pode ser usado em sentido figurado. Neste sentido, é o reflexo do mundo divino, a habitação de Deus sobre a terra, o lugar da Presença Real. É o resumo do macrocosmo e também a imagem do microcosmo: ‘o corpo é o templo do Espírito Santo’ (I, Coríntios, 6, 19).

Dos locais especiais, O corpo humano (morada da alma), a Cavidade Peritoneal e o Bloco Cirúrgico, se bem analisados, são muito semelhantes e merecem atitudes e comportamentos respeitáveis. O Templo, em todos os credos, induz à meditação, absoluto silêncio tentando ouvir o Ser Supremo. A cavidade peritoneal | abdominal , espaço imaculado da homeostase, quando injuriada, reage gritando em dor, implorando uma precoce e efetiva ação terapêutica.

O Bloco Cirúrgico, abrigo momentâneo do indivíduo solitário, que mudo e quase morto de medo, recorre à prece implorando a troca do acidente, da complicação, da recorrência, da seqüela, da mutilação, da iatrogenia e do risco de óbito pela agressiva e controlada intervenção que lhe restaure a saúde, patrimônio magno de todo ser vivo.

O Bloco Cirúrgico clama por respeito ao paciente cirúrgico, antes mesmo de ser tomado por local banal, misturando condutas vulgares, atitudes menores, desvio de comportamento e propósitos secundários. Trabalhar no Bloco Cirúrgico significa buscar a perfeição técnica, revivendo os ensinamentos de William Stewart Halsted , precursor da arte de operar, dissecando para facilitar, pinçando e ligando um vaso sangüíneo, removendo tecido macerado, evitando corpos estranhos e reduzindo espaço vazio, numa síntese feita com a ansiedade e vontade da primeira e a necessidade e experiência da última.

Mas, se a cirurgia e o cirurgião vêm sofrendo grande evolução, técnica a primeira e científica o segundo, desde o início do século, a imagem que todo doente faz persiste numa simbiose entre mitos e verdades. A cirurgia significa enfrentar ambiente desconhecido chamado “sala de cirurgia” onde a fobia ganha espaço rumo ao infinito. O medo ainda prepondera em muitos.

A confiança neste momento além de um reconhecimento é um troféu que o cirurgião recebe dos pacientes e seus familiares. Tanto a CONFIANÇA quanto a SEGURANÇA têm que ser preservadas a qualquer custo. Não podem correr o risco de serem corroídas por palavras e atitudes de qualquer membro da equipe cirúrgica. Não foi tarefa fácil transformar, para a população, o ato cirúrgico numa atividade científica, indispensável, útil e por demais segura. Da conquista da cirurgia, como excelente arma terapêutica para a manutenção de um alto padrão de qualidade técnica, resta a responsabilidade dos cirurgiões, os herdeiros do suor e sangue, que se iniciou com o trabalho desenvolvido por Billroth, Lister, Halsted, Moyniham, Kocher e uma legião de figuras humanas dignas do maior respeito, admiração e gratidão universal.

No ato operatório os pacientes SÃO TODOS SEMELHANTES EM SUAS DIFERENÇAS, desde a afecção, ao prognóstico, ao caráter da cirurgia e especialmente sua relação com o ato operatório. Logo, o cirurgião tem por dever de ofício entrar no bloco cirúrgico com esperança e não deve sair com dúvida. Nosso trabalho é de equipe, cada um contribui com uma parcela, maior ou menor, para a concretização do todo, do ato cirúrgico por completo, com muita dedicação, profissionalismo e sabedoria. Toda tarefa, da limpeza do chão ao ato de operar, num crescendo, se faz em função de cada um e em benefício da maioria, o mais perfeito possível e de uma só vez, quase sempre sem oportunidade de repetição e previsão de término.

O trabalho do CIRURGIÃO é feito com carinho, muita dignidade, humildade e executado em função da alegria do resultado obtido aliado a dimensão ética do dever cumprido que transcende a sua existência. A vida do cirurgião se materializa no ato operatório e o bloco cirúrgico, palco do nosso trabalho não tolera e jamais permite atitudes menores, inferiores, ambas prejudiciais a todos os pacientes e a cada cirurgião. Como ambiente de trabalho de uma equipe diversificada, precisamos manter, a todo custo, o controle de qualidade, eficiência, eficácia e efetividade técnina associados aos mais altos valores ético, pois lidamos com o que há de mais precioso da criação divina na Terra: O SER HUMANO.

“Tem presença de Deus, como já a tens. Ontem estive com um doente, um doente a quem quero com todo o meu coração de Pai, e compreendo o grande trabalho sacerdotal que os médicos levam a cabo. Mas não se ponham orgulhosos, porque todas as almas são sacerdotais. Devem pôr em prática esse sacerdócio! Ao lavares as mãos, ao vestires a bata, ao calçares as luvas, pensa em Deus, e pensa nesse sacerdócio real de que fala São Pedro, e então não se te meterá a rotina: farás bem aos corpos e às almas” São Josemaria Escriva

A “PROFISSÃO” CIRÚRGICA

“A arte de curar vem do coração e da mente mais do que das mãos.” – Hipócrates

“A arte de curar vem do coração e da mente mais do que das mãos.” – Hipócrates

Na complexa tapeçaria da sociedade moderna, as profissões desempenham papéis fundamentais na organização dos serviços necessários ao bem-estar coletivo. Definida pelo American College of Surgeons, uma profissão é um campo onde a maestria de um corpo complexo de conhecimento e habilidades é essencial. É uma vocação em que o conhecimento científico ou a prática de uma arte, fundamentada nesse conhecimento, é empregada em benefício dos outros. O compromisso com a competência, a integridade e a moralidade forma a base de um contrato social entre a profissão e a sociedade, que concede à profissão um monopólio sobre o uso de seu conhecimento, considerável autonomia na prática e o privilégio da auto-regulação. Em troca, a profissão deve prestar contas a quem serve e à sociedade como um todo.

Os Elementos Essenciais da Profissão

No cerne de toda profissão estão quatro elementos fundamentais:

- Monopólio do Conhecimento Especializado: Profissionais detêm o direito exclusivo de utilizar conhecimentos e habilidades especializados, o que lhes confere uma posição única na sociedade.

- Autonomia e Auto-Regulação: Em troca deste monopólio, profissionais desfrutam de uma relativa autonomia na prática e são responsáveis pela sua própria regulação.

- Serviço Altruísta: A profissão deve servir tanto indivíduos quanto a sociedade de forma altruísta, colocando o bem-estar do paciente acima de outros interesses.

- Responsabilidade pela Manutenção e Expansão do Conhecimento: Profissionais são responsáveis por atualizar e expandir continuamente seu conhecimento e habilidades.

O Que é Profissionalismo?

Profissionalismo descreve as qualidades cognitivas, morais e colegiais de um profissional. É o conjunto de razões pelas quais um pai se orgulha de dizer que seu filho é um médico e cirurgião. Profissionalismo é mais do que apenas conhecimento técnico; é uma combinação de ética, respeito e dedicação ao ofício e ao paciente.

Por Que Precisamos de um Código de Conduta Profissional?

A confiança é o alicerce da prática cirúrgica. O Código de Conduta Profissional esclarece a relação entre a profissão cirúrgica e a sociedade que serve, frequentemente referido como contrato social. Para os pacientes, o código cristaliza o compromisso da comunidade cirúrgica em relação aos indivíduos e suas comunidades. A confiança é construída, tijolo por tijolo.

O Código de Conduta Profissional

O Código de Conduta Profissional aplica os princípios gerais do profissionalismo à prática cirúrgica e serve como a fundação sobre a qual os privilégios profissionais e a confiança dos pacientes e do público são conquistados. Durante o cuidado pré-operatório, intraoperatório e pós-operatório, os cirurgiões têm a responsabilidade de:

- Advogar Eficazmente pelos interesses dos pacientes.

- Divulgar Opções Terapêuticas incluindo seus riscos e benefícios.

- Divulgar e Resolver Conflitos de Interesse que possam influenciar as decisões de cuidado.

- Ser Sensível e Respeitoso com os pacientes, compreendendo sua vulnerabilidade durante o período perioperatório.

- Divulgar Completamente Eventos Adversos e Erros Médicos.

- Reconhecer Necessidades Psicológicas, Sociais, Culturais e Espirituais dos pacientes.

- Incorporar Cuidados Especiais para Pacientes Terminais.

- Reconhecer e Apoiar as Necessidades das Famílias dos Pacientes.

- Respeitar o Conhecimento, Dignidade e Perspectiva de outros profissionais de saúde.

A Necessidade do Código de Profissionalismo para Cirurgiões

Procedimentos cirúrgicos são experiências extremas que impactam os pacientes fisiológica, psicológica e socialmente. Quando os pacientes se submetem a uma experiência cirúrgica, devem confiar que o cirurgião colocará seu bem-estar acima de todas as outras considerações. O código escrito ajuda a reforçar esses valores, garantindo que a confiança e o compromisso sejam mantidos.

Princípios Fundamentais do Código de Conduta Profissional

- Primazia do Bem-Estar do Paciente: Os interesses do paciente sempre devem vir em primeiro lugar. O altruísmo é central para esse conceito, e é o altruísmo do cirurgião que fomenta a confiança na relação médico-paciente.

- Autonomia do Paciente: Pacientes devem entender e tomar suas próprias decisões informadas sobre o tratamento. Os médicos devem ser honestos para que os pacientes façam escolhas educadas, garantindo que essas decisões estejam alinhadas com práticas éticas.

- Justiça Social: Como médicos, devemos advogar pelos pacientes individuais enquanto promovemos a saúde do sistema de saúde como um todo. Precisamos equilibrar as necessidades dos pacientes (autonomia) sem desviar recursos escassos que beneficiariam a sociedade (justiça social).

“Não há maior coisa a ser conquistada do que a confiança dos pacientes e da sociedade, pois ela é a base sobre a qual construímos nossas práticas e nossa profissão.” – William Osler

Survival Guide for SURGERY ROUND

SURGERY ROUND

Medical students are often attached to the various services. They can provide a significant contribution to patient care. However, their work requires supervision by the surgical intern/resident who takes primary clinical responsibility. Subinterns are senior medical students who are seeking additional clinical experience. Their assistance is needed and appreciated, but again, close supervision of their clinical responsibilities by the intern/resident is mandatory.Outside reading is recommended, including textbooks, reference sources, and monthly journals.Eating is prohibited in patient care areas.Maintain patient confidentiality at all times.At conferences use only patient initials in presentations; and speak carefully and respectfully on work rounds.

PRINCIPLES

1. Always be punctual (this includes ward rounds, operating room, clinics, conferences, morbidity and mortality). Personal appearance is very important. Maintain a high standard including clean shirt and tie (or equivalent) and a clean white coat. The day begins early. Be ready with all the data to start rounds with the senior resident or chief resident. Be sure to provide enough time each morning to examine your patients before rounds.

ABOUT NOTES

2.Aim to get all of your chart notes written as soon as possible; this will greatly increase your effi ciency during the day. Sign and print your name, and include your beeper number, date, and time. Progress notes on patients are required daily. Surgical progress notes should be succinct and accurate, briefl y summarizing the patient’s clinical status and plan of management. Someone unfamiliar with the case should be able to get a good understanding of the patient’s condition from one or two notes. Operative consent is obtained after admitting the patient, performing the history and physical examination, discussing the risks, benefi ts, and alternatives of the procedure(s), and having the patient’s nurse sign the consent with the patient. If you are unaware of the risks and benefi ts of a procedure, discuss this with the service chief resident. Blood transfusion attestation forms need to be signed by the counseling physician before each surgical procedure.

OPERATING ROOM

3. Arrive in the operating room with the patient and before the attending physician or chief resident. Make sure that the charts and all of the relevant x-rays are in the operating room. Make sure that the x-rays are on the x-ray view box prior to the commencement of the case. The intern or resident performing the case should be familiar with the patient’s history and physical exam, current medications, and comorbidities, and be familiar with the principles of the operation prior to arriving in the operating room. Make it a habit to introduce yourself to the patient before the operation. It is mandatory that the surgical resident involved with a case in the operating room attend the start of the case punctually. Scheduled operative cases do not necessarily occur at the listed time. For this reason, it is necessary to check with the operating room front desk frequently. Do not rely on being paged. Conduct in the operating room includes assisting with the preoperative positioning and preparation of the patient; this includes shaving, catheterization, protection of pressure points, and thromboembolism protection. The resident should escort the patient from the operating room to the intensive care unit (ICU) or the postanesthetic care unit with the anesthesiologists. The operating surgeon is responsible for dictating the case. The resident must record all cases performed. For cases admitted to the surgery ICU, a hand-over to the surgery ICU resident is mandatory.This includes discussing all the preoperative assessment, operative details, and postoperative management of the case with the ICU resident.

ROUNDS

4. Signing out to cross-cover services must be performed in a meticulous and careful fashion. All patients should be discussed between the surgical intern and the cross-covering intern to cover all potential problems. A sign-out list containing all the patients, patient locations, and the responsible attendings should be given personally to the cross-cover intern. Any investigations performed at night (e.g., lab studies, chest x-ray, electrocardiogram [ECG]) should be checked that night by the covering intern. No test order should go unchecked. Abnormal lab values should be reviewed and discussed with the senior resident or the attending staff, especially on preoperative patients. Starting antibiotics should be a decision left to the senior resident or attending staff. If consultants are asked to see patients, their recommendations mustbe discussed with your senior resident or attending priorto initiating any new plans. Independent thought is good; independent action is bad.

SUPERVISION

5. Document all procedures performed on patients—including arterial lines, chest tubes, and central lines—with a short procedure note in the chart. Every patient contact should be documented in the patient record.If you see a patient in the middle of the night, write a short note to describe your assessment and plan. Remember, if there is no documentation, then nobody responded to the patient’s complaint or needs. Obtain appropriate supervision for procedures. There are always more senior residents available if your chief is not. Protect yourself; practice universal precautions! Wash your hands before and after examining a patient. Wear gloves. All wounds should be inspected every day by the surgical intern as part of the clinical examination. Please re-dress them; the nursing staff is not always immediately available to do so. There should never be any surprises in the morning.

RESIDENTS

Your senior resident is responsible for the service and should be kept aware of any problems, regardless of the time of day. If the senior resident is not available, the attending staff should be contacted directly. There are always senior residents in the hospital who are available to be used as resources for emergencies. Always be aware of who is in-house (i.e., consult resident, ICU resident, trauma chief). A surgery resident’s days are long. They start early and they fi nish late. Always remember the three A’s to being a successful resident: Affable, Available, and Able. Be prepared to maintain a flexible daily schedule depending on the workload of the service and the requirement for additional manpower.

Leadership in SURGICAL TEAM

Leadership is a process of social influence in which one person can enlist the aid and support of others in the accomplishment of a common task. Successful leaders can predict the future and set the most suitable goals for organizations. Effective leadership among medical professionals is crucial for the efficient performance of a healthcare system. Recently, as a result of various events and reports such as the ‘Bristol Inquiry’, and ‘To Err is Human’ by the Institute of Medicine, the healthcare organizations across different regions have emphasized the need for effective leadership at all levels within clinical and academic fields. Traditionally, leadership in clinical disciplines needed to display excellence in three areas: patient care, research and education.

Within the field of surgery, the last decade has seen various transformations such as technology innovation, changes to training requirements, redistribution of working roles, multi-disciplinary collaboration and financial challenges. Therefore, the current concept of leadership demands to set up agendas in line with the changing healthcare scenario. This entails identifying the needs and initiating changes to allow substantive development and implementation of up-to-date evidence. This article delineates the definition and concept of leadership in surgery. We identify the leadership attributes of surgeons and consider leadership training and assessment. We also consider future challenges and recommendations for the role of leadership in surgery.

PRINCIPLES OF LEADERSHIP FOR GENERAL SURGEONS

VALORES ÉTICOS DOS ESTAGIÁRIOS DA CLÍNICA CIRÚRGICA

EXCELÊNCIA

Nunca baixar os seus padrões pessoais e profissionais. Fazer sempre o melhor, NÃO SOMENTE O POSSÍVEL.

Fazer sempre a coisa certa, mesmo quando ninguém está olhando.

RESPONSABILIDADE

Cumprir rigorosamente as atribuições em relação aos cuidados com os pacientes do serviço.

Ser uma força positiva com comprometimento na melhor assistência ao paciente.

DISCIPLINA

É a construção diária do seu objetivo.

O sucesso vem um pequeno passo de cada vez. O amanhã começa agora.

Turma 02 de RM Cirurgia Geral (HTLF)

Dr Antonio Filho (UEMA)

Dr Arimatéia Morales (UESPI)

Dra Livia Andrade (UFMA)

Dra Maura Calazeiras (UNICEUMA – APROVADA EM COLOPROCTOLOGIA NA UFCE)

Dr Igor Neiva (UNICEUMA – APROVADO EM ONCOLOGIA CIRÚRGICA NO INCA – RJ)

A todos os ex-residentes desejamos boa sorte e muitas realizações nesta nova etapa profissional.

Surgical Rotation: 5 PRINCIPLES

1.Getting along with the nurses.

The nurses do know more than the rest of us about the codes, routines, and rituals of making the wards run smoothly. They may not know as much about pheochromocytomas and intermediate filaments, but about the stuff that matters, they know a lot. Acknowledge that, and they will take you under their wings and teach you a ton!

2. Helping out.

If your residents look busy, they probably are. So, if you ask how you can help and they are too busy even to answer, asking again probably would not yield much. Always leap at the opportunity to shag x-rays, track down lab results, and retrieve a bag of blood from the bank. The team will recognize your enthusiasm and reward your contributions.

3. Getting scutted.

We all would like a secretary, but one is not going to be provided on this rotation. Your residents do a lot of their own scut work without you even knowing about it. So if you feel like scut work is beneath you, perhaps you should think about another profession.

4. Working hard.

This rotation is an apprenticeship. If you work hard, you will get a realistic idea of what it means to be a resident (and even a practicing doctor) in this specialty. (This has big advantages when you are selecting a type of internship. Staying in the loop. In the beginning, you may feel like you are not a real part of the team. If you are persistent and reliable, however, soon your residents will trust you with more important jobs. Educating yourself, and then educating your patients. Here is one of the rewarding places (as indicated in question 1) where you can soar to the top of the team. Talk to your patients about everything (including their disease and therapy), and they will love you for it.

5. Maintaining a positive attitude.

As a medical student, you may feel that you are not a crucial part of the team. Even if you are incredibly smart, you are unlikely to be making the crucial management decisions. So what does that leave: attitude. If you are enthusiastic and interested, your residents will enjoy having you around, and they will work to keep you involved and satisfied. A dazzlingly intelligent but morose complainer is better suited for a rotation in the morgue. Remember, your resident is likely following 15 sick patients, gets paid less than $2 an hour, and hasn’t slept more than 5 hours in the last 3 days. Simple things such as smiling and saying thank you (when someone teaches you) go an incredibly long way and are rewarded on all clinical rotations with experience and good grades.

Having fun! This is the most exciting, gratifying, rewarding, and fun profession and is light years better than whatever is second best (this is not just our opinion).

By: Alden H. Harken MDProfessor and Chair, Department of Surgery, University of California, San Francisco–East Bay, Oakland, California, Chief of Surgery, Department of Surgery, Alameda County Medical Center, Oakland, California

“poderosos além de qualquer medida…”

Nosso medo mais profundo não é o de sermos inadequados. Nosso medo mais profundo é que somos poderosos além de qualquer medida. É a nossa luz, não nossa escuridão, que mais nos assusta. Nós nos perguntamos: Quem sou eu para ser brilhante, maravilhoso, talentoso e fabuloso? Na verdade, quem não quer que você seja? Você é um filho de Deus. Seu papel pequeno não serve ao mundo. Não há nada de iluminado em se encolher, para que outras pessoas não se sintam inseguros ao seu redor. Estamos todos feitos para brilhar, como as crianças. Nascemos para manifestar a glória de Deus que está dentro de nós. Não é apenas em alguns de nós, está em todos. E conforme deixamos nossa própria luz brilhar, inconscientemente damos às outras pessoas permissão para fazer o mesmo. Como estamos libertamos do nosso medo, nossa presença, automaticamente, libera os outros.

Esse texto é atribuído a Marianne Williamson, uma autora e palestrante americana. A passagem faz parte de seu livro “A Return to Love: Reflections on the Principles of A Course in Miracles” (1992). Williamson explora temas de autoaceitação, potencial humano e espiritualidade, incentivando as pessoas a reconhecerem e expressarem sua luz interior. A citação destaca a ideia de que o verdadeiro medo não está em nossa inadequação, mas no poder e potencial que temos para impactar positivamente o mundo ao nosso redor.

World’s Greatest Surgeon

On July 12, 2008, the world lost an incredible talent. A renegade physician, a pioneer, the father of open-heart surgery, and perhaps the best surgeon who ever lived, Dr. Michael DeBakey died of natural causes at 99. Because of his groundbreaking research, cutting-edge medical devices and maverick approach to cardiac surgery, DeBakey literally changed the rules of the game and thousands of lives are saved each day.

On July 12, 2008, the world lost an incredible talent. A renegade physician, a pioneer, the father of open-heart surgery, and perhaps the best surgeon who ever lived, Dr. Michael DeBakey died of natural causes at 99. Because of his groundbreaking research, cutting-edge medical devices and maverick approach to cardiac surgery, DeBakey literally changed the rules of the game and thousands of lives are saved each day.

What can we learn from Michael DeBakey’s life and career?

1. Build your brand.

With a career that spanned more than 70 years, DeBakey built a reputation for being indispensable. His patients included everyone from the ordinary person next door and people with no means to a list of Who’s Who among world leaders. Presidents Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon, President Boris Yeltsin, King Hussein of Jordan, the Shah of Iran, Turkish President Turgut Ozal, just to name a few, engaged DeBakey because they knew he was the best. The Journal of the American Medical Association said in 2005, “Many consider Michael E. DeBakey to be the greatest surgeon ever.” Is your personal brand strong enough that if you left your company, colleagues and customers would have a difficult time getting along without you?

2. Be a guru, thought leader, industry expert.

Dr. DeBakey published more than 1,000 medical reports, research papers, chapters and books on topics related to cardiovascular medicine. He helped establish the National Library of Medicine, the world’s largest and most prestigious repository of medical archives. DeBakey played a key role in organizing a specialized medical center system to treat soldiers returning from the war. This system is now the Veterans’ Administration Medical Center System. For his numerous contributions Dr. DeBakey was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Congressional Gold Medal, Congress’ highest civilian honor, the National Medal of Science, the country’s highest scientific award, and The United Nations Lifetime Achievement Award. Do people see you as a guru in your field? How distinctive is your knowledge base? How well do you garner, contribute and leverage knowledge?

3. Never quit learning.

As a child, DeBakey was required to borrow a book from the library each week and read it. He read the entire Encyclopedia Britannica before entering high school. Overseeing cases, consulting with colleagues and mentoring younger surgeons, he made his mark on the world right up to the end. DeBakey performed his last surgery at age 90 and continued to travel the globe giving lectures. Perhaps you’re thinking, “Who would want a 90-year-old surgeon operating on them?” The answer could be, “Someone who’s performed more than 60,000 cardiovascular procedures in his career.” Do you have a reputation for lifelong learning, for continually adding value? When we stop bringing something new to the game, the game is over.

4. Risk more, gain more.

DeBakey took risks others weren’t willing to take to advance medicine. Tubing, clamps, pumps, protocols all bear the mark of DeBakey’s passion for innovation. Yet, product and process innovations often pull people out of their comfort zones and some of DeBakey’s early breakthroughs weren’t accepted initially—in fact they were ridiculed. For example, in 1939, when Drs. DeBakey and Alton Ochsner linked cigarette smoking to lung cancer, many in the medical community derided it. Then in 1964, the Surgeon General confirmed their findings and documented the cause and effect. There was also skepticism when DeBakey discovered that he could substitute parts of diseased arteries with synthetic (Dacron) grafts—a procedure that enables surgeons to repair aortic aneurysms in the chest and abdomen. He initially figured out how to stitch synthetic blood vessels on his wife’s sewing machine. Now the procedure is widely used. DeBakey was also the first to perform bypass surgery and the first to perform a successful removal of a blockage of the carotid (main) artery of the neck, a procedure that has become the standard protocol for treating stroke. The world is not changed by those who are unwilling to take risks. Is your passion for advancing your field by taking a risk bigger than your fear of rejection or making a mistake?

5. Refuse to sell out on your dream.

DeBakey developed an interest in medicine in his father’s pharmacy where he listened to physicians talk shop. The vision to become a doctor was clear, the question was, “what kind?” In 1932, there simply wasn’t anything you could do for heart disease, if a patient had a heart attack the long-term prognosis wasn’t good. While he was still in school in 1932, DeBakey invented the roller pump—a critical part of the heart-lung machine that takes over the functions of the heart and lungs during open-heart surgery. This not only created the era of open-heart surgery, it cemented DeBakey’s passion to make a mark in the world of cardiovascular medicine. Engagement is about pouring your heart, mind and soul into a dream that causes you to fire on all cylinders. Does your career fulfill your desires? Or, have you sacrificed a dream that could make you come alive for a life of duty and routine that simply “works”?

6. Play to your genius.

DeBakey said, “I like my work, very much. I like it so much that I don’t want to do anything else.” Most people who are happy in life spend time doing what they love. This usually makes them extremely good at what they do. Dr. DeBakey exemplified the power of what can happen when our work requires what we are good at and passionate about. Playing to your genius is about using your gifts and talents to pursue a passion that makes a significant contribution to the people and the world you serve. Playing to your genius also promotes autonomy and self-direction, cultivates commitment, stimulates personal growth and makes work fun. Are you engaged in work you’re good at and passionate about—work that makes a contribution and needs to be done? Or are you just biding time?

7. Balance passion with discipline and focus.

With regard to his patients, the indefatigable DeBakey had an uncompromising dedication to perfection. He was known as a taskmaster who set very high standards, yet he never demanded more from others than he demanded from himself. Heart surgeons who trained under DeBakey say he was hard to keep up with when making patient rounds. They joked that he was from another world because he could maintain his focus and intensity for hours. In a world of competing priorities and information overload it’s easy to lose focus and get distracted. But, if you are playing to your genius and doing what you love, it’s easier to be disciplined and maintain a maniacal focus. Are you disciplined? Do you have a maniacal focus? Would your customers (internal and external) say you are relentless when it comes to pursuing perfection?

8. Find a void and figure out how to fill it.

Michael DeBakey’s innovations are on par with the likes of Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, Jonas Salk, Henry Ford and Alfred Nobel. During World War II, he helped establish the mobile army surgical hospitals or MASH units. He was a key player in the development of artificial hearts, artificial arteries and bypass pumps that help keep patients alive who are waiting for transplants. He was among the first to recognize the importance of blood banks and transfusions. He also helped create more than 70 surgical instruments that made procedures easier and clinical outcomes more effective. If something couldn’t be done, DeBakey found a way to do it. In 1967, Dr. Christiaan Barnard performed the first human heart transplant in South Africa. Dr. DeBakey was among the first to begin doing the procedure in the United States. The problem was that recipients’ bodies rejected the new organs and death rates were high. In the 1980s cyclosporine, a new anti-rejection drug paved the way for organ transplants. Again, DeBakey was among the first to develop new protocols and advance the field of heart transplants. Where are the gaps in your organization or industry? What would happen if you developed a reputation for filling these voids?

9. Show people that their work matters.

Michael DeBakey is known not only for his prolific contributions to the medical field, but also as a symbol of hope and encouragement to his colleagues. Many years ago a colleague of ours shadowed Dr. DeBakey for a day at The Methodist Hospital in Houston, Texas. He was struck by DeBakey’s capacity to affirm each person he saw in the course of the day. In one particular encounter, DeBakey began chatting with an elderly janitor who was sweeping the floor. DeBakey asked the man about his wife and children. He told the older man, obviously not for the first time, that the hospital couldn’t function without the janitor because germs would spread, increasing the chances of infection in the hospital. Later in the day, our colleague tracked down the janitor and asked him, “What exactly do you do? Tell me about your job.” With pride, the janitor replied: “Dr. DeBakey and I? We save lives together.” He’s right. After all, consider what would happen to our healthcare systems if the cleaning crews went on strike. DeBakey understood that showing the janitor exactly how he contributes to a larger, more heroic cause is crucial. This creates a powerful dynamic. Realizing that he is working toward a worthy goal, the janitor’s perceptions about his work changed. It had new meaning and his enthusiasm for the job was rejuvenated. Great leaders make time to help people see how their work is connected to something bigger. For a surgeon like DeBakey, those five or ten minutes each day were costly, unless, of course, you consider the productivity generated by a janitor whose work has been transformed. Right now, how many people in your organization are engaged in work that five years from today no one will give a rip about? Can you make the link between what you do and a noble or heroic cause? Can you make this link for others?

10. Be generative—inspire others to pursue the cause.

Generativity is the care and concern for the development of future generations through teaching, mentoring, and other creative contributions. It’s about leaving a positive legacy. All great leaders are generative and Michael DeBakey was no exception. He inspired many medical students to pursue careers in cardiovascular surgery. His reputation brought many people to Baylor College of Medicine and helped transform it into one of the premier medical institutions in the world. DeBakey trained and mentored almost 1,000 surgeons and physicians. In 1976, his students founded the Michael E. DeBakey International Surgical Society. Many of his residents went on to serve as chairpersons and directors of their own successful academic surgical programs in the United States and around the world. Are the people you’ve touched in your career learning, growing and making a difference as a result of your influence? Have they been inspired to build a better world than the world they inherited? Michael DeBakey applied his problem-solving skills to many parts of medicine that have changed our way of life. Timothy Gardner, M.D., president of the American Heart Association said it well, “DeBakey’s legacy will live on in so many ways—through the thousands of patients he treated directly and through his creation of a generation of physician educators, who will carry his legacy far into the future. His advances will continue to be the building blocks for new treatments and surgical procedures for years to come.”

Michael DeBakey’s life and legacy proves that one person who chooses to play to their genius can change the world and make it a better place for all. What legacy will you leave behind?

O CIRURGIÃO (POEMA)

O CIRURGIÃO

Um corpo inerte aguarda sobre a mesa

Naquele palco despido de alegria.

O artista das obras efêmeras se apresenta.

A opereta começa, ausente de melodia

E o mascarado mudo trabalha com presteza.

Sempre começa com esperança e só términa com certeza.

Se uma vida prolonga, a outra vai-se escapando.

E nem sempre do mundo o aplauso conquistando

Assim segue o artista da obra traiçoeira e conquistas passageiras.

Há muito não espera do mundo os louros da vitória

Estudar, trabalhar é sua história, e a tua maior glória

Hás de encontrar na paz do dever cumprido.

Quando a vivência teus cabelos prateando

E o teu sábio bisturi, num canto repousando

Uma vez que sua missão vai terminando

Espera do bom Deus por tudo, a ti, seja piedoso.

SOIS VÓS INSTRUMENTO DA TUA OBRA.

.

Qual o momento certo? AGORA.

“So live your life that the fear of death can never enter your heart. Trouble no one about their religion; respect others in their view, and demand that they respect yours. Love your life, perfect your life, beautify all things in your life. Seek to make your life long and its purpose in the service of your people. Prepare a noble death song for the day when you go over the great divide. Always give a word or a sign of salute when meeting or passing a friend, even a stranger, when in a lonely place. Show respect to all people and grovel to none. When you arise in the morning give thanks for the food and for the joy of living. If you see no reason for giving thanks, the fault lies only in yourself. Abuse no one and no thing, for abuse turns the wise ones to fools and robs the spirit of its vision. When it comes your time to die, be not like those whose hearts are filled with the fear of death, so that when their time comes they weep and pray for a little more time to live their lives over again in a different way. Sing your death song and die like a hero going home.”

~ Chief Tecumseh (Poem from Act of Valor the Movie)

The Qualities of a GOOD SURGEON

Following is a list of Dr. Ephraim McDowell’s personal qualities described as “C” words along with evidence corroborating each of the characteristics.

Courageous: When he agreed to attempt an operation that his teachers had stated was doomed to result in death, he, as well as his patient, showed great courage.

Compassionate: He was concerned for his patient and responded to Mrs. Crawford’s pleas for help.

Communicative: He explained to his patient the details of her condition and her chances of survival so that she could make an informed choice.

Committed: He promised his patient that if she traveled to Danville, he would do the operation. He made a commitment to her care.

Confident: He assured the patient that he would do his best, and she expressed confidence in him by traveling 60 miles by horseback to his home.

Competent: Although lacking a formal medical degree, he had served an apprenticeship in medicine for 2 years in Staunton, Virginia, and he had spent 2 years in the study of medicine at the University of Edinburgh, an excellent medical school. In addition, he had taken private lessons from John Bell, one of the best surgeons in Europe. By 1809 he was an experienced surgeon.

Carefull: Despite the fact that 2 physicians had pronounced Mrs. Crawford as pregnant, he did a careful physical examination and diagnosed that she was not pregnant but had an ovarian tumor. He also carefully planned each operative procedure with a review of the pertinent anatomic details. As a devout Presbyterian, he wrote special prayers for especially difficult cases and performed many of these operations on Sundays.

Courteous: He was humble and courteous in his dealings with others. Even when he was publicly and privately criticized after the publication of his case reports, he did not react with vitriol. The qualities of character demonstrated by Dr. Ephraim McDowell 200 years ago are still essential for surgeons today.

Dr. Ephraim McDowell exemplified the essential qualities that define a great surgeon. His courage was evident when he accepted to perform an operation deemed fatal by his mentors, facing the unknown with determination. His compassion shone through in his genuine concern for the well-being of his patients, responding to cries for help with sensitivity and empathy. He was communicative, ensuring that his patients were well-informed about their conditions and the risks involved, enabling decisions based on knowledge. Additionally, Dr. McDowell demonstrated unwavering commitment to his patients, keeping promises and ensuring that each received the best possible care.

His confidence in his abilities, even without a formal degree, was supported by a robust education and a continuous dedication to learning. Dr. McDowell was competent, the result of years of study and practice, conducting meticulous physical examinations and planning each procedure with precision. His courtesy and humility in interactions, even in the face of criticism, showed a character that valued respect and integrity. These qualities, demonstrated two centuries ago, are timeless and continue to define ethical practice in modern surgery. As William Osler aptly stated, “The practice of medicine is an art, not a trade; a calling, not a business; a calling in which your heart will be exercised equally with your head.”

Etiqueta Médica : Postura Cirúrgica na U.T.I.

A etiqueta no ambiente hospitalar vai além das regras de boa convivência. Ela oferece recursos para que os profissionais construam relacionamentos sólidos, além de ensiná-los a lidar com os “sabotadores da carreira”, como indiscrição e a falta de educação. Logo as atitudes no trabalho devem ser pautadas pelo bom senso, pelo bom gosto e pelo equilíbrio. Esses três fatores têm um único objetivo: fazer-nos pessoas melhores na convivência com os demais. Certamente, pensar muito antes de agir nos protege de escolhas equivocadas de comportamentos. As relações de trabalho e os ambientes hospitalares mudaram muito nos últimos anos, assim como as regras de convivência e as competências relacionais. Hoje, muitas empresas adotam estações de trabalho em que todos compartilham o mesmo espaço. Tudo o que se fala pode ser ouvido. A privacidade é muito menor, o que exige discrição. As atribuições das lideranças também evoluíram: em vez de mandar, os líderes devem convencer as suas equipes para serem respeitados. Outro desafio é promover a boa convivência entre gerações diferentes nas empresas. Os avanços tecnológicos exigem muito mais dos relacionamentos com colegas de todos os níveis. Portanto, o uso de emails, redes sociais e mensagens instantâneas, entre outros recursos, deve preservar sempre a cortesia, o respeito e a devida atenção ao outro. Sendo a “regra de platina” das relações humanas: trate os outros melhor do que você gostaria de ser tratado!

A etiqueta no ambiente hospitalar vai além das regras de boa convivência. Ela oferece recursos para que os profissionais construam relacionamentos sólidos, além de ensiná-los a lidar com os “sabotadores da carreira”, como indiscrição e a falta de educação. Logo as atitudes no trabalho devem ser pautadas pelo bom senso, pelo bom gosto e pelo equilíbrio. Esses três fatores têm um único objetivo: fazer-nos pessoas melhores na convivência com os demais. Certamente, pensar muito antes de agir nos protege de escolhas equivocadas de comportamentos. As relações de trabalho e os ambientes hospitalares mudaram muito nos últimos anos, assim como as regras de convivência e as competências relacionais. Hoje, muitas empresas adotam estações de trabalho em que todos compartilham o mesmo espaço. Tudo o que se fala pode ser ouvido. A privacidade é muito menor, o que exige discrição. As atribuições das lideranças também evoluíram: em vez de mandar, os líderes devem convencer as suas equipes para serem respeitados. Outro desafio é promover a boa convivência entre gerações diferentes nas empresas. Os avanços tecnológicos exigem muito mais dos relacionamentos com colegas de todos os níveis. Portanto, o uso de emails, redes sociais e mensagens instantâneas, entre outros recursos, deve preservar sempre a cortesia, o respeito e a devida atenção ao outro. Sendo a “regra de platina” das relações humanas: trate os outros melhor do que você gostaria de ser tratado!

Ao encaminhar o paciente no pós-operatório para U.T.I. o Cirurgião legalmente mantém sua responsabilidade sob os cuidados cirúrgicos deste paciente, sendo a partir daí um dos profissionais que participará na orientação das condutas clínicas relacionadas ao procedimento cirúrgico do paciente. Desta forma deve ficar á livre disposição dos INTENSIVISTAS para dirimir qualquer dúvida ou prestar orientações quanto a evolução cirúrgica do paciente em questão.

Alguns cuidados são importantes para serem lembrados nesta relação CIRURGIÃO e o Corpo Clínico das Unidades de TERAPIA INTENSIVA…

- Ao executar um procedimento cirúrgico, lembre-se que se algum evento adverso pode ocorrer, este um dia irá acontecer (Lei de Murphy). Prepara-se o pior possível. Se pensas que após uma complicação cirúrgica as coisas não podem piorar, acredite que podem. E serão justamente esta equipe de Especialistas que nos ajudaram a conduzir melhor o caso.

- Nada na Medicina permanece constante, em especial no pós-operatório, e nenhum órgão falha isoladamente.

- Cuidado com a Lei da Especialização: se fores um martelo, o resto do mundo é um prego. Aquele que pensa que sabe tudo, não sabe nada.

- Um “abdómen agudo cirúrgico” é diagnosticado após o exame físico por parte de um cirurgião EXPERIENTE e COMPROMETIDO, podendo ou não ser ratificado pelos exames complementares. Não existe nenhum teste complementar isolado para isso.

- Antes de solicitarmos um exame complementar, precisamos planejar o que faremos se for positivo ou negativo. Se as respostas forem iguais, não o solicitaremos. Corolário: Se o teste não altera a nossa estratégia, não solicitaremos.

- Não existe nenhum efeito adverso que não possa ser causado por um determinado fármaco. Se o fármaco não é essencial no tratamento, não usaremos.

- Geralmente a qualidade do cuidado prestado ao paciente é inversamente proporcional ao número de especialidades (consultores) envolvidos nesse caso particular. Todo paciente cirúrgico possui um único cirurgião responsável pelo procedimento em questão.

- Se as orientações médicas forem passíveis de má interpretação pela equipe multidisciplinar, elas certamente serão mal interpretadas. Portanto precisamos sempre nos perguntar: “Eu fui claro nas minhas orientações?”.

- Nunca ignore uma chamada de atenção de um dos membros da equipe Multidisciplinar, em especial do corpo de enfermagem. É função destes colegas nos informar. A nossa função é decidir. Seja cordial e serás retribuído da mesma maneira. Se fores desagradável, terás uma vida miserável. Jamais confunda o carteiro com a mensagem da carta.

- Se não sabes o que fazer, não faças nada e pede ajuda. Fazer mal não é melhor que não fazer nada. Pede e insiste na ajuda se tiveres dúvidas ou complicações que você nunca conduziu. Erros de inexperiência em doentes críticos podem ter consequências catastróficas.

Deixe nos comentários a sua contribuição.

BOM PLANTÃO.

Prof. Dr. Henrique Walter Pinotti (Gastrão 2009)

“A cirurgia lida com a VIDA, logo não existe cirurgia banal.”

A cirurgia do aparelho digestivo deve ser conceituada como ciência e arte que, através do progresso técnico e da melhor organização das sociedades, expandiu seus horizontes. Hoje, essa especialidade médica se aproxima cada vez mais do indivíduo, compreendendo suas enfermidades, emoções e função na sociedade. Ao cirurgião digestivo, protagonista dessa especialidade, cabe o papel não só de tratar eficientemente, mas também de conhecer as causas das doenças e criar atitudes preventivas. Além disso, deve considerar os ônus sociais e econômicos das enfermidades cirúrgicas e adotar uma visão bio-psico-social do paciente.

O fundamento Filosófico da Cirurgia Digestiva

Hipócrates, o Pai da Medicina, já havia estabelecido os elos entre medicina e filosofia. Ele afirmava: “O médico que é, ao mesmo tempo, filósofo assemelha-se aos deuses. Não há grande diferença entre a medicina e a filosofia, porque todas as qualidades do bom filósofo devem ser encontradas no médico: desinteresse, zelo, pudor, dignidade, seriedade, tranquilidade de julgamento, serenidade, decisão, pureza de vida, conhecimento do que é útil e necessário na vida, reprovação do que é mau, alma livre de suspeitas e devoção à divindade.” Claudius Galenus, conhecido como Galeno, complementou essa visão com sua vasta produção literária, afirmando que “o ótimo médico necessita ser também ótimo filósofo”. Para ele, a prática da medicina exigia um profundo conhecimento filosófico.

A Filosofia da Cirurgia

A filosofia como ciência lida com o saber racional, sendo uma reflexão crítica sobre os fundamentos do conhecimento e seus valores normativos: lógica, ética e estética. A Filosofia da Cirurgia é uma ciência cujos conhecimentos e objetivos transcendem os de outras filosofias, pois lida diretamente com a vida humana e toda a complexidade que sua prática requer. Conduzida sob o signo da ética, visa gerar felicidade para o operado e seus dependentes. Essa filosofia é robustecida tanto na direção individual quanto na missão social, especialmente quando o profissional possui grande sensibilidade humana e uma ampla formação técnica e ética. Enquanto no Direito existe o princípio de “tratar de maneira distinta os desiguais”, a Cirurgia, embora recomende procedimentos diferentes conforme a doença e o estado do paciente, trata igualmente os socialmente desiguais. Na doença, todos são iguais; o paciente anestesiado pertence ao mundo dos iguais.

Doutrina Filosófica da Cirurgia Digestiva

A doutrina da Filosofia da Cirurgia tem finalidades elevadas, superando as de muitas outras profissões, pois coloca as necessidades do paciente acima dos interesses pessoais. A prática cirúrgica, conduzida com ética e conhecimento profundo, busca não apenas a cura, mas o bem-estar e a felicidade do paciente e de seus familiares. A cirurgia é uma especialidade médica dedicada ao tratamento de doenças, traumas e complicações de saúde por meio de intervenções manuais e instrumentais realizadas por médicos especializados. No contexto da cirurgia digestiva, essas intervenções são focadas no sistema digestivo, englobando uma série de órgãos essenciais para a digestão, absorção de nutrientes e eliminação de resíduos do corpo.

O Sistema Digestivo e Suas Funções

O sistema digestivo começa na boca e se estende até o ânus, incluindo órgãos como intestino grosso e delgado, estômago, duodeno, faringe e fígado. Esses órgãos são responsáveis não apenas pela digestão dos alimentos, mas também pela absorção de nutrientes e eliminação de substâncias desnecessárias ao organismo. Todo o processo digestivo é regulado pelo sistema nervoso e por hormônios, com o cérebro desempenhando um papel crucial na percepção da fome e no início da digestão.

A Importância de Escolher um Especialista em Cirurgia do Aparelho Digestivo

Qualquer procedimento cirúrgico é delicado, exigindo uma combinação de conhecimentos técnicos, éticos e humanísticos. No campo da cirurgia do aparelho digestivo, essa responsabilidade é ainda maior devido à complexidade das doenças tratadas e à precisão exigida nas intervenções. Portanto, é fundamental que o cirurgião responsável tenha a formação e a experiência necessárias para oferecer o melhor cuidado possível aos pacientes.

Formação e Qualificação do Cirurgião do Aparelho Digestivo

Um cirurgião do aparelho digestivo é um profissional altamente capacitado, com pelo menos 10 anos de estudos obrigatórios, que envolvem:

- 6 anos de graduação em Medicina;

- 2 anos de Residência Médica em Cirurgia Geral;

- 2 anos de Residência Médica em Cirurgia do Aparelho Digestivo, regulamentada pelo Ministério da Educação (MEC) e pelo Conselho Federal de Medicina (CFM).

Esse período de treinamento permite ao cirurgião não apenas adquirir o conhecimento teórico, mas também desenvolver as habilidades práticas necessárias para realizar procedimentos complexos com segurança e eficiência. Além disso, o cirurgião do aparelho digestivo está habilitado a utilizar tanto técnicas convencionais quanto métodos minimamente invasivos, como a cirurgia laparoscópica e endoscopia diagnóstica, que resultam em menor tempo de recuperação e menos dor para o paciente.

Áreas de Atuação e Doenças Tratadas

Os cirurgiões do aparelho digestivo são especializados em diagnosticar, tratar e prevenir uma ampla gama de doenças que afetam os órgãos abdominais. Entre os principais tratamentos realizados por esses especialistas estão as cirurgias de câncer do estômago, esôfago, intestinos, reto, pâncreas, fígado, vesícula biliar e vias biliares. Esses profissionais não apenas realizam os procedimentos cirúrgicos para tratar esses tipos de câncer, mas também atuam na prevenção, oferecendo aconselhamento e exames regulares aos pacientes em risco.

Além disso, o cirurgião do aparelho digestivo trata diversas outras condições comuns, como:

- Refluxo gastroesofágico e esofagite;

- Hérnia de hiato e da parede abdominal;

- Obesidade mórbida (cirurgia bariátrica);

- Gastrite e úlcera gástrica/duodenal;

- Tumores malignos do aparelho digestivo;

- Transplante de Órgãos do Aparelho Digestivo;

- Pancreatite e cálculos biliares;

- Doença diverticular (diverticulite);

- Retocolite ulcerativa e doença de Crohn;

- Hemorróidas, fístulas e fissuras anais;

- Hérnias da parede abdominal, entre outras condições.

Escolhendo o Cirurgião

Antes de se submeter a qualquer procedimento cirúrgico, é crucial que o paciente verifique a formação e as qualificações do médico responsável. Aqui estão alguns pontos importantes a serem considerados:

- Formação Acadêmica: Certifique-se de que o médico possui os requisitos de formação necessários, incluindo residência em cirurgia do aparelho digestivo.

- Afiliado a Entidades Científicas: Verifique se o cirurgião é membro de alguma sociedade científica representativa, como o Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgia Digestiva (CBCD) ou a Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Bariátrica e Metabólica (SBCBM).

- Atualização Constante: O campo da medicina está sempre evoluindo, e é essencial que o cirurgião mantenha-se atualizado com os últimos avanços em sua área.