10 Anatomical Aspects for Prevention the Bile Duct Injury

Essential aspects to visualize and interpret the anatomy during a cholecystectomy:

1. Have the necessary instruments for the procedure, with adequate positioning of the trocars and a 30-degree optic.

2. Cephalic traction of the gallbladder fundus and lateral traction (pointing to the patient’s right shoulder), to reduce redundancy of the infundibulum.

3. Puncture and evacuation of the gallbladder to improve its retraction, in cases where traction cannot be performed easily (acute cholecystitis).

4. Lateral and caudal traction of the infundibulum, for correct exposure of Calot’s triangle, exposing the CD and artery.

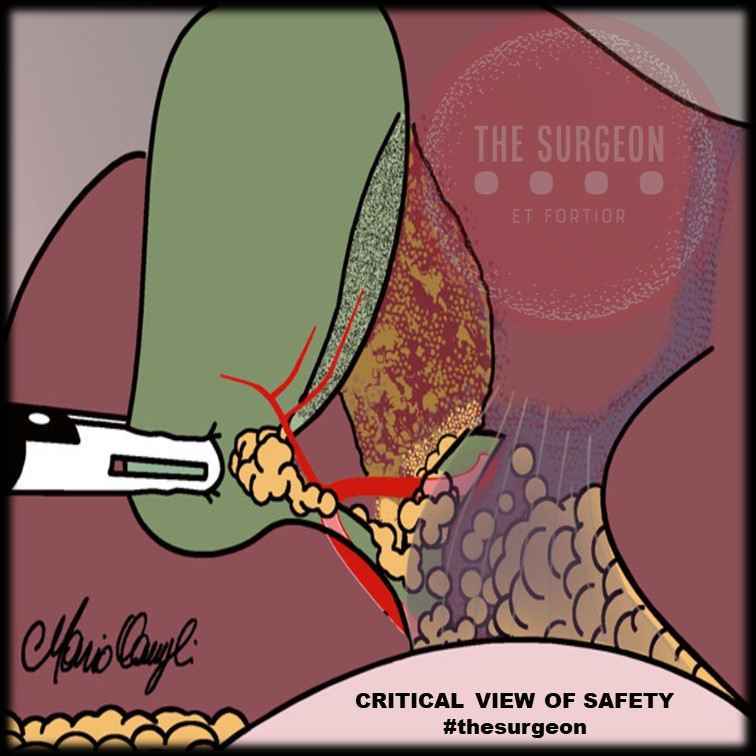

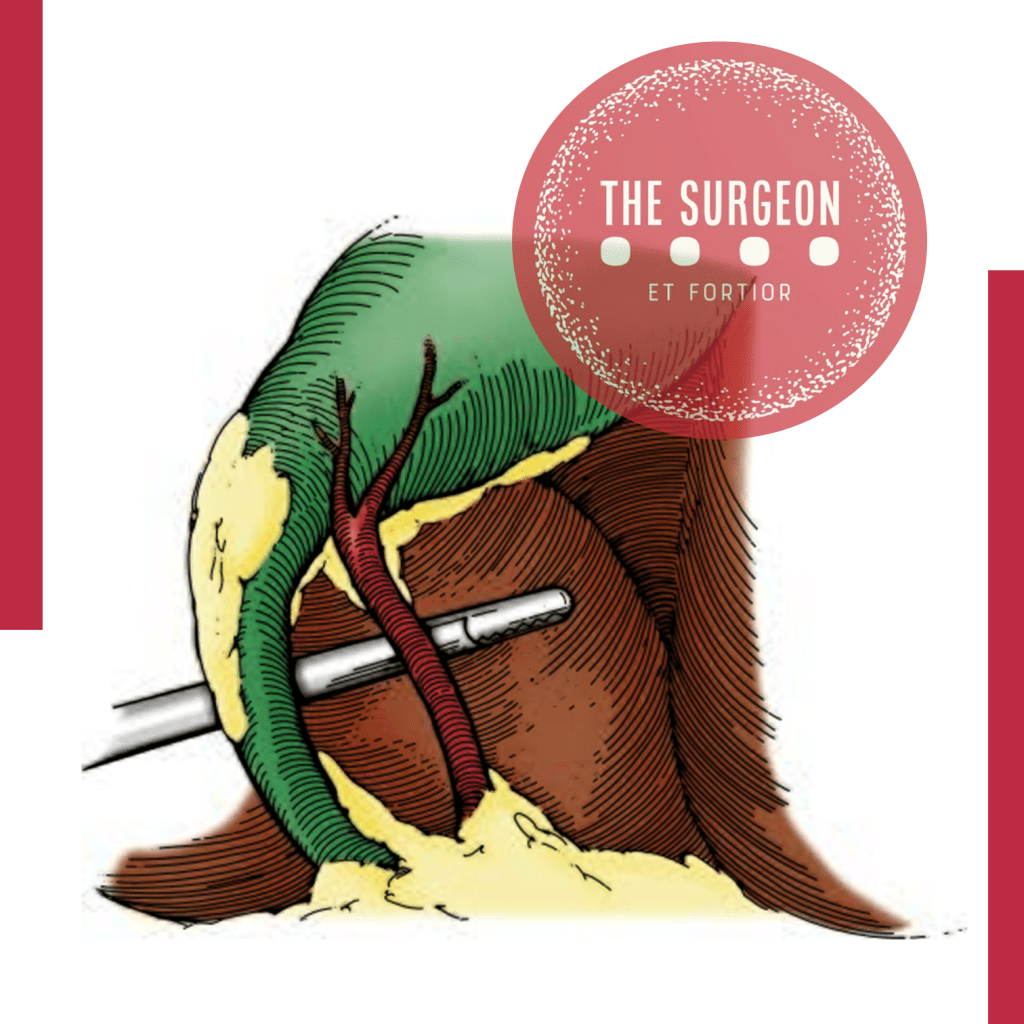

5. “Critical view of Safety” to avoid misidentification of the bile ducts, ensuring that only two structures (CD and artery) are attached to the gallbladder. For this, they must be dissected separately, and the proximal third of the gallbladder must be moved from its fossa, to ensure that there is no anatomical variant there.

6. Systematic use of intraoperative cholangiography. Ideally by transcystic route or possibly by a puncture of the gallbladder.

7. Ligation of the cystic duct with knots (“endoloop”) to prevent migration of metallic clips that could condition a postoperative leak.

8. In case of severe inflammation of the gallbladder pedicle, with its retraction or lack of recognition of cystic structures, a subtotal cholecystectomy might be indicated.

9. In case of hemorrhage, avoid indiscriminate clip placement and or blind cautery. Opt for compressive maneuvers and, once the bleeding site has been identified, evaluate the best method of hemostasis.

10. If the surgeon is not able to resolve the injury caused, it is always better to ask for help from a colleague, and if necessary, to refer the patient to a specialized center.

#SafetyFirst

The main goal in the postoperative management of BDI is to control sepsis in the first instance and to convert an uncontrolled biliary leak into a controlled external biliary fistula to achieve optimal local and systemic control. Definitive treatment to re-establish biliary continuity will be deferred once this primary goal is achieved and should not be obsessively pursued in the acute phase. The factors that will determine the initial presentation of a patient with a BDI in the postoperative stage are related to the time elapsed since the primary surgery, the type of injury, the mechanism of injury, and the overall general condition of the patient.

Critical View Of Safety

“The concept of the critical view was described in 1992 but the term CVS was introduced in 1995 in an analytical review of the emerging problem of biliary injury in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. CVS was conceived not as a way to do laparoscopic cholecystectomy but as a way to avoid biliary injury. To achieve this, what was needed was a secure method of identifying the two tubular structures that are divided in a cholecystectomy, i.e., the cystic duct and the cystic artery. CVS is an adoption of a technique of secure identification in open cholecystectomy in which both cystic structures are putatively identified after which the gallbladder is taken off the cystic plate so that it is hanging free and just attached by the two cystic structures. In laparoscopic surgery complete separation of the body of the gallbladder from the cystic plate makes clipping of the cystic structures difficult so for laparoscopy the requirement was that only the lower part of the gallbladder (about one-third) had to be separated from the cystic plate. The other two requirements are that the hepatocystic triangle is cleared of fat and fibrous tissue and that there are two and only two structures attached to the gallbladder and the latter requirements were the same as in the open technique. Not until all three elements of CVS are attained may the cystic structures be clipped and divided. Intraoperatively CVS should be confirmed in a “time-out” in which the 3 elements of CVS are demonstrated. Note again that CVS is not a method of dissection but a method of target identification akin to concepts used in safe hunting procedures. Several years after the CVS was introduced there did not seem to be a lessening of biliary injuries.

Operative notes of biliary injuries were collected and studied in an attempt to determine if CVS was failing to prevent injury. We found that the method of target identification that was failing was not CVS but the infundibular technique in which the cystic duct is identified by exposing the funnel shape where the infundibulum of the gallbladder joins the cystic duct. This seemed to occur most frequently under conditions of severe acute or chronic inflammation. Inflammatory fusion and contraction may cause juxtaposition or adherence of the common hepatic duct to the side of the gallbladder. When the infundibular technique of identification is used under these conditions a compelling visual deception that the common bile duct is the cystic duct may occur. CVS is much less susceptible to this deception because more exposure is needed to achieve CVS, and either the CVS is attained, by which time the anatomic situation is clarified, or operative conditions prevent attainment of CVS and one of several important “bail-out” strategies is used thus avoiding bile duct injury.

CVS must be considered as part of an overall schema of a culture of safety in cholecystectomy. When CVS cannot be attained there are several bailout strategies such a cholecystostomy or in the case of very severe inflammation discontinuation of the procedure and referral to a tertiary center for care. The most satisfactory bailout procedure is subtotal cholecystectomy of which there are two kinds. Subtotal fenestrating cholecystectomy removes the free wall of the gallbladder and ablates the mucosa but does not close the gallbladder remnant. Subtotal reconstituting cholecystectomy closes the gallbladder making a new smaller gallbladder. Such a gallbladder remnant is undesirable since it may become the site of new gallstone formation and recurrent symptoms . Both types may be done laparoscopically.”

Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg 1995;180:101-25.