Enhanced Recovery After Liver Surgery

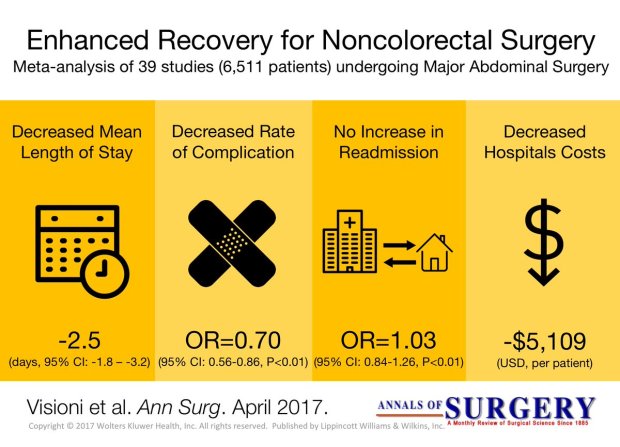

The first postoperative fast-track protocols, also called “enhanced recovery after surgery” (ERAS), were instituted by colorectal surgeons almost three decades ago in order to modulate surgical stress and hasten recovery. Since then, the implementation of enhanced recovery programs has had an exponential expansion across most surgical specialties, including gynecology, urology, breast, vascular, and orthopedic surgery.

“Enhanced recovery after liver surgery” (ERLS) was first introduced in 2008 and has incrementally gained acceptance as being an integral part of perioperative care for hepatectomy patients. Several outcome metrics have shown to be improved with the adoption of a multimodal evidencebased strategy in liver surgery, many of which are also shared by other surgical specialties practicing in an enhanced recovery framework.

Improved clinical outcomes such as length of stay, morbidity rates, and hospital costs tend to support implementation of fast-track programs in general, but other metrics specific to liver surgery and to patients with colorectal liver metastases (CLM) further endorse this strategy when managing CLM. The implementation of an ERLS program represents a collaborative approach in which the different team players, including anesthesia, surgery, nutrition, pharmacy, nursing, and most importantly the patient and his/her family, engage actively in the perioperative pathway, in an evidence-based, patient-centered approach. The development of such programs also requires dedicated continuing education for the team members, flexibility in terms of perioperative management and decisionmaking by the health-care providers, support from the hospital administration, and systematic quality control measures to ensure implementation and accurate reporting. This review study the different core elements of ERLS and discuss different outcomes associated with this system-based approach, with an emphasis on oncological patients.

Interference with oncological treatment plans can negatively affect patients’ longterm outcomes but can also be detrimental to quality of life and overall functional status. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) attempt to capture the patients’ perspective for a given intervention or treatment strategy, which are particularly important in oncological patients. Day et al. reported that the implementation of ERLS was beneficial for patients in terms of functional recovery, and although no significant differences were detected in terms of symptom burden, the impact of ERLS was shown to accelerate functional recovery by returning to baseline interference earlier. This positive effect from ERLS seems more pronounced in patients undergoing open hepatectomy over those already benefiting from minimally invasive surgery.

Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Over 50% to 60% of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer will develop hepatic metastases during their lifetime. Resection for hepatic metastases has been a routine part of treatment for colorectal cancer since the publication of a large single-center experience demonstrating its safety and efficacy.

Predictors of poor outcome in that study included node-positive primary, disease-free interval <12 months, more than one tumor, tumor size >5 cm, and carcinoembryonic antigen level >200 ng/mL.

Traditional teaching suggested that hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer to the liver, if technically feasible,should be performed only for fewer than four metastases. However, later studies challenged this paradigm. In a series of 235 patients who underwent hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer, the 10-year survival rate of patients with four or more nodules was 29%, nearly comparable to the 32% survival rate of patients with only a solitary tumor metastasis.

In the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center series of 98 patients with four or more colorectal hepatic metastases who underwent resection between 1998 and 2002, the 5-year actuarial survival was 33%. Furthermore, improved chemotherapeutic regimens and surgical techniques have produced aggressive strategies for the management of this disease.

Many groups now consider volume of future liver remnant and the health of the background liver, and not actual tumor number, as the primary determinants in selection for an operative approach. Hence, resectability is no longer defined by what is actually removed, but indications for hepatic resection now center on what will remain after resection.

Use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, portal vein embolization, twostage hepatectomy, simultaneous ablation, and resection of extrahepatic tumor in select patients have increased the number of patients eligible for a surgical approach.

Ischaemic Preconditioning applied to LIVER SURGERY

- INTRODUCTION

The absence of oxygen and nutrients during ischaemia affects all tissues with aerobic metabolism. Ischaemia of these tissues creates a condition which upon the restoration of circulation results in further inflammation and oxidative damage (reperfusion injury). Restoration of blood flow to an ischaemic organ is essential to prevent irreversible tissue injury, however reperfusion of the organ or tissues may result in a local and systemic inflammatory response augmenting tissue injury in excess of that produced by ischaemia alone. This process of organ damage with ischaemia being exacerbated by reperfusion is called ischaemia-reperfusion (IR). Regardless of the disease process, severity of IR injury depends on the length of ischaemic time as well as size and pre-ischaemic condition of the affected tissue. The liver is the largest solid organ in the body, hence liver IR injury can have profound local and systemic consequences, particularly in those with pre-existing liver disease. Liver IR injury is common following liver surgery and transplantation and remains the main cause of morbidity and mortality.

2. AETIOLOGY

The liver has a dual blood supply from the hepatic artery (20%) and the portal vein (80%). A temporary reduction in blood supply to the liver causes IR injury. This can be due to a systemic reduction or local cessation and restoration of blood flow. Liver resections are performed for primary or secondary tumours of the liver and carry a substantial risk of bleeding especially in patients with chronic liver disease. Significant blood loss is associated with increased transfusion requirements, tumour recurrence, complications and increased morbidity and mortality. Several methods of hepatic vascular control have been described in order to minimise blood loss during elective liver resection. The simplest and most common method is inflow occlusion by applying a tape or vascular clamp across the hepatoduodenal ligament (Pringle Manoeuvre). This occludes both the arterial and portal vein inflow to the liver and leads to a period of warm ischaemia (37 °C) to the liver parenchyma resulting in ‘warm’ IR injury when the temporary inflow occlusion is relieved. In major liver surgery, extensive mobilisation of the liver itself without inflow occlusion results in a significant reduction in hepatic oxygenation.

3. PATOPHYSIOLOGY and RISK FACTORS

A complex cellular and molecular network of hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC), leukocytes and cytokines play a role in the pathogenesis of IR injury. In general, both warm and cold ischaemia share similar mechanisms of injury. Hepatocyte injury is a predominant feature of warm ischaemia, whilst endothelial cells are more susceptible to cold ischaemic injury. There are currently no proven treatments for liver IR injury. Understanding this complex network is essential in developing therapeutic strategies in prevention and treatment of IR injury. Identifying risk factors for IR injury are extremely important in patient selection for liver surgery and transplantation. The main factors are the donor or patient age, the duration of organ ischaemia, presence or absence of liver steatosis and in transplantation whether the donor organ has been retrieved from a brain dead or cardiac death donor.

4. PREVENTION and TREATMENT

There is currently no accepted treatment for liver IR injury. Several pharmacological agents and surgical techniques have been beneficial in reducing markers of hepatocyte injury in experimental liver IR, however, they are yet to show clinical benefit in human trials. The following is an outline of current and future strategies which may be effective in reducing the detrimental effects of liver IR injury in liver surgery and transplantation.

4.1 SURGICAL STRATEGIES

Inflow occlusion or portal triad clamping (PTC) can be continuous or intermittent; alternating between short periods of inflow occlusion and reperfusion. Intermittent clamping (IC) increases parenchymal tolerance to ischaemia. Hence, prolonged continuous inflow occlusion rather than short intermittent periods results in greater degree of post-operative liver dysfunction. IC permits longer total ischaemia times for more complex resections. Alternating between 15 min of inflow occlusion and 5 min reperfusion cycles can be performed safely for up to 120 min total ischaemia time. There is a potential risk of increased blood loss during the periods of no inflow occlusion. However, these intervals provide an opportunity for the surgeon to check for haemostasis and control small bleeding areas from the cut surface of the liver. The optimal IC cycle times are not clear, although intermittent cycles of up to 30 min inflow occlusion have also been reported with no increase in morbidity, blood loss or liver dysfunction compared to 15 min cycles. IC is particularly beneficial in reducing post-operative liver dysfunction in patients with liver cirrhosis or steatosis.

In liver surgery, IPC ( Ischaemic Preconditioning) involves a short period of ischaemia (10 min) and reperfusion (10 min) intraoperatively by portal triad clamping prior to parenchymal transection during which a longer continuous inflow occlusion is applied to minimise blood loss. It allows continuous ischaemia times of up to 40 min without significant liver dysfunction. However, the protective effect of IPC decreases with increasing age above 60 years old and compared to IC it is less effective in steatotic livers. Moreover, IPC may impair liver regeneration capacity and may not be tolerated by the small remnant liver in those with more complex and extensive liver resections increasing the risk of post-operative hepatic insufficiency.

In order to avoid direct ischaemic insult to the liver by inflow occlusion, remote ischaemic preconditioning (RIPC) has been used. RIPC involves preconditioning a remote organ prior to ischaemia of the target organ. It has been shown to be reduce warm IR injury to the liver in experimental studies. A recent pilot randomised trial of RIPC in patients undergoing major liver resection for colorectal liver metastasis used a tourniquet applied to the right thigh with 10 min cycles of inflation-deflation to induce IR injury to the leg for 60 min. This was performed after general anaesthesia prior to skin incision. A reduction in post-operative transaminases and improved liver function was shown without the use of liver inflow occlusion. These results are promising but require validation in a larger trial addressing clinical outcomes.

5. FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Hepatic IR injury remains the main cause of morbidity and mortality in liver surgery and transplantation. Despite over two decades of research in this area, therapeutic options to treat or prevent liver IR are limited. This is primarily due to the difficulties in translation of promising agents into human clinical studies. Recent advances in our understanding of the immunological responses and endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of liver IR injury may pave the way for the development of new and more effective and targeted pharmacological agents.

Surgery for Breast Cancer Liver Metastases

Liver resection offers the only chance of cure in patients with a variety of primary and secondary liver tumors. For breast cancer, the natural history of this condition is poorly defined and the management remains controversial. Most physicians view liver metastases from breast cancer with resignation or attempt palliation with hormones and chemotherapy. Proper patient selection is crucial to ensure favorable long-term results. Although results of hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer have been reported extensively, the experience with liver resection of metastases from breast cancer is limited. In 1991, the first series reporting hepatectomy for breast cancer patients was published.

A large series by Adam et al. reported the experience of 41 French centers regarding liver resection for noncolorectal, nonendocrine liver metastases. Among the 1452 patients who were studied, 454 (32%) were breast cancer patients. Mean age was 52 years (range 27–80 years). Most patients received adjuvant chemotherapy (58%), as few were downstaged by neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Delay between the treatment of the primary breast tumor and metastases was 54 months, with metachronous metastases in more than 90% of cases. There was a single metastasis in 56% of cases and less than three metastases in 84%. Only 8% were nonresectable. Most patients (77% of cases) underwent anatomical major resections (>3 segments). Negative margins were obtained in 82% of cases. Operative mortality was 0.2% during the 2 months following surgery. Fewer than 10% of the patients developed a local or systemic complication. With a median follow-up of 31 months, the overall survival was 41% at 5 years and 22% at 10 years, with a median of 45 months. Five- and 10-year recurrencefree survival rates were 14% and 10%, respectively.

Poor survival was associated with four factors determined by multivariate analysis: time to metastases, extrahepatic location, progression under chemotherapy treatment, and incomplete resection. At the UTMDACC, breast cancer patients who present with isolated synchronous liver metastases are treated initially with systemic chemotherapy. In responders,

hepatic resection is only contemplated if no other disease becomes evident during initial systemic treatment. Most candidates for hepatic resection undergo treatment for metachronous disease and only undergo resection for metastatic disease confined to the liver.

Principles of Surgical Resection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

There has been significant improvement in the perioperative results following liver resection, mainly due to techniques that help reduce blood loss during the operation. Extent of liver resection required in HCC for optimal oncologic results is still controversial. On this basis, the rationale for anatomically removing the entire segment or lobe bearing the tumor, would be to remove undetectable tumor metastases along with the primary tumor.

SIZE OF TUMOR VERSUS TUMOR FREE-MARGIN

Several retrospective studies and meta-analyses have shown that anatomical resections are safe in patients with HCC and liver dysfunction, and may offer a survival benefit. It should be noted, that most studies are biased, as non-anatomical resections are more commonly performed in patients with more advanced liver disease, which affects both recurrence and survival. It therefore remains unclear whether anatomical resections have a true long-term survival benefit in patients with HCC. Some authors have suggested that anatomical resections may provide a survival benefit in tumors between 2 and 5 cm. The rational is that smaller tumors rarely involve portal structures, and in larger tumors presence of macrovascular invasion and satellite nodules would offset the effect of aggressive surgical approach. Another important predictor of local recurrence is margin status. Generally, a tumor-free margin of 1 cm is considered necessary for optimal oncologic results. A prospective randomized trial on 169 patients with solitary HCC demonstrated that a resection margin aiming at 2 cm, safely decreased recurrence rate and improved long-term survival, when compared to a resection margin aiming at 1 cm. Therefore, wide resection margins of 2 cm is recommended, provided patient safety is not compromised.

THECNICAL ASPECTS

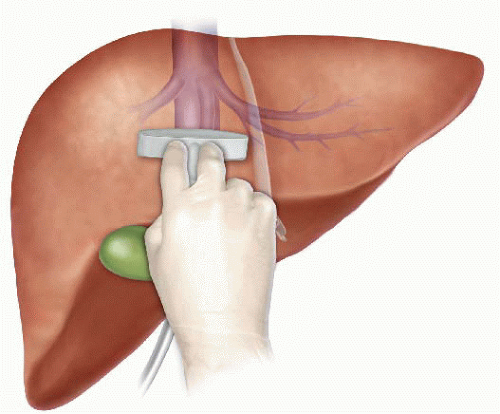

Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) is an extremely important tool when performing liver resections, specifically for patients with HCC and compromised liver function. IOUS allows for localization of the primary tumor, detection of additional tumors, satellite nodules, tumor thrombus, and define relationship with bilio-vascular structures within the liver. Finally, intraoperative US-guided injection of dye, such as methylene-blue, to portal branches can clearly define the margins of the segment supplied by the portal branch and facilitate safe anatomical resection.

The anterior approach to liver resection is a technique aimed at limiting tumor manipulation to avoid tumoral dissemination, decrease potential for blood loss caused by avulsion of hepatic veins, and decrease ischemia of the remnant liver caused by rotation of the hepatoduodenal ligament. This technique is described for large HCCs located in the right lobe, and was shown in a prospective, randomized trial to reduce frequency of massive bleeding, number of patients requiring blood transfusions, and improve overall survival in this setting. This approach can be challenging, and can be facilitated by the use of the hanging maneuver.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that blood loss and blood transfusion administration are significantly associated with both short-term perioperative, and long-term oncological results in patients undergoing resection for HCC. This has led surgeons to focus on limiting operative blood loss as a major objective in liver resection. Transfusion rates of <20 % are expected in most experienced liver surgery centers. Inflow occlusion, by the use of the Pringle Maneuver represents the most commonly performed method to limit blood loss. Cirrhotic patients can tolerate total clamping time of up to 90 min, and the benefit of reduced blood loss outweighs the risks of inflow occlusion, as long as ischemia periods of 15 min are separated by at least 5 min of reperfusion. Total ischemia time of above 120 min may be associated with postoperative liver dysfunction. Additional techniques aimed at reducing blood loss include total vascular isolation, by occluding the inferior vena cava (IVC) above and below the liver, however, the hemodynamic results of IVC occlusion may be significant, and this technique has a role mainly in tumors that are adjacent to the IVC or hepatic veins.

Anesthesiologists need to assure central venous pressure is low (below 5 mmHg) by limiting fluid administration, and use of diuretics, even at the expense 470 N. Lubezky et al. of low systemic pressure and use of inotropes. After completion of the resection, large amount of crystalloids can be administered to replenish losses during parenchymal dissection.

LAPAROSCOPIC RESECTIONS

Laparoscopic liver resections were shown to provide benefits of reduced surgical trauma, including a reduction in postoperative pain, incision-related morbidity, and shorten hospital stay. Some studies have demonstrated reduced operative bleeding with laparoscopy, attributed to the increased intra-abdominal pressure which reduces bleeding from the low-pressured hepatic veins. Additional potential benefits include a decrease in postoperative ascites and ascites-related wound complications, and fewer postoperative adhesions, which may be important in patients undergoing salvage liver transplantation. There has been a delay with the use of laparoscopy in the setting of liver cirrhosis, due to difficulties with hemostasis in the resection planes, and concerns for possible reduction of portal flow secondary to increased intraabdominal pressure. However, several recent studies have suggested that laparoscopic resection of HCC in patients with cirrhosis is safe and provides improved outcomes when compared to open resections.

Resections of small HCCs in anterior or left lateral segments are most amenable for laparoscopic resections. Larger resections, and resection of posterior-sector tumors are more challenging and should only be performed by very experienced surgeons. Long-term oncological outcomes of laparoscopic resections was shown to be equivalent to open resections on retrospective studies , but prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings. In recent years, robotic-assisted liver resections are being explored. Feasibility and safety of robotic-assisted surgery for HCC has been demonstrated in small non-randomized studies, but more experience is needed, and long-term oncologic results need to be studied, before widespread use of this technique will be recommended.

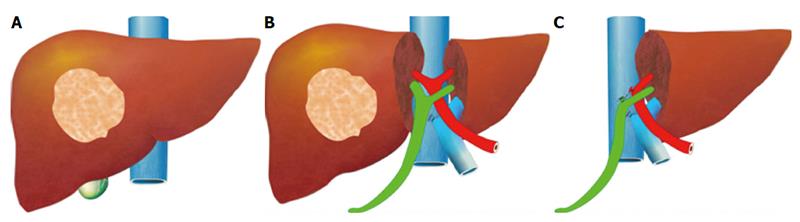

ALPPS: Associating Liver Partition with Portal vein ligation for Staged hepatectomy

The pre-operative options for inducing atrophy of the resected part and hypertrophy of the FLR, mainly PVE, were described earlier. Associating Liver Partition with Portal vein ligation for Staged hepatectomy (ALPPS) is another surgical option aimed to induce rapid hypertrophy of the FLR in patients with HCC. This technique involves a 2-stage procedure. In the first stage splitting of the liver along the resection plane and ligation of the portal vein is performed, and in the second stage, performed at least 2 weeks following the first stage, completion of the resection is performed. Patient safety is a major concern, and some studies have reported increased morbidity and mortality with the procedure. Few reports exist of this procedure in the setting of liver cirrhosis. Currently, the role of ALPPS in the setting of HCC and liver dysfunction needs to be better delineated before more widespread use is recommended.

Pringle Maneuver

After the first major hepatic resection, a left hepatic resection, carried out in 1888 by Carl Langenbuch, it took another 20 years before the first right hepatectomy was described by Walter Wendel in 1911. Three years before, in 1908, Hogarth Pringle provided the first description of a technique of vascular control, the portal triad clamping, nowadays known as the Pringle maneuver. Liver surgery has progressed rapidly since then. Modern surgical concepts and techniques, together with advances in anesthesiological care, intensive care medicine, perioperative imaging, and interventional radiology, together with multimodal oncological concepts, have resulted in fundamental changes. Perioperative outcome has improved significantly, and even major hepatic resections can be performed with morbidity and mortality rates of less than 45% and 4% respectively in highvolume liver surgery centers. Many liver surgeries performed routinely in specialized centers today were considered to be high-risk or nonresectable by most surgeons less than 1–2 decades ago.Interestingly, operative blood loss remains the most important predictor of postoperative morbidity and mortality, and therefore vascular control remains one of the most important aspects in liver surgery.

“Bleeding control is achieved by vascular control and optimized and careful parenchymal transection during liver surgery, and these two concepts are cross-linked.”

First described by Pringle in 1908, it has proven effective in decreasing haemorrhage during the resection of the liver tissue. It is frequently used, and it consists in temporarily occluding the hepatic artery and the portal vein, thus limiting the flow of blood into the liver, although this also results in an increased venous pressure in the mesenteric territory. Hemodynamic repercussion during the PM is rare because it only diminishes the venous return in 15% of cases. The cardiovascular system slightly increases the systemic vascular resistance as a compensatory response, thereby limiting the drop in the arterial pressure. Through the administration of crystalloids, it is possible to maintain hemodynamic stability.

In the 1990s, the PM was used continuously for 45 min and even up to an hour because the depth of the potential damage that could occur due to hepatic ischemia was not yet known. During the PM, the lack of oxygen affects all liver cells, especially Kupffer cells which represent the largest fixed macrophage mass. When these cells are deprived of oxygen, they are an endless source of production of the tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukins 1, 6, 8 and 10. IL 6 has been described as the cytokine that best correlates to postoperative complications. In order to mitigate the effects of continuous PM, intermittent clamping of the portal pedicle has been developed. This consists of occluding the pedicle for 15 min, removing the clamps for 5 min, and then starting the manoeuvre again. This intermittent passage of the hepatic tissue through ischemia and reperfusion shows the development of hepatic tolerance to the lack of oxygen with decreased cell damage. Greater ischemic tolerance to this intermittent manoeuvre increases the total time it can be used.